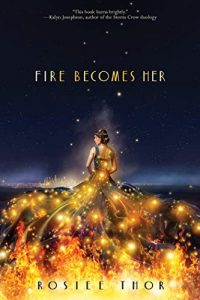

Alex Brown Reviews Fire Becomes Her by Rosiee Thor

Fire Becomes Her, Rosiee Thor (Scholastic 978-1-33867-911-3, $18.99, 368pp, hc) February 2022.

Fire Becomes Her, Rosiee Thor (Scholastic 978-1-33867-911-3, $18.99, 368pp, hc) February 2022.

In Rosiee Thor’s Fire Becomes Her, Candesce, a nation similar to the United States in the 1920s, is on the cusp of an historic presidential election. Gwendolyn Brooks, a former entertainer, is challenging Senator Holt, an excessively wealthy man everyone believes is a shoe-in. When she was a child, Ingrid Ellis’s father was thrown in jail for bootlegging flare, the magic in this world. After earning a scholarship to a hoity-toity academy, Ingrid vowed to never let herself be defined by her father’s actions. Over the years, she climbed her way up the social ladder, in part by attaching herself to Senator Holt’s son, Linden, who the press believes will one day run for president himself.

Now, with the election imminent, it’s time for Ingrid to make her move. To prove herself to the senator, she embeds herself in the opposition’s campaign as a spy. However, the more she learns about Gwendolyn’s policies and plans for Candesce, the less comfortable she feels with the prospect of a Holt presidency. Alex, one of Gwendolyn’s assistants, takes Ingrid under his wing, and something sparks between them, not romance but something bigger and deeper and less easily understood by Ingrid. Soon Ingrid will have to choose between a future where she can never be herself and one where she must sacrifice her dreams.

If you like flawed main characters, you’re going to love Ingrid. She is a smart young woman who could grow up to be a clever adult if she ever figures out how to get out of her own way. Ingrid is a hot mess of epic proportions. Every time she’s offered a choice, she inevitably picks the worst, most chaotic one. She does this under the guise of trying to get ahead, but each time she takes a step forward she immediately shoots herself in the foot. Yet throughout all this, Rosiee Thor carefully manages Ingrid’s identity. Not fully understanding her queerness leads her down some difficult paths, but Thor never makes it feel like being a bisexual aromantic is in itself a flaw.

It is unfortunately not uncommon for allosexuals and alloromantics to see those on the asexuality or aromanticism spectrums as not having valid identities, as needing to be fixed. The same goes for cis authors attempting trans and nonbinary/genderfluid/genderqueer stories. Even those claiming to be allies often fall into allo- or cisnormative language and tropes, and can unintentionally perpetuate harmful stereotypes while attempting to write diversely. In recent years, speculative fiction fans in both young adult and adult have been blessed with an ever-increasing amount of works featuring characters across the asexual, aromantic, and gender spectrums. (For those keeping track, out of all the characters in Fire Becomes Her, only two are heterosexual; the rest are queer, including lesbian, bisexual, aromantic, asexual, nonbinary, and transmasc.)

As an ace/aro genderqueer person, this new run on expanding how queerness is written about has made reading less of a minefield because now I have way more OwnVoices options to choose from. I try not to get too hung up on OwnVoicesas a label – my main concern is that the writing feels authentic without trying to also be all-encompassing – but oftentimes you can see the lived experience in the seams: the private thrill Ingrid feels when she meets someone who is also queer but more open and confident in their identity, the fear that because you don’t perceive relationships the way most people do you’re doing it wrong or there’s something wrong with you, that the way you feel in your body doesn’t match the way you feel about your body or the way other people interpret your body. Through Alex and Ingrid, cis and allo readers get a nuanced look at some less commonly portrayed queer identities, while nonbinary and arospec readers get to see the truth of our experiences writ large.

The only real area of weakness in the novel is its worldbuilding. Thor keeps the focus tight on Ingrid, so much so that we get little exploration of the world around her. Although the characters travel to different cities and neighborhoods, the reader has little idea about the layout or socio-cultural makeup of the areas. Flare and flicker (the diluted, handmade version of flare) are explained just enough for them to make sense for the plot, but that’s about it. At first it isn’t much of an issue, but later, as Ingrid’s use of flare shifts into something more unique, it becomes a bit confusing.

More on the history of Candesce and the roles flare and flicker played in its development would have gone a long way as well. It’s obvious the election battle between Gwendolyn and Holt is crucial, but some historical context would have given it even more weight. The parallels to the real 1920s are both good and not quite enough. We see much of the gilded affluence of the Jazz Age and the consequences of Prohibition, but little of the push for and backlash to social progress or the massive migrations from rural areas to metropolises. I don’t want to nitpick a fiction book for not being more historically accurate, but these social issues are what drive the flair and fury of the 1920s.

Structurally, the novel feels more like a political thriller with a fantasy twist than a standard historical fantasy. The pace is a bit slower than I expected, but it worked for me. The bursts of intense action help break up the quieter, more personal moments. Where Thor shines is in her descriptions. She sinks us into Ingrid’s mind and gives us an evocative, detailed look at her small slice of the world. She can also write the hell out of action scenes, filling them with heat and intensity, motion and flow. The premise of fire-based magic is not wasted when it comes to fighting.

Overall, Rosiee Thor’s Fire Becomes Her is entertaining and emotional. It’s the kind of standalone that makes you long for more while appreciating what you’ve got. There are so many secondary characters who are so well developed, they could easily helm their own novels in this same world. The book is everything I love about young adult fantasy fiction.

Alex Brown is a queer Black librarian and writer. They have written two books on the history of Napa County, California’s marginalized communities. They write about adult and young adult science fiction, fantasy, and horror as well as BIPOC history and librarianship. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and access set the foundation of all their work. Alex lives in Southern California with their pet rats and ever-increasing piles of books.

This review and more like it in the April 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.