Paula Guran Reviews Short Fiction: Black Static, Uncanny, Nightmare, The Dark, and Cemetery Dance

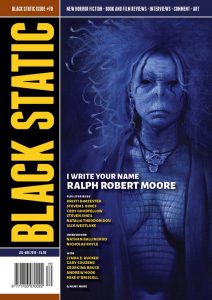

Black Static 7-8/19

Black Static 7-8/19

Uncanny 7-8/19

Nightmare 8/19, 9/19

The Dark 7/19, 8/19

Cemetery Dance 7/19

An outstanding issue of Black Static (#70) leads off with Ralph Robert Moore‘s novelette “I Write Your Name“. Roger was 14 when he met infant Mia. They meet again when Roger turns out to be 30-year-old Mia’s next-door neighbor – not that they recall their initial encounter. They fall in love and marry. Time goes by and Roger exhibits signs of a strange dementia. His behavior takes some gruesome and bizarre turns, finally resulting in a complete transformation that, from her response, Mia evidently understands and accepts. Things get odder still. Eventually, we are left with the idea that, indeed, love does not die.

In Kristi DeMeester‘s “A Crown of Leaves“, sisters Opal and Maribel return to the home in the Massachusetts woods they once lived in with their mother. Maribel recalls the past with far more fondness than her sister. Opal remembers a strange, witchy mother who communed with the woods, heard voices, and stuffed leaves in their mouths, and from whom they were taken away – ill-kempt nearly starved – twelve years earlier. Weird and well done.

In “Pendulum” by Steven J. Dines, Ellis and Milly’s much-desired son, Jack, is born – although it is never directly named – on the autism spectrum. Ellis deserts, refusing to have anything to do with his less-than-perfect son. Milly loves the child and copes. Told in the mother’s stream of consciousness, Dines masterfully uses the theme of the pendulum of life: “The Lion King… had it all fucking wrong. Life is not a circle but an arc. A great, invisible blade, scything nearer and nearer to the centre of us.” An unforgettable story.

In Jack Westlake‘s “Glass Eyes in Porcelain Faces“, Darren starts seeing porcelain masks in place of living faces – unremovable masks. A world of doll-faced people is, naturally, disturbing. Most of all he fears his wife’s face will “turn cold and hard, and her eyes will no longer be real.” Soon, though, they seem to be the only people with flesh faces left in the world. Darren determines to “protect” them. Things, of course, do not go as he imagines. Another good use of literary metaphor.

Jocasta, the protagonist of Cody Goodfellow‘s “Massaging the Monster” is an overworked masseuse who sometimes sees black crosses on her clients. She’s not sure what they mean, maybe “a sign of something in the client, some secret trying to make itself known.” Then she sees them on a man whose face she knows – the Devil incarnate. Using a technique she learned from her indigenous grandmother in El Salvador, Jocasta knows she could take away “all the pain from his evil deeds, but could she give a creature like this peace?” Skillfully and sharply written.

Mark, in “The Touch of Her” by Steven Sheil, feels a Connection with waitress Hannah, but after he touches her in a highly objectionable manner, he is banned from the café. His obsession continues as he searches for a way to re-establish the Connection. Moreover, Mark feels he needs to save her from a café patron, “The Toad,” who also likes Hannah. Things go very wrong for Mark and a form of justice is served in an over-the-top way that reminds me of prime John Shirley.

Natalia Theodoridou‘s “The Summer Is Ended and We Are Not Saved” is a commendable dark fairy tale. A wealthy bearded man with a locked room. A wife who knows the history of what has come before, but holds onto hope that he has changed, that this is finally a house she can call her own – but if you know anything of gods with the tendency to destroy rather than create, you’ll know not to hold too tightly to optimism. There is, however, some room for faith.

Uncanny #29 is another strong issue. In Sarah Pinsker‘s “The Blur in the Corner of Your Eye“, Zanna is mystery writer intent on finishing her book on deadline. To avoid distraction, she retreats to a remote cabin in the woods. Her friend/assistant Shar helps her get set up but stays nearby in a motel. The next morning, leaving the cabin in search of fuses to restore the electricity, Zanna discovers the dead body of her landlord. This one takes a zany horror turn. Most enjoyable.

A “big box” store appears overnight in Greg van Eekhout‘s “Big Box“, but it is far from your typical Wal-Mart. Its merchandise is arcane, bizarre, and magical – and offered at great prices. As our narrator notes: “Magic is always unpredictable. It’s always dangerous. It’s never cornflakes and toilet paper. But what’s wrong with magic people can afford?” What indeed? Another fun, light-dark story.

Rachel Swirsky & P.H. Lee‘s “Compassionate Simulation” is not fun at all. It’s a disturbing look at an abusive father-daughter relationship filtered through software. Original and moving.

In Marie Brennan‘s “On the Impurity of Dragon-kind“, the 15-year-old son of the world’s preeminent dragon naturalist displays his intelligence and loyalty to his mother as he explores orthodox faith and scripture with a sort of Midrash on the religious acceptability of dragons. Clever and especially noteworthy for fans of Brennan’s Lady Trent.

“Vegas,” A.C. Wise reminds us in “How the Trick Is Done“, “is a city of illusion, and everyone likes feeling they’re in on the secret, understand how the trick is done, but very few do.” So when the Magician dies instead of surviving his bullet-catching trick, there are matters to resolve, especially when the Magician has broken the heart of a former assistant as well as firing her, and her ghost shows up, and makes the acquaintance of another rejected assistant. But this is not a simple revenge story; it’s a strange and savory contemplation of life and death and resolution.

Maurice Broaddus begins with Creation and winds up in the interstellar future with “The Migration Suite: A Study in C Sharp Minor“. Throughout history, a family with roots in Ghana suffers injustice but also enjoys achievement. Poignant and sadly accurate, the reader is left with a feeling of triumph that justice finally prevails and despair that it would take so long.

Both of the originals in the August Nightmare have something to do with rites of passage. In Kurt Fawver‘s “The Bleeding Maze: A Visitor’s Guide“, a town forces its youth into their local maze at age 18. Most, not all, “have unique experiences, formative experiences.” The maze underscores their lives and, since the thing also bleeds, one must expect some strange outcomes. Fawver’s “guide” is darkly amusing.

The California (where else?) high school in Senaa Ahmad‘s “The Skin of a Teenage Boy Is Not Alive” has a demon that keeps getting trapped in teenage bodies: “Imprisoned in brittle, spidery limbs, in useless, still-mutating childbodies… an abracadabra of fury, itching to get out, crawling with the desire to be gone, waiting, just waiting to be incanted into something more.” High school is pretty much that way for everyone, though, isn’t it? Some are lucky and do escape. An unusual and agreeable story.

September’s issue of Nightmare offers the usual two originals. “Sweet Dreams Are Made of You” by Merc Fenn Wolfmoor is a brief near-future story about a two-player adult VR game, played in dreams and titled Vore, that sweeps the nation. Told in deadpan posts and descriptions, there’s a twist that should creep you out. Ray Nayler‘s “Beyond the High Altar” is a found-manuscript story. In this case, late-19th-century letters bought “in a bazaar outside the gates of the Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan in 2006.” The epistoler (“M”) and her husband Richard find (evidently “on the Afghan side of the Wakhan corridor”) a marble altar surrounded by hundreds of skulls. Their guides, refusing to stay in the place, leave for another location and give them a week to leave. Richard then encounters, as he has been told, a lone man with European features who supposedly has lived there for a thousand years. The man tells a “most extraordinary tale… which will change everything when we tell it,” and gives Richard what appears to be an Antikythera mechanism as proof of his tales. But, since “everything” wasn’t changed around 125 years ago, you can bet things do not end well. Nayler does a good job with the period details and characterization, but despite some atmospheric clues, I’m not convinced the core of the story holds together. I still appreciated it.

The Dark #50 is a special issue with four new stories rather than the usual two. In “Who Will Clean Our Spirits When We’re Gone?” by Tlotlo Tsamaase, Wame uses a strangely acquired business card to call a “spiritual consultant” in hopes of contacting her recently deceased girlfriend Goitseone. Goitseone and another girl, Izhani, have died in a headline-making fire. Jealous, Wame wants answers. Between an effective ending and beginning, the rest of the story is written in a challenging style that is, unfortunately, reader defeating.

In L. Chan‘s “The House Wins in the End“, the ghosts of Jia’s family and the haunted house that killed them pursue her for a decade. To defeat them she “interrogates other haunts; instead of being sought, she seeks out the dead fathers, the dead mothers, the dead sisters… she lays traps for them.” Jia is a survivor, but the haunted are strong. An appealing story that may need some patience, but is well worth it.

“The Dead Kings” by Teresa P. Mira de Echeverría (translated by David Bowles) puts us back in slightly challenging territory. “Grandfather” tells the nameless narrator a fantastical tale of growing up in a town “neither very close to nor very far from the powerful and great city of Aer” where dwelled the Dead Kings who rule it. Green centipedes with eyeless riders, “skittering silently and killing silently,” supply the kings with the deaths that make them ever more powerful. It’s a story with no relation to the reality of the trademarked world of Aer ruled by the corporations. Or is it? The story could have used an introductory section that sets the reader up for Grandfather’s tale. The lushly written fantasy gives away to more easily understood bizarreness, but sometimes one needs a bit of grounding when one starts into the weird.

Teacher Miss Augusta, in Kay Chronister‘s “Thin Places“, has been warned not to accept Lilianne Eisner, the new lighthouse-keeper’s daughter, into Branaugh’s sole school. The teacher defies the town’s dictate and enrolls the bright girl. The child recoils from the history, rituals, and customs she is taught of Branaugh – as well she should. Stories of outsiders who find themselves in villages with arcane customs are not, of course, uncommon. Chronister tells this one weirdly and well.

The Dark #51 has a pair of originals. In “It Is Not So, It Was Not So” by Megan Arkenberg, Pearl Voss takes tenants into her Chicago home. The ghosts of two (maybe three) former tenants also live there. Tenants may well have become ghosts due to the actions of their landlady. She’s taken in a new live renter, Karolin Dupre, who is fleeing from something – and Mrs. Voss wants to know what. Engaging and creepy. Benjanun Sriduangkaew‘s “Tiger, Tiger Bright” is exquisitely written, if not exactly much of a story. Khun Suvanan is suffering under a curse, but her work at a temp agency gives her some respite. A job for a women suffering under a curse crosses her desk and she responds.

I’m not sure one can refer to Cemetery Dance as a periodical, since it appears on a less-than-twice annually basis. It’s not even yearly if one averages it out. In any case, issue #77 has appeared and features six original stories. A woman wakes up as somebody else in “Like Life” by Gerard Houarner. Her journey is interesting, but the conclusion disappoints. “The Dead Leave Small Bones” by Ralph Robert Moore is about a middle-aged couple who discover skeletal metaphors for their lost love. Marci, in “Phantom Heart” by Terre LeMay, believes that a phantom lover impregnates her. Some originality, but I never felt we knew Marci well enough to invest. James Wraith White‘s “First Person Shooter” is a vividly written story about two young men who play an extremely violent video game. Unfortunately, it ends like so many other stories on that subject. In “Orange Grove” by Jason Sechrest, a suburban street is home to a grieving mother whose child has disappeared, a neighborhood snoop, a teen fascinated with a female neighbor, and an elderly gardener with some very special horticultural specimens. Nicely done and even suspenseful, but you will still guess the ending before the finale. Mark Rigney‘s “A Small Northern Inheritance” reads like a prose version of an episode for a Supernatural-type TV show – except the heroes seem to be around 60 years old. Bill Pronzini‘s “Crazy” is a first-person story about a madman, which has been told many times. Eric Rickstad‘s “Mowing for the Chicken” is a vicious story about a nasty teen and his equally nasty grandmother.

Paula Guran has edited more than 40 science fiction, fantasy, and horror anthologies and more than 50 novels and collections featuring the same. She’s reviewed and written articles for dozens of publications. She lives in Akron, Ohio, near enough to her grandchildren to frequently be indulgent.

This review and more like it in the October 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

Great stories, but what strikes me here are the magazine names – four of them bring outright depressing associations, and I doubt it is just my subconciousness. If these are the most important from the last surviving SF magazines, this rather says something about our collective conciousiness as genre readers.

The tile of this review might as well have been: Nightmare Dance under Black Static at The Dark Cemetery. 🙂

Or make your own permutaiton.