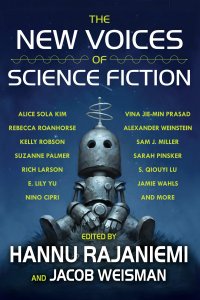

Paul Di Filippo Reviews The New Voices of Science Fiction, Edited by Hannu Rajaniemi & Jacob Weisman

The New Voices of Science Fiction, Hannu Rajaniemi & Jacob Weisman, eds. (Tachyon 978-1-61696-291-3, 432pp, $17.95) November 2019

The New Voices of Science Fiction, Hannu Rajaniemi & Jacob Weisman, eds. (Tachyon 978-1-61696-291-3, 432pp, $17.95) November 2019

In the deep past of our genre, how did one become a notable new writer? The first step back then was always the same as it is now: publish some good, standout stories as your apprentice and journeyman work. But subsequent public recognition in the days when print magazines dominated the discourse, prior to the internet, would accrue more slowly, from word of mouth and fanzine coverage and best-of-the-year inclusions.

To my knowledge, the initial attempt to formally showcase fledgling writers outside these traditional pathways happened in 1971, with the first of Robin Scott Wilson’s anthologies devoted to work by attendees of the famous Clarion writing workshop—by definition, new voices. Called simply Clarion, the book featured stories from such young up-and-comers as George Alec Effinger, Octavia Butler, Glen Cook, and Vonda McIntyre. A pretty respectable slate, as history showed us. Wilson compiled two more volumes, followed by a fourth helmed by Kate Wilhelm, and then there were some sporadic outings of the franchise in the subsequent decades.

Of equal importance was the series of anthologies devoted to work by those who won and were nominated for the Campbell award for best new writer. George R.R. Martin compiled four of these from 1978 through 1981.

Of course, with so much fiction being published first online today, and given the flourishing online forums and networks for readers, writers, publishers, critics, and editors, becoming a spotlighted new writer is a more dynamic and instant process. For instance, check out the column from 2018 by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro that highlighted “150 ‘new’ writers for your consideration.”

Nonetheless, a print anthology that features writers at the start of their careers can still serve a vital function by alerting the SF audience to worthy fresh contenders for the future title of Grand Master. We have such a volume on the table before us today, a companion to the award-winning 2017 selection, assembled by Weisman and Peter Beagle, The New Voices in Fantasy. The stories date from 2015 through 2019, and have all seen print before. But the editors range far and wide in their sources, and so even hardcore fans will probably find many unseen treasures here.

As usual in such gatherings, some of these folks are more firmly established than others, with one or more books to their credit already, while others are newbies of small but prominent output.

We kick off with the restrained and melancholy “Openness”, by Alexander Weinstein. In a future dominated by what’s practically a second mentality of augmented info, our protagonist finds that loving relationships require ancient skills now extinct. Nino Cipri goes beautifully nonlinear with “The Shape of My Name”, which chronicles the time-jumping autobiography of its protagonist, whose family has access to the one and only “anachronopede.” If you took Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Times series and cranked it up to eleven, you might end up with “Utopia, LOL?”, by Jamie Wahls, which thrusts a hapless baseline human into a giddy post-Singularity environment. The grand SF trope of brain-editing gets a sly new upgrade from S. Qiouyi Lu in “Mother Tongues”, which delves into the new ability to buy and sell linguistic birthrights.

Reminiscent of the weirdness of Ben Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet, “In the Sharing Place” by David Erik Nelson chronicles in vivid surreal fashion a post-invasion, post-collapse world where psychological counseling takes on dire new facets. Vina Jie-Min Prasad gives us a peek into a radical bioengineering scenario with “A Series of Steaks”, very topical in this era of Impossible Burgers. Thrilling, hard-edged, blackly humorous, “The Secret Life of Bots” by Suzanne Palmer bops back and forth between human and AI viewpoints as a failing old hulk of a starship tries to maneuver in wartime chaos. “Ice” is a tight little vignette about fraternal rivalry and also involving “frostwhales” on a frigid human colony world, brought to us in Rich Larson’s patented nth-generation cyberpunk style.

Riffing on a famous Bradbury story, Alice Sola Kim knits together the broken strands of one woman’s timeslip life in “One Hour, Every Seven Years”. In his underestimated classic Farewell, Horizontal, K.W. Jeter envisioned a world much like that in Jason Sanford’s “Toppers”, one where the resilience and adaptability of humanity is tested to destruction in a vertical landscape. Deploying poignant subroutines, Asimovian robo-Moms shepherd a young woman to adulthood in “Tender Loving Plastics”, by Amman Sabet. George Saunders and his “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” stand as patron saint to Rebecca Roanhorse’s “Welcome to Your Authentic Indian Experience™”, wherein authenticity and simulation vie for the soul of the protagonist. Slightly invocatory of Tiptree’s “The Man Who Walked Home”, “Strange Waters”, by Samantha Mills, chronicles the timeslip adventure of a humble fisherwoman named Mika Sandrigal as she crosses many vibrantly depicted eras.

Future Sweden is rife with down-and-out refugees from NYC in “Calved” from Sam J. Miller. Our father antihero has a son who has assimilated all too well to the host country, and the Dad seeks to breach the barriers between them, but perhaps too brutishly. A creepy Matrix-like vibe obtains in Lettie Prell’s “The Need for Air”, as a concerned but ignorant and biased mother attempts to force her open-air-loving son into a VR existence. “Robo-Liopleurodon!” by Darcie Little Badger almost compresses Annalee Newitz’s whole novel Autonomous into a vignette about biohacker pirates. A world divided into Doers and Donts (“The Doing and Undoing of Jacob E. Mwangi”), where our hero must break out of his antisocial inertia, demonstrates a kind of Cory Doctorow sensibility, but is still emblematic of the talents of E. Lily Yu.

Billy-Pilgrim-style timestream deracination, born of experimental drugs, plagues the title character in “Madeleine”, by Amal El-Mohtar. Bruce Springsteen could turn “Our Lady of the Open Road” by Sarah Pinsker into a whole album, as we observe a musician’s battle against insidious techno-artificiality. And finally, with Kelly Robson’s “A Study in Oils”, a somewhat unfairly maligned criminal, under sentence of arbitrary daily punishments, must endure exile from his beloved Luna in a future China whose virtues and attractions penetrate only slowly.

Aside from stating that this is a killer collection, full of top-notch stories beautifully written and invested with much care, compassion and thought, can any generalizations be made about this clade of “new voices?” Several authors really like narrating in the second-person, which was a big thing thirty-five years ago when Jay McInerney did it in Bright Lights, Big City. There is surely a lot of time-travel going on, reflecting perhaps the metaphysical condition of “atemporality” that Bruce Sterling has identified as a key feature of this era. This contributes to a lack of the old-fashioned sense of linear “progress” that SF once extolled. There’s also an intense focus on family relationships. Gone are the independent “adult” explorers and adventurers for whom childhood was merely a distant pleasant or unpleasant memory, seldom even mentioned. Of course the stories also exhibit a multicultural set of characters and venues. And while technocratic wonderland tomorrows are in short supply, there is no real dystopian counterbalance either. Rather, all these futures are realistic mixed bags.

But on the other hand, are any of these features so unique to 21st-century SF? Certainly, Judith Merril’s “That Only a Mother” revolved around family, as did many of Zenna Henderson’s People stories. You could even make a case for Heinlein’s reviled Farnham’s Freehold as a family psychodrama. Robson’s Lunar exile would feel at home in Fritz Leiber’s A Specter Is Haunting Texas (1969)—if you tossed in some of Maureen McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang (1992). And so forth and so on, teasing out valid old-school precedents for every story in this volume, in terms of themes, subject matter and narrative tactics.

By this, am I declaring these new voices unoriginal? Far from it! I am honoring them as shining bright avatars of all the classical gods and goddesses of SF who came before them. Deploying the toolkit and concerns bequeathed by their literary ancestors, they are extending the reach of the genre not by plowing under everything that was built before and salting the earth, but by erecting new superstructures on old foundations—or perhaps new eco-communes in the shadow of dinosaur cities. It’s the way the field has always moved forward, and this volume gives plenty of hope that the future of future fiction is in good hands.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.