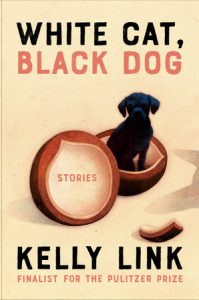

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews White Cat, Black Dog by Kelly Link

White Cat, Black Dog, Kelly Link (Random House 978-0-59344-995-0, $27.00, 272pp, hc) March 2023.

White Cat, Black Dog, Kelly Link (Random House 978-0-59344-995-0, $27.00, 272pp, hc) March 2023.

There are a lot of things you can do with fairy tales, but leaving them alone doesn’t seem to be one of them. Even the Brothers Grimm themselves messed around with the stories they collected, and various redactions, reinterpretations, satires, and improvisations have been with us pretty much as long as the tales themselves. Kelly Link has also visited this territory before (“Travels with the Snow Queen”, “Shoe and Marriage”, “Catskin”), but White Cat, Black Dog is her first collection devoted to stories derived from specific fairy tale sources (though none of those three stories are included, nor are any stories which were included in earlier Link collections). Link’s approach to her materials in these seven stories is less like that of Jane Yolen (whose recent How to Fracture a Fairy Tale often sought to unpack the source tales in specific cultural contexts) and more like that of Angela Carter, whose classic 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories tended to treat the originals more like starting points for her own dark fantasias. Link helpfully offers parenthetical subtitles giving each source tale, which sometimes lends the collection a playful Where’s-Waldo tone, inviting us to spot the original, which may show up as an embedded tale-within-a-tale or be subject to a complete reimagining, but is never anything as simple as metaphor or apologue. Shaun Tan’s characteristically mysterious and evocative illustrations add to this tone.

“The Girl Who Did Not Know Fear”, for example, begins as a familiar and all too credible travel nightmare: a well-known professor, anxious to return to her wife and daughter after being celebrated at a conference, gets caught up in seemingly endless flight delays while spending nights in bleak hotels. Only when she finally catches a flight and begins chatting with her seatmates does she hear about the girl of the title, who was oblivious to the ghosts in her haunted apartment. But by then we’ve started making our own connections between Link’s basically realistic tale and the world of fable. Similarly, “Prince Hat Underground” begins as a fairly domestic mystery when Prince Hat simply walks off one day with a strange woman, leaving his husband Gary to set out on a quest that even takes him to hell – but not until toward the end do we find a version of the source tale, “East of the Sun, West of the Moon”. At times, Link can yank us between worlds in a single sentence. “Skinder’s Veil”, which may be my favorite story in the collection (and another that features an academic protagonist), begins with the formula “Once upon a time” followed by “there was a graduate student in the summer of his fourth year who had not finished his dissertation” – hardly the stuff of fairy tales, we might think – until it is. Such are the polarities that define many of these tales. That grad student agrees to fill in as a substitute housesitter in a spooky home whose owner has imposed strange rules: if he himself shows up, he’s not to be admitted, but anyone showing up at the back door should be allowed in. The tale eventually turns out to be a derivation of “Snow White and Rose Red”, but with uniquely Link-esque twists, most notably the neat ending.

While fairy tales provide a thematic throughline in the collection, a couple of the stories draw equally on SF tropes. Probably the most familiar story is “The Game of Smash and Recovery”, which showed up in no fewer than four year’s best anthologies and earned a Sturgeon Award. With its title’s vague evocation of Cordwainer Smith and its dedication to Iain M. Banks, it reimagines Hansel and Gretel as Anat and Oscar, alone on a hazardous planet called Home while their parents are delayed on a trip, assisted by “Handmaids” and threatened by “vampires,” though of course nothing is quite as it first seems. “The White Road” features a traveling company making their way through the ruins of a world transformed by unspecified disasters that led to the appearance of “white roads”, which might shift or disappear without notice, and whose travelers are fearsome. The company is on its way to Bremen, a pretty clear hint as to the source fairy tale, but the setup suggests a far more surreal and psychically disturbing version of the familiar postapocalyptic scenario of Station Eleven and other tales.

No such collection would be complete without animal tales, though Link’s examples are both from sources other than Grimm. “The White Cat’s Divorce” most clearly follows its literary source, Countess d’Aulnoy’s “The White Cat”. Instead of a king, though, Link presents us with a comically self-absorbed, preposterously wealthy, and all too familiar father, who sets ridiculous tasks for his three sons as a kind of loyalty test to determine who will be his sole heir. The youngest son finds himself stranded in a remote cannabis farm staffed entirely by cats, and the white cat of the title turns out to be an importantly tutelary figure, as in d’Aulnoy’s original. “The Lady and the Fox” is a much looser and more transformed version of “Tam Lin”, which follows the life of the goddaughter of a wealthy and somewhat decadent family, who over the years finds herself falling in love with a ghostlike figure in archaic dress who occasionally visits the family home and is only seen by her. Both tales combine a trenchant satirical view of privilege and class with a celebration of the disruptive power of magic, and those unexpected disruptions are a key feature of what makes a Link story unique. White Cat, Black Dog may be the most thematically unified of Link’s collections so far, but as always each story remains a delightful surprise, leaving us where we never quite expected to be.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the February 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.