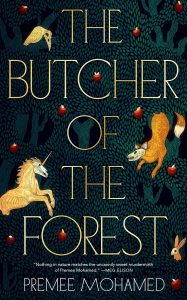

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The Butcher of the Forest by Premee Mohamed

The Butcher of the Forest, Premee Mohamed (Tordotcom 978-1250881786, $18.99, 160pp, tp) February 2024.

The Butcher of the Forest, Premee Mohamed (Tordotcom 978-1250881786, $18.99, 160pp, tp) February 2024.

I’m pretty sure that tales of forests that are haunted (or enchanted or forbidden or cursed or simply hallucinogenic) predate haunted-house tales by several centuries – in fact, they probably predate houses – and they’ve long provided powerful templates for fantasy (William Morris, George MacDonald, Tolkien, Robert Holdstock), horror (Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood) and even SF (Nnedi Okorafor, Jeff VanderMeer). So when someone revisits the form, as Premee Mohamed does with considerable vigor in The Butcher of the Forest, the question arises as to what the author wants to hang on this ancient template, and what’s new or different about it? Mohamed has no trouble coming up with images evocative of the shifting realities of an interior landscape – weird creatures, mysterious houses, untrustworthy helpers, endless traps, treacherous genius loci, and even a gaggle of zombie animals (perhaps her most haunting images). But the focus is mainly on the moral choices and dilemmas faced by Veris Thorn, a somewhat reclusive woman approaching middle age who is dragooned by a brutal tyrant (referred to only as the Tyrant, suggesting the archetypal tone of the story) to rescue his errant kids, who have wandered off into the forbidden woodland called Elmever, from which supposedly no one ever returns. Veris’s sole qualification, it turns out, is that she is the only one who has ventured into the wood and brought someone back; the Tyrant has already lost a few guards simply trying to approach the wood. Veris feels no loyalty toward the Tyrant, who was responsible for the deaths of her parents along with thousands of others, but he threatens not only to burn and raze her village, but to “roast your people alive upon it and eat them.” Though not really a major figure, the Tyrant’s combination of fairytale evil king, Bond villain, and real-life genocidal dictator gives some sense of the mix of different discourses Mohamed is working with here.

Like many haunted forests, Elmever has its own arbitrary rules, which echo both classic fairytale lore and contemporary gaming: “don’t cut living wood; don’t shed any animal’s blood; trade if you must, but do not negotiate. And certainly never accept any gifts.” It’s uncertain just how firm these rules are, since Veris seems to negotiate with all sorts of figures later on, and even claims that “no creature of the Elmever would turn down a deal.” Guided by a handful of magical tokens and her own fraught memories of her earlier not-entirely-successful adventure – “snouts drooling and panting in the darkness, of fangs and claws, things that moved in silence even on these loud, dry leaves” – she first encounters some fairly familiar animals, like a pack of wolves and a talking crow, but it’s not long before the figures grow more hallucinatory, including a weird, flat, flapping carnivore, fruits that seem straight out of “Goblin Market”, a house reminiscent of Hansel and Gretel, and those zombie-like skeletal animals. Trying to separate the real from the illusory proves as challenging as learning who to trust among a succession of figures, including an archetypal trickster fox – but all this is complicated by Veris’s constant awareness that her task involves rescuing the children of the man who murdered her own family and is threatening to wipe out her entire village. Fairy tales traditionally don’t traffic much in characterization and moral ambiguity, but Veris emerges as an increasingly intriguing figure who is repeatedly forced to make choices that lend this already dark version of familiar materials a surprisingly rich and complex texture, written in a lyrical prose that is as clear, vivid, and elegant as that of classic literary folktales.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, and a similar set for the 1960s. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the February 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.