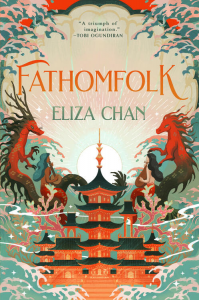

Liz Bourke Reviews Fathomfolk by Eliza Chan

Fathomfolk, Eliza Chan (Orbit US 978-0-316-56492-2, $19.99, 448pp, tp) February 2024. Cover by Kelly Chang.

Fathomfolk, Eliza Chan (Orbit US 978-0-316-56492-2, $19.99, 448pp, tp) February 2024. Cover by Kelly Chang.

Eliza Chan has racked up several short fiction publications in recent years, but Fathomfolk represents her debut novel. And it is an interesting debut, albeit one that, on the whole, didn’t come together as I might have hoped.

Fathomfolk takes place in a world dominated by water, apparently in the aftermath of a process that caused water levels to rise. Tiankawi, the city where most of its action is set, has practically no dry land at all. It’s a city whose foundations are water, and one where the human inhabitants engage in the awkward xenophobia of restricting the movements and rights of the immigrant sea people – the titular fathomfolk – on whom, it seems, what passes for the city’s economy relies.

The fathomfolk are a diverse array of sea-dwelling beings, many of whom are recognisable from our mythological, folkloric, or storytelling traditions: sirens and kelpies, shapeshifting royal water dragons and sea-witches. Their underwater kingdoms, the havens, are being threatened and destroyed by ecological damage and pollution from (apparently) human sources, and even with the magic of their water-weaving, they do not seem to be able to match human technology.

Though some fathomfolk have lived in Tiankawi for generations and intermarried – at least low down the class scale – with humans, further immigration into Tiankawi is tightly controlled, with restrictive visas and a requirement for all fathomfolk to be fitted with a pakalot, a device that prevents them from using water-weaving against humans. Desperate fathomfolk still try to smuggle themselves into the city, some of them dying – as desperate refugees regularly do in our own world – in the process.

Very few fathomfolk are free of the pakalot. One of them is Mira, part-siren, part-human, who has fought her way to the senior post of captain of the border guard by dint of being both very good at her job and a poster child for ‘‘diversity.’’ It probably doesn’t hurt that her lover is Kai, a shapeshifting royal dragon and the official ambassador from the nearest fathomfolk kingdom – whose allegiances come across as rather complicated, since he also holds the post of Tiankawi’s Minister of Fathomfolk. He, too, is free of the pakalot. As is, it seems, the amoral sea-witch Cordelia, who lives one life making deals and running organised crime among the fathomfolk, and another in her shapeshifted human form as Serena, ambitious wife of the minister in charge of Tiankawi’s police force and mother to his children.

When Nami, Kai’s younger sister, is exiled to Tiankawi for an ill-thought-out act of radicalism, she falls in with Tiankawi’s own band of revolutionary agitators, the Drawbacks. The Drawbacks want to overturn Tiankawi’s discriminatory system entirely, burn – or drown – the city entirely if necessary, unlike more moderate voices working for change within the system. Kai and Mira are our representatives of those more moderate voices, and the incremental change that they’re currently working for is to relax the pakalot restrictions in order to allow the fathomfolk to use water-weaving in self-defence.

In Tiankawi, Chan gives us a richly realised city, with all the trappings of modernity in its trams and fancy restaurants, electricity and elevators, and one with a starkly recognisable division between the haves at the city’s literal centre and the have-nots relegated to its polluted margins. The city is also literally powered by the exploitation of this permanent underclass of immigrants and their descendants: Fathomfolk with no other employment (of whom there are many) take shifts working at the engine that generates electricity for most of Tiankawi. That engine works by siphoning the power of their water-weaving out through the pakalot that restrains them.

But Fathomfolk’s narrative and its pacing didn’t quite work for me. (Bear with me here.) Fathomfolk is told primarily from the points of view of Mira, Nami, and Cordelia, who all have different perspectives on the city and its communities. They exemplify very recognisable character types, when it comes to characters from marginalised communities: the honest and straightforward professional who’s fighting the odds to succeed in a prejudiced career, in this case the police force, before finally being scapegoated because her competence – her decisions, her very existence – embarrasses her superiors (Mira); the closeted or passing individual who has built a second life in which she must hide and deny her first one in a search for security and power, but who finds the second life becoming a trap (Cordelia); and the former privileged kid swept up into emotive radicalism when she encounters discrimination, encouraged into participating in violent direct actions without fully grasping their consequences or the strategic aims of the revolutionaries she’s fallen in with (Nami). Their familiarity as character types makes them in many respects predictable, though Chan does interesting things in developing Mira’s relationship with Nami and Nami’s quasi-filial relationship with Mira’s own mother. Cordelia, however, at times veers perilously close to the cliché of an amoral woman manipulating (or attempting to manipulate) everyone around her to satisfy her own ambition. Her goals appear to be largely selfish, so that instead of a neutral depiction of someone choosing to (try to) pass in a discriminatory society, she acts instead as an antagonist to the other, less self-interested, characters. (The narrative even undercuts her cleverness in fooling the upper-crust world: it turns out someone close to her has known the entire time, and has gone along so long as it suited that person’s ambitions.)

I don’t object to the use of Mira as a lens to examine how Tiankawi fails and exploits even those fathomfolk most committed to working within its structures to achieve minimal reform, or how the fathomfolk community is not a singular unity (and has members who exploit each other), but I would have preferred it if her viewpoint offered more of a a window into Tiankawi’s politics and political structures. We’re a sixth of the way through the book before we understand that Kai, who she’s dating, is Minister for Fathomfolk; longer before it becomes plain that she and Kai are attempting to persuade the other ministers of Tiankawi to pass a law allowing for fathomfolk self-defence. The existence of a generator powering the city that siphons the power of water-weaving out of fathomfolk comes as a shocking reveal for Nami more than halfway through the novel, because while everyone knows where the city’s electricity comes from, no one has told her. Or, for that matter, has told the reader. As a revelation, for me, it’s not particularly shocking, whereas the visible presence of this very literal form of exploitation from earlier in the novel might well have allowed for a more joined-up development of Mira’s and Nami’s respective narrative arcs, as well as their evolving positions vis-a-vis Tiankawi’s xenophobic and exclusionary hierarchies.

This is a novel whose thematic centre is the experience of a marginalised, surveilled, and strongly policed community, and the strain that this experience puts on the community as a whole and individuals within it; a thematic argument about the relative value of pushing for incremental, moderate reform and the violent satisfaction of revolutionary change. It is impossible to read it and not find immediate and painful parallels with marginalised communities in our real world. Chan’s parallels to the real world, of course, extend beyond the obvious one to the experience of immigrants and refugees who are violently denied entry to (or offered only very conditional residence in) the same nations whose political and economic leadership class are responsible (in whole or in part) for making those refugees’ countries of origin places where it is difficult to make lives at all, much less good ones, but one feels that Chan has been particularly inspired by Fortress Europe and the UK administration since 2010.

The fathomfolk immigrants of Tiankawi are presented as a dangerous, less-than-human other, much as our own anti-immigration rhetorics seeks to cast, for example, the refugees who try to cross the Mediterranean in overcrowded fishing-boats as existential threats to an EU government’s balance sheet and their citizens’ ‘‘way of life.’’ And yet, unlike refugees and immigrants in our own world, the fathomfolk of Tiankawi have an intrinsic power that Tiankawi’s human elites do not, in the form of their ability to water-weave and the various magical talents that come along with their ability to breathe underwater. Tiankawi’s elite shackle and restrain this power, exploit it to their own ends – but there’s no doubt that it is power, and power with inarguably transformative potential. Indeed, the transformative potential of this power is realised in the novel’s climax.

At times Fathomfolk can feel a little scrappy and disjointed, rushing headlong from confrontational incident to shocking revelation. But Chan writes with the kind of energy that makes the helter-skelter nonetheless entertaining, and her willingness to grapple with substantial and (painfully, eternally) topically relevant themes gives weight to the lives and struggles of her characters. On the whole, Fathomfolk is a promising debut. It doesn’t quite come together as more than the sum of its parts, but I definitely still enjoyed it. I’ll be looking for Chan’s future work with interest.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the December and January 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.