The Year in Review 2023 by Russell Letson

(2022)

Long Games, Nightmares, and Retrospectives by Russell Letson

I look into the tea leaves – well, the coffee grounds – at the bottom of the year’s cup and find no wisdom or insight into either the state of the field or even my own reading patterns. As usual. Nevertheless, I am more than content with where my nose-following and stumbling around in the dark have taken me in 2023, across territories much like those I visited in 2022. (I’m even recycling part of the maps/territories metaphor from last year’s overview essay, though now I am discarding any pretense of mapping. What follows is just a ramble.)

Two writers continue to tempt me back into reading fantasy, perhaps because they both resist any hint of coziness. Such uneasy atmospherics have been at the heart of Charles Stross’s Laundry stories from the start, and Season of Skulls, third book in the subseries that began with Dead Lies Dreaming, extends the reach of the Laundryverse dystopian nightmare into the past – or, to be precise, a past, a Regency-romance alternate-history ‘‘pocket universe’’ that mixes real-history socio-economic-gender-inequality ugliness with the expected supernatural menaces, eldritch terrors, and psychopathologies, with an added dash of intrigue-adventure – in this case, the 1960s television series The Prisoner. Adrian Tchaikovsky also likes to mix and match genre features and motifs in the course of a single series (now identified as The Tyrant Philosophers). House of Open Wounds takes place in the same magic-saturated otherworld as The City of Last Chances, but where the first book is a magic- and intrigue-driven McGuffin-hunt climaxing in an urban rebellion, the second is a bleak and bloody view of warfare seen from the viewpoint of the operators of a field hospital. Like Stross, Tchaikovsky leavens it all with dark, ironic humor, but that’s just powdered sugar on some bitter bread indeed. And both writers manage to leave me somehow not-despairing, though I’m still not sure why.

Two writers continue to tempt me back into reading fantasy, perhaps because they both resist any hint of coziness. Such uneasy atmospherics have been at the heart of Charles Stross’s Laundry stories from the start, and Season of Skulls, third book in the subseries that began with Dead Lies Dreaming, extends the reach of the Laundryverse dystopian nightmare into the past – or, to be precise, a past, a Regency-romance alternate-history ‘‘pocket universe’’ that mixes real-history socio-economic-gender-inequality ugliness with the expected supernatural menaces, eldritch terrors, and psychopathologies, with an added dash of intrigue-adventure – in this case, the 1960s television series The Prisoner. Adrian Tchaikovsky also likes to mix and match genre features and motifs in the course of a single series (now identified as The Tyrant Philosophers). House of Open Wounds takes place in the same magic-saturated otherworld as The City of Last Chances, but where the first book is a magic- and intrigue-driven McGuffin-hunt climaxing in an urban rebellion, the second is a bleak and bloody view of warfare seen from the viewpoint of the operators of a field hospital. Like Stross, Tchaikovsky leavens it all with dark, ironic humor, but that’s just powdered sugar on some bitter bread indeed. And both writers manage to leave me somehow not-despairing, though I’m still not sure why.

On the other sides of various genre divides, recognizable and unmistakable science fiction continues to flourish. Much of this comes from writers I have long followed and who never disappoint. Thirty years ago next month, I reviewed the first of the Foreigner novels, now bylined by C.J. Cherryh & Jane Fancher, and with number 22, Defiance, the series has passed Patrick O’Brian’s 21-volume Aubrey-Maturin cycle, with which it shares several virtues, notably central characters with interestingly complex internal lives, inhabiting an immersive and challenging world that can push back hard. The longer the series continues, the deeper and more detailed the history of the nonhuman atevi culture and the view of atevi psychology become – while still delivering the intrigue and climactic encounters that are the equivalents of Maturin’s espionage activities and Aubrey’s sea battles.

On the other sides of various genre divides, recognizable and unmistakable science fiction continues to flourish. Much of this comes from writers I have long followed and who never disappoint. Thirty years ago next month, I reviewed the first of the Foreigner novels, now bylined by C.J. Cherryh & Jane Fancher, and with number 22, Defiance, the series has passed Patrick O’Brian’s 21-volume Aubrey-Maturin cycle, with which it shares several virtues, notably central characters with interestingly complex internal lives, inhabiting an immersive and challenging world that can push back hard. The longer the series continues, the deeper and more detailed the history of the nonhuman atevi culture and the view of atevi psychology become – while still delivering the intrigue and climactic encounters that are the equivalents of Maturin’s espionage activities and Aubrey’s sea battles.

I have been reviewing Jack McDevitt for almost as long as the Foreigner series, though only through 17 novels, mostly divided between two series. Village in the Sky belongs to the Alex Benedict cycle, in which the future-antiquities dealer delves into the mysteries of history, human and cosmic, including the Big Question of whether there are more than two intelligent species in the galaxy. The answer finally delivered in Village nearly inverts the Foreigner motif that nonhuman Others are likely to be, well, psychologically Other. When the aliens come bearing their favorite plays and self-help books, McDevitt seems to be suggesting that no matter where you go, there you are, even 9000 years in the future and halfway across the galaxy.

Then there’s SF that makes Cherryh & Fancher and McDevitt, for all their interstellar travel and alien contacts, seem cozy. Stephen Baxter’s Creation Node locates merely interplanetary factions and tensions in a context of chilly multiversal realities and opaque, godlike powers, emphasizing the kind of vast-scale vision that SF inherited from Olaf Stapledon. Neal Asher’s Polity universe depends on that kind of spatial and temporal vastness to back up its space operatics, but War Bodies occupies just one corner of this setting: two planets and two military campaigns. What it lacks in Imax scope it makes up for in the intensity of its warfare and its relentless examination of the costs of total war. Lords of Uncreation, the finale of Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Final Architecture series, also depends on the collision of space opera and cosmology opera, along with a dash of the ironic nebbish-as-hero motif that runs through the Tyrant Philosophers books.

Then there’s SF that makes Cherryh & Fancher and McDevitt, for all their interstellar travel and alien contacts, seem cozy. Stephen Baxter’s Creation Node locates merely interplanetary factions and tensions in a context of chilly multiversal realities and opaque, godlike powers, emphasizing the kind of vast-scale vision that SF inherited from Olaf Stapledon. Neal Asher’s Polity universe depends on that kind of spatial and temporal vastness to back up its space operatics, but War Bodies occupies just one corner of this setting: two planets and two military campaigns. What it lacks in Imax scope it makes up for in the intensity of its warfare and its relentless examination of the costs of total war. Lords of Uncreation, the finale of Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Final Architecture series, also depends on the collision of space opera and cosmology opera, along with a dash of the ironic nebbish-as-hero motif that runs through the Tyrant Philosophers books.

There’s life beyond space operatics. Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch world accommodates smaller-scale stories, especially when it escapes Radchaai space, as in Translation State, which focuses on matters of identity and authenticity and belonging, with a very large dollop of alien-viewpoint strangeness and sideways glimpses of the larger universe outside the story’s immediate confines. Arkady Martine’s Rose/House also offers a contrast to the far-future, intrigues-and-spacewar setting of her Teixcalaan Empire novels. Instead of imperial courts and starship warfleets, the novella is a chamber work, a murder mystery partly set in the confines of a creepy, cybernetically haunted house that offers a flavor of strangeness quite distinct from the clash-of-cultures tensions of her earlier books.

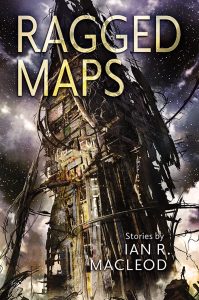

If it’s challenging to keep up with the flood of novels, I find it impossible to even attempt to track short fiction, but concentrated doses of individual writers serve to remind me of how crucial to the field the short form is, a place where writers get to stretch out in an environment quite different from that of book publishing. So single-author collections, especially from writers whose novels I have followed, are a welcome change of pace. Subterranean Press is particularly good at assembling substantial periodic reports and career overviews, often enhanced by authorial notes and comments. Ian R. MacLeod’s Ragged Maps is of the periodic-report sort, focusing on 2016-22, while The Best of Michael Swanwick, Volume Two is what it says on the cover, 23 years worth of production. Both volumes do what these collections do best: reveal the writers’ range of idea and effect and affect, concentrated at less-than-novel length.

If it’s challenging to keep up with the flood of novels, I find it impossible to even attempt to track short fiction, but concentrated doses of individual writers serve to remind me of how crucial to the field the short form is, a place where writers get to stretch out in an environment quite different from that of book publishing. So single-author collections, especially from writers whose novels I have followed, are a welcome change of pace. Subterranean Press is particularly good at assembling substantial periodic reports and career overviews, often enhanced by authorial notes and comments. Ian R. MacLeod’s Ragged Maps is of the periodic-report sort, focusing on 2016-22, while The Best of Michael Swanwick, Volume Two is what it says on the cover, 23 years worth of production. Both volumes do what these collections do best: reveal the writers’ range of idea and effect and affect, concentrated at less-than-novel length.

Greg Egan and Neal Asher issue fairly regular reports of what they’re up to in the form of periodic collections. Egan’s Sleep and the Soul covers just three years’ output but reveals the consistency of his longtime thematic interests (the nature and operations of consciousness, the unpicking of ethical-moral issues, hard-SF thinking applied to very exotic imaginary environments) and his unflagging attachment to reason. Asher’s Lockdown Tales II is something of a writer’s-journal product, the second volume of short fiction produced during Covid-dictated restrictions on other activities. These stories also reveal the writer’s persistent concerns and story patterns (predation, monsters, conflict) and are particularly interesting when set next to War Bodies, presumably composed in the same period.

Greg Egan and Neal Asher issue fairly regular reports of what they’re up to in the form of periodic collections. Egan’s Sleep and the Soul covers just three years’ output but reveals the consistency of his longtime thematic interests (the nature and operations of consciousness, the unpicking of ethical-moral issues, hard-SF thinking applied to very exotic imaginary environments) and his unflagging attachment to reason. Asher’s Lockdown Tales II is something of a writer’s-journal product, the second volume of short fiction produced during Covid-dictated restrictions on other activities. These stories also reveal the writer’s persistent concerns and story patterns (predation, monsters, conflict) and are particularly interesting when set next to War Bodies, presumably composed in the same period.

Once again my particular reading history doesn’t reveal any secret wisdom about the state of the field, except that it continues to generate more strong work than I could ever keep up with, and writers continue to find ways of reshaping and recombining long-recognized raw materials into configurations that make me want to keep reading.

Particularly Recommended:

Defiance, C. J. Cherryh & Jane S. Fancher

Translation State, Ann Leckie

Ragged Maps, Ian R. MacLeod

The Best of Michael Swanwick, Volume Two, Michael Swanwick

House of Open Wounds, Adrian Tchaikovsky

This review and more like it in the February 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.