Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak by Charlie Jane Anders

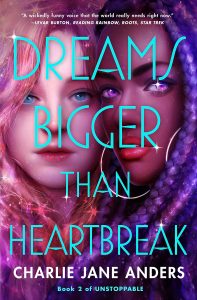

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak, Charlie Jane Anders (Tor Teen 978-1250317391, $18.99, 320pp, hc) April 2022.

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak, Charlie Jane Anders (Tor Teen 978-1250317391, $18.99, 320pp, hc) April 2022.

It’s practically an unwritten rule that middle volumes of trilogies should shade a bit darker, with higher stakes, unexpected complications, dimmer hopes, and a growing sense of desperation. If you’re going to (apparently) kill off Frodo, volume two is the place to do it. The second volume of Charlie Jane Anders’s YA Unstoppable trilogy, Dreams Bigger than Heartbreak, manages all this with considerable panache, especially in its kinetic second half, but not before it spends a fair amount of time delving more deeply into the lives and anxieties of its young protagonists. We might end up with a cosmic space opera worthy of Edmond Hamilton titles like Planets in Peril or The Sun Smasher (both titles are literalized here) but early on, the concerns are just as likely to center on who gets to room with whom or who gets to be a princess (or at least a princess contender). If Anders’s first volume, Victories Greater than Death, leaned a bit heavily on classic SF-style geek valorization, with brilliant misfit kids from all over the world joining a starship crew of the Royal Fleet, Dreams Bigger than Heartbreak develops them into more compelling and conflicted characters who have learned to confront loss and rejection as well as to pull off hairbreadth escapes and brilliant last-minute improvisations.

We again meet the crew of mostly human young people from the first volume – Tina, actually the clone of legendary space captain Thaoh Argentian; her best friend Rachael, a preternaturally talented artist; Rachael’s boyfriend Yiwei, both a musician and a roboticist; the Brazilian hacker Elza; the brilliant gamer from Mumbai, Damini; the British prodigy Kez; and a few helpful aliens like the courageous Yatto the Monntha. But while Tina was the narrator and central character there, here the focus shifts largely to Rachael – who, having managed to save everyone by using the artistic centers of her brain to control an ancient superweapon, has entirely lost her ability to make art – and to Elza, who is now Tina’s girlfriend and who is a candidate to become a princess (although we soon learn that this means something more than it seems). The villain Marrant is also back, smirky and garrulous as ever, though now we’re given a humanizing backstory that doesn’t come close to redeeming him, as well as a new antagonist in Kankakn, founder and self-proclaimed spiritual leader of the ironically named militaristic movement the Compassion, which is at war with the Royal Fleet. The Compassion has legally gained control of an entire planet, through a racist and xenophobic campaign that rings some very familiar bells in our own recent history, and trying to rescue refugees is only one of the challenges facing our heroes.

Dreams Bigger than Heartbreak introduces a few new characters as well, the most interesting of whom is the mysterious Nyitha, who tries to help Rachael rediscover her artistic gifts and who has a complex backstory of her own. The space opera aspects of the plot basically do what space opera is supposed to do, ever widening the scope of potential disaster and repeatedly placing our pals in apparently inescapable peril, including a few fairly graphic space-horror scenarios. This time it has something to do with the Vayt, the ancient ‘‘Shapers’’ who are now awake and are terrified of something far worse than themselves, called the Bereavement. We do get a glimpse of what that actually means, but mostly Anders has left herself an opening for a galactic-scale final act. As much unhinged fun as that promises to be, the emotional core of the Unstoppable series still rests with these increasingly complicated kids, who are actually far more compelling than the sometimes cartoonish roles they find themselves thrust into, and who are in for some serious therapy if they ever make it back to Earth.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the February 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.