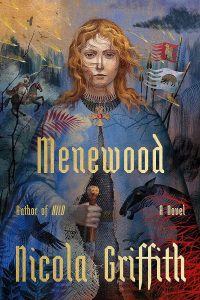

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Menewood by Nicola Griffith

Menewood, Nicola Griffith (MCD/Farrar, Straus, Giroux 978-0-37420-808-0, $35.00, 720pp, hc) October 2023.

Menewood, Nicola Griffith (MCD/Farrar, Straus, Giroux 978-0-37420-808-0, $35.00, 720pp, hc) October 2023.

When her novel Hild was published back in 2013, Nicola Griffith wrote a short essay for Tor.com addressing reviews which described her as a distinguished SF/F writer who had somehow jumped ship into historical fiction, or which asked whether the novel itself could be read as some sort of fantasy. I even saw it described as ‘‘speculative historical fiction,’’ which seems to me pretty redundant (how can historical fiction be anything but speculative?) What was really going on, I suspect, was simply that a number of SF/F readers, and in particular fans of Griffith’s work, wanted to give themselves permission to indulge in a beautifully written and meticulously researched but pretty fat historical novel with no material fantasy in it at all. As dilemmas go, this one is pretty silly, but the question is likely to come up again with Menewood, which is substantially longer than Hild even though it covers less than four years in the life of the woman who would become St. Hilda of Whitby, whereas the first novel covered her entire childhood to the age of eighteen. And in many ways, it’s a different sort of novel entirely. Hild told of the coming of age of a bright, willful, and almost preternaturally observant girl whose ability to perceive patterns in both nature and human behavior led her to become a trusted adviser and seer for her great-uncle, King Edwin of Northumbria. Married to her half-brother Cian, she became the Lady of Elmet, charged with protecting the region from possible incursions, thus protecting the southern borders of Northumbria.

Menewood begins only months after the end of Hild, and Hild’s talent for pattern recognition is as shrewd as ever. She’s still a keen observer of nature (and a pretty good weather forecaster), but now she’s increasingly called upon to use her skills in politics, economics, and strategic warfare, and she’s feeling the emotional burden of being ‘‘Hild Yffing, light of the world and godmouth, haegtes and freemartin, Butcherbird and king’s fist’’ (and yes, Griffith provides a very useful glossary for puzzling some of that out). The novel begins and ends with the same suggestive image, as Hild watches a water vole in a pond and wonders if it’s ‘‘swimming home to safety, or away in search of adventure.’’ Hild’s safe home is Menewood, the tiny settlement in a secret valley hidden behind forbidding bogs, where she has established her own sort of Shangri-la, a sort of mini-utopia with no slaves, equal property sharing, and trusted friends like her life companion Begu and her loyal bodywoman Gwladus. Of course, she’s soon called away on duty, first to successfully quell a nearby incursion and later to travel north to secure an alliance important to the rather petulant King Edwin, who isn’t at all happy that his most cherished defender has gotten herself pregnant.

For all its density of detail, political complexity, and brilliance of characterization, the novel’s overall plot is rather straightforward: After her successful diplomatic mission, Hild and her allies are faced with a far more dangerous threat from the south, an alliance of rival kings named Penda and Cadwallon, the latter who becomes the tale’s chief villain, an outrageously brutal warlord whose armies lay waste to everything in their path. Returning from a disastrous battle (now known historically as the Battle of Hatfield), Hild regroups in a comparatively quiet interlude in Menewood before leveraging her various alliances to prepare for a climactic confrontation with Cadwallon. For reasons best left for the reader to discover, this time it’s personal for Hild (I know, that’s a cliché from every revenge tale ever told, but it’s pretty accurate here), and the final fifth of the novel is compelling not only in its precise descriptions of Hild’s formidable strategies, but in its sheer kinetic pacing. Some readers may feel that it takes quite a while to get there – and it does–but the deeply complex relationships developed throughout the novel are necessary for us to fully appreciate the stakes, both for Hild herself and in terms of the historical forces at work, which will eventually shape Britain.

So, to get back to our original question, what does Menewood promise for the SF/F reader, and why are we talking about it in Locus? Apart from the distinct possibility that this may be the major work so far of a major talent, there’s quite a bit. From the fantasy reader’s perspective, seventh-century Northumbria is such a little-known corner of history that it feels as thoroughly estranged as any imaginary kingdom, and Griffith’s decision to make extensive use of unfamiliar terminology adds to the estrangement; by the time we’re done sorting out all the gesiths, thegns, aethelings, and ealdormen, we’re grateful for that glossary, as well as for the maps and dramatis personae. (At one point, Hild’s lover Brona, a female butcher who is one of the novel’s best characters, says to Hild, ‘‘Oswiu. Oswald. Oswine. Osric. I don’t know how you keep them all straight,’’ and we know how she feels.) There are any number of points where characters mention wights, sprites, or fairies, but bringing them onstage would add nothing. (For that matter, does the insertion of Hild into real historical events make it a secret history?) SF readers, on the other hand, will recognize the importance of Hild’s sheer competence throughout (she could outthink a Heinlein hero), as well as her fascination with how things work. We learn how to make parchments, dyes, and inks; what sort of land is best for grazing sheep for wool vs. sheep for milk, how to butcher a horse, even (quite literally) how the sausage is made (and in the hands of Brona and Hild, it can be weirdly sexy). If Hild showed us that close observation and inference could be mistaken for magic and vision, Menewood convinces us that the magic is embedded in history itself. And (since we can check the historical record), we know that Hild still has more than four decades of history to go. What’s next?

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the October 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.