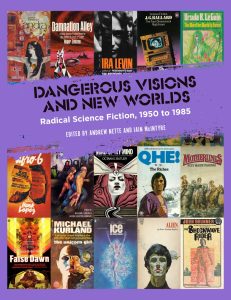

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro Reviews Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985 by Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, eds

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985, Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, eds. (PM Press 978-1629639321, $59.95, 224pp, hc) October 2021.

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985, Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre, eds. (PM Press 978-1629639321, $59.95, 224pp, hc) October 2021.

The Melbourne-based duo of writers/editors Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre follow up their two previous PM Press volumes, Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (2017) and Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 (2019), with a brand-new tome on ‘‘radical science fiction’’ published mostly during what, in their Introduction, they term the ‘‘long sixties,’’ a period stretching from the late 1950s through the 1970s. Readers conversant with genre history will be familiar with the salient movement of this period, called the New Wave, and the forms of expression it helped to usher into the genre, both in terms of content and modernist techniques, but even those readers should find plenty of value here. Nette & McIntyre’s approach parallels the editorial directive of Desirina Boskovich’s recent Lost Transmissions: The Secret History of Science Fiction and Fantasy (2019): a collection of subject-specific essays by a variety of writers and scholars, with additional interstitial entries contributed by the editors themselves. In their Introduction they mention ‘‘twenty-four chapters written by contemporary authors and critics.’’ By my reckoning, in addition to the Introduction the book contains 37 chapters, of which 20 are authored externally and 17 – eight by Nette and nine by McIntyre – are sourced in-house. All of this content, centered sometimes overtly and sometimes peripherally around the aforementioned ‘‘period of trenchant social change,’’ is interesting, and much of it is surely new to this kind of pop culture archival history. The editors’ purview is generously scoped, and the detailed treatment of UK phenomena and trends is refreshing. The editors note that ‘‘the influence of psychedelia, surrealism, and experimentation in general on book cover art during the period can arguably be seen most strongly in the science fiction field,’’ and they have included hundreds of illustrative covers that eloquently make that point. Turning to any random page proves a delicious exercise of artistic degustation, making the book double as coffee-table divertissement.

Nette & McIntyre observe that their chosen period was ‘‘most explicitly demonstrated through a host of liberatory and resistance movements focused on class, racial, gender, sexual, and other inequalities,’’ and these provide clustering themes for their material. Treatments of sex include two of my favorite essays, Rob Latham’s learned ‘‘Sextrapolation in New Wave Science Fiction’’ (a reprint) and Rebecca Baumann’s fantastic ‘‘Speculative Fuckbooks: The Brief Life of Essex House, 1968–1969’’. Latham’s piece provides an excellent list of 1950s short stories ‘‘published in the magazines that dealt explicitly with sexual topics the genre had long ignored.’’ He then proceeds to discuss ‘‘three significant, at times overlapping, ways in which SF’s new sexual openness was expressed during the late 1960s and early 1970s,’’ namely a ‘‘feminist critique of normative gender roles and sexual relationships,’’ ‘‘the proliferation of various forms of SF pornography,’’ and ‘‘non-pornographic forms of ‘sextrapolation’: projecting future trends based on current sexual mores or inventing novel sexual practices and relationships.’’ Baumann’s entry, which beautifully chronicles Milton Luros and Brian Kirby’s Essex House, expounds on the publisher’s most interesting and outré titles, such as the Agency trilogy and Brain-Plant tetralogy by David Meltzer, reflecting that they exemplify the Speculative Fuckbook subgenre: ‘‘cynical yet earnest, darkly humorous but deeply unsettling, excruciatingly pretentious yet not without charm and even moments of whimsy.’’ Also noteworthy is Baumann’s discussion of women authors, such as Alice Louise Ramirez, and ‘‘perhaps the most interesting woman writing for Essex House…. Jean Marie Stine, a transgender woman who was at the time still writing under the name Hank Stine, a variant of her then legal name.’’ Baumann concludes that ‘‘no other publisher has blended literary pretension, social criticism, pornography, and speculation in quite the same way.’’ Maitland McDonagh’s ‘‘The Stars My Destination: The Future According to Gay Adult Science Fiction Novels of the 1970s’’, Kirsten Bussière’s ‘‘Feminist Future: Time Travel in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time’’, and McIntyre’s closing ‘‘Herland: The Women’s Press and Science Fiction’’ provide additional insights into literary matters of sex and gender.

Race is foregrounded in several pieces, like McIntyre’s ‘‘Flying Saucers and Black Power: Joseph Denis Jackson’s 1967 Insurrectionist Novel The Black Commandos’’ and another highlight, Michael A. Gonzales’ ‘‘Black Star: The Life and Work of Octavia Butler.’’ I was personally tickled to discover Daniel Shank Cruz’s ‘‘‘We change – and the whole world changes’: Samuel R. Delany’s Heavenly Breakfast in Context’’, because I feel that Delany’s magnificent short memoir is sometimes overlooked in discussions of his oeuvre and should be singled out for recognition, as it is here. ‘‘Delany repeatedly highlights the potential of communes for changing society,’’ Cruz writes, ‘‘while also lamenting the lack of language available for describing communal experience.’’ This search for new ways of conveying seemingly incommunicable experiences, often of the religious or drug-induced varieties – see McIntyre’s ‘‘Flawed Ancients, New Gods, and Interstellar Missionaries: Religion in Postwar SF’’ and ‘‘Higher than a Rocket Ship: Drugs in SF’’ – led many genre writers of the day to emulate strategies from ‘‘modernist prose and poetry, William S. Burroughs and the Beats, New Journalism,’’ among others.

The book’s eponymous twin inspirations, Harlan Ellison’s epoch-defining anthology Dangerous Visions and Michael Moorcock’s revolutionary editorial reign at New Worlds, are afforded their own dedicated pieces, and though this is well-trodden ground, the recaps are nonetheless engaging and capture how much was felt to be at stake with these enterprises. Other expected heavy-hitters of the era, like J.G. Ballard, Norman Spinrad, Brian Aldiss, Joanna Russ, Thomas M. Disch, James Tiptree Jr., Ursula K. Le Guin, and Moorcock (as writer rather than editor) also get their due. Author-centric entries include Kat Clay’s ‘‘On Earth the Air Is Free: The Feminist Science Fiction of Judith Merril’’, Nick Mamatas’s ‘‘God Does, Perhaps? The Unlikely New Wave SF of R.A. Lafferty’’, Scott Adlerberg’s ‘‘A New Wave in the East: The Strugatsky Brothers and Radical Sci-fi in Soviet Russia’’, and Lucy Sussex’s ‘‘Performative Gender and SF: The Strange but True Case of Alice Sheldon and James Tiptree, Jr.’’. But there’s also coverage of writers less often discussed in the same context, like Hank Lopez, Barry Malzberg, Louise Lawrence, Ira Levin, Mack Reynolds, and Mick Farren (impressively, ‘‘Mick Faren: Fomenting the Rock Apocalypse’’, includes first-person exchanges between the subject and author Mike Stax).

No single volume can ever do justice to the froth and fervor of the New Wave and the many societal uprisings and destabilizations it reflected, but this is an excellent primer that differentiates itself from other treatises through its many-voiced perspectives and its gorgeous accompanying artwork. It’s nice to see Colin Greenland’s The Entropy Exhibition (1983), a book worth seeking out, referenced in these pages. Readers who want to go deeper, following a more traditionally academic route, may also enjoy Andrew M. Butler’s Solar Flares: Science Fiction in the 1970s (2012). But you’re still bound to learn new things from the work at hand. To name one, I’d never heard of William Bloom’s Qhe! series before opening the covers of this volume. As with any such collection, not every angle will be of equal interest to every observer; there are occasional repetitions, and moments of occasional stylistic dissonance. The date captions for the chosen cover art reference the specific editions shown, rather than those books’ first editions, which can be unintentionally misleading in the case of reprints, though admittedly it’s fun when different covers of the same title are juxtaposed.

Part of the glory of the New Wave, and its often-overlooked continuities with what preceded and succeeded it, is its messiness, its incursion into genres adjacent to SF, the thrall of its giddy, invigorating sprawl. In response to Thoreau’s ‘‘Simplify, simplify,’’ the New Wave might have cawed, ‘‘Electrify, electrify.’’ Dangerous Visions and New Worlds examines our genre during one of its most effervescent and vibrant periods. Adam Groves, in the context of the period’s surge of ‘‘weird erotica,’’ has written of an ‘‘imaginative fecundity that by today’s standards would be deemed politically incorrect.’’ That observation could apply to much New Wave fiction on the whole. The New Wave may have consciously styled itself as a disjuncture from Old Guard sensibilities, but as this volume illustrates, in so doing it unleashed a bevy of energies that still resist simple categorization and pre-emptively offended our own sensibilities. Nette & McIntyre aptly note in the Introduction that ‘‘while broader society has significantly changed and moral attitudes shifted, many of the social issues addressed by New Wave authors either remain or have been intensified, giving this body of work a continuing relevance.’’ As a teenager, I cut my teeth on New Wave science fiction. Though some critics and commentators have suggested that the New Wave had more bark than bite, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds makes it clear that this period of ferment and upthrust still offers plenty to chew on.

This review and more like it in the September 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.