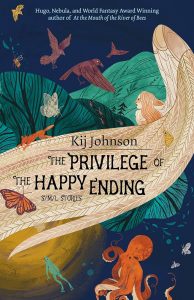

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The Privilege of the Happy Ending by Kij Johnson

The Privilege of the Happy Ending, Kij Johnson (Small Beer 978-1-61873-211-8, $18.00, 302pp, tp) October 2023.

The Privilege of the Happy Ending, Kij Johnson (Small Beer 978-1-61873-211-8, $18.00, 302pp, tp) October 2023.

It’s been more than a decade since Kij Johnson’s second story collection, At the Mouth of the River of Bees, and while no one is likely to accuse her of reckless profligacy since then (she’s been busy with academia, among other things), no one is likely to accuse her of playing it safe, either. Two of her most prominent publications have invoked writers as wildly divergent as H.P. Lovecraft and Kenneth Grahame, and some of the short fiction included in The Privilege of the Happy Ending is about as experimental in form as anything I’ve seen in genre venues for some time. While there are a dozen stories in the collection (or 14, if you count the three parts of her ‘‘Apartment Dwellers’’ series as separate pieces), more than half the book is devoted to her two World Fantasy Award-winning stories ‘‘The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe’’ and ‘‘The Privilege of the Happy Ending’’. The former is her deservedly famous reinvention of Lovecraft’s ‘‘The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath’’, replacing his stalwart Randolph Carter with a math professor at a women’s college deep inside the dreamworld that Carter sought to visit. Faced with a vaguely medieval society already skeptical of women’s education, the college of Ulthar (another name borrowed from HPL) faces an existential crisis when one of the students, whose father is a trustee, runs off with her boyfriend to visit the ‘‘waking world.’’ Vellitt Boe sets out to track her down, inverting Carter’s initial quest into the dreamworld with an equally hazardous quest out of her dreamworld, called the Six Kingdoms. Along the way, she has to contend with many of the same Lovecraftian hazards that Carter had to face, including Zoogs, Gugs, Ghasts, Ghouls, and other critters that sound like discontinued breakfast cereals. Transforming a tale by a writer who could barely bring himself to even mention female figures into a fable of feminist empowerment is an achievement in itself (quite apart from Lovecraft’s various other problems), but Johnson’s version is if anything more coherent than Lovecraft’s, and the ending has the neatest twist in the collection.

‘‘The Privilege of the Happy Ending’’ is, as its title implies, one of several pieces that interrogate the very nature of storytelling, but the story itself combines elements of medieval dream vision, animal fable, and apocalyptic horror. Sometime in the twelfth century, a six-year-old orphan named Ada befriends a talking hen named Blanche, and when the countryside is overrun by swarms of ravenous wastoures, ‘‘scarce larger than chickens but unfeathered and wingless, snake-necked and sharp-beaked and bright-clawed’’ (the term is a Middle English word for something that lays waste), Blanche turns out to be wise enough to find protection for them. As they make their way through a kind of Pilgrim’s Progress landscape, visiting settlements with names like the Unlucky Village and the Lucky Village, they face accusations of witchcraft (a talking hen!), but eventually learn that Blanche is more than she at first seemed (though, as Johnson’s sometimes deliberately intrusive narrator points out, the happy ending depends in part on where you choose to end the tale). With that self-conscious narrative voice, it somehow achieves the feel of both oral legend and postmodern fantasy.

The most purely entertaining – and most conventional – tale is original to the collection. ‘‘The Ghastly Spectre of Toad Hall’’ is a Christmas ghost story set in the Wind in the Willows world as revisited by Johnson in her own delightful The River Bank. When the familiar crew – Toad, Water Rat, Mole, Mole’s sister – discover that Toad Hall is haunted by a spectre whose presence portends the death of the master of the house, their comical efforts to save Toad from his fate seem foiled by a blizzard, until another neat ending provides an unexpected resolution. ‘‘Ratatoskr’’ is drawn from the Norse myth of the squirrel who serves as messenger on Yggdrasil – and who seems to appear outside the window of a ten-year-old girl in Iowa in the 1960s (‘‘This is Ray Bradbury country’’). What initially looks like it might be a conventional monster-under-the-bed horror story instead becomes a haunting lifelong mystery to the girl, who among other things learns to befriend the ghosts of squirrels. Another 1960s Iowa girl shows up in ‘‘Five Sphinxes and 56 Answers’’, which counterpoints her lifelong fascination with riddles with variations on the most famous riddle-tale of them all, Oedipus and the Sphinx (who here becomes a rather put-upon character called Phix, trying to figure out what these humans are up to). This story leads us toward the more fully experimental mode, deliberately playing with the reader by inserting dozens of answers to riddles without telling us what the riddles are (though a few are pretty familiar). The other original story in the collection is also a riddle tale, the very short but funny ‘‘Crows Attempt Human Style Riddles, and One Joke’’.

Other stories draw on Old Testament mythology (‘‘Noah’s Raven’’, which adopts the title figure’s point of view), Coyote trickster tales (‘‘Coyote Invents the Land of the Dead’’), and dream imagery (‘‘Butterflies of Eastern Texas’’, a strangely poignant tale of a bored train conductor dealing with an unticketed passenger who issues butterflies each time she speaks). By now, though, we’re moving into still more experimental narrative territory, revealing Johnson’s fascination with catalogs and lists at the expense of traditional plots. ‘‘Mantis Wives’’ is a graphic list of ways in which female mantises devour their mates, while ‘‘Tool-Using Mimics’’ offers a variety of interpretations of a surreally altered vintage photograph by the artist Laura Christensen, finally settling on an account of a girl performer in the 1930s. Another artist, Jason Baltazar, provides a series of rune-like figures for ‘‘The Apartment-Dweller’s Stavebook’’, one of a series of three ‘‘guidebooks’’ (the others are ‘‘The Apartment-Dweller’s Bestiary’’ and ‘‘The Apartment-Dweller’s Alphabetical Dreambook’’) all shifting between second-person and third-person narration to reveal tantalizing fragments that may or may not suggest hidden or unrealized tales. If the nonnarrative selections in The Privilege of a Happy Ending might prove disorienting to readers who prefer the more familiar narrative movement of the title story, it’s worth remembering that one of the signature stories of Johnson’s previous collection At the Mouth of the River of Bees was titled ‘‘Story Kit’’. It’s a good description of several of these fictions as well – enigmatic, allusive, poetic, fragmentary, and sometimes oddly moving – but with some assembly required.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the October 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.