Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Reconstruction by Alaya Dawn Johnson

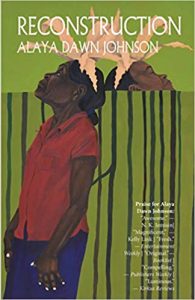

Reconstruction, Alaya Dawn Johnson (Small Beer 978-1-618731777, $17.00, 278pp, tp) November 2020.

Reconstruction, Alaya Dawn Johnson (Small Beer 978-1-618731777, $17.00, 278pp, tp) November 2020.

Like a number of writers who have arrived with a splash in the last decade or two, Alaya Dawn Johnson seems to have written nearly as many novels as short stories. That’s not actually the case, of course – her website lists seven novels, and her first collection, Reconstruction, contains ten stories – but it’s probably fair to say that Johnson’s rapidly rising reputation derives mostly from those novels, and from a few stories reprinted in “year’s best” anthologies and one quite distinctive Nebula winner. I have no idea if Johnson has felt more comfortable with longer forms, as N.K. Jemisin said she was in her introduction to her first collection last year, but as with Jemisin’s collection, it’s not hard to view these stories as a way of testing different waters, experimenting with genre boundaries, trying out different styles, forms, and themes. This is one reason I find first story collections so fascinating: they show us, intentionally or not, a writer in the process of working things out, of trying out voices and settings and protocols, of – as is clearly the case with Johnson – challenging herself in finding what’s comfortable and what seems risky. Thus, we get a story constructed from documents and news reports, another told partly in poetry, another cast as an historical memoir. We get settings as diverse as a grim, post-apocalyptic Mexico City; a radically estranged far-distant Vancean future; the Civil War South; and a near-contemporary New York. We get characters who range from annoyingly privileged summer camp adolescents, to an aging idealistic biologist, to demons and vampires.

The lead story is the Nebula Award winning “A Guide to the Fruits of Hawai’i”, whose lush setting dramatically contrasts with the dark dystopian horror theme: vampires have basically conquered the world, maintaining concentration camps for human victims and more elite reservations and “mommy farms” (as much as I detest “x-meets-y” blurbs, the story intermittently reminded me of the very different films Daybreakers and The Descendants, thought it isn’t much like either). Johnson offers a very different take on vampires in the most mordantly witty tale here: “Their Changing Bodies” is set among the predictable class rivalries of an overprivileged summer camp, but offers a delicious reversal once the vampires show up (although Johnson has to set up some fairly convoluted rules of vampirism for the plot to work). As different as they are, both stories reflect Johnson’s recurring concern with power differentials – whether the product of gender, race, family, religion, or alien invasions – and how they might be resisted, subverted, or at least survived.

The alien invasion story, “They Shall Salt the Earth with Seeds of Glass”, with its echoes of classic SF going all the way back to Wells’s War of the Worlds, not only features aliens mostly invisible behind their robots and with ominous motives, but also takes place in a familiar landscape (mostly Maryland, apparently) weirdly transformed by the invasion, notably featuring a giant transparent pipeline that one character thinks might be some sort of wormhole. Those transformed, sometimes phantasmagoric landscapes turn out to be another Johnson trademark. The alien world in “Down the Well”, the hardest SF story here, initially discovered through a wormhole deep in the Earth, is basically the creation of a brilliant biologist who takes advantage of the vast time differential – a million years there to 23 days here – to stage her own experiments in planetary evolution. The most bizarre setting, though, shows up in “Third Day Lights”, the most radically estranged story in the collection, which begins with, “The mist was thick as clotted cream, shot through with lights from the luminous maggots in the sand.” That black sand, it turns out, has the property of freezing whatever touches it, and the world only grows stranger from there. The narrator, a shape-changing wizard, is visited by a posthuman supplicant and gives him three tasks, resulting in a kind of gnostic deal-with-the-devil tale as visualized by Hieronymus Bosch.

The story which most ambitiously experiments with form, “Score”, is set in New York and assembles documents over two decades to unfold a story that touches upon political protest, crackpot visionaries (treated with something more thoughtful than easy ridicule), and apocalyptic portents, while “Far and Deep”, which concerns a rebellious daughter defying the elders to honor her mother with a ritual funeral, seems to share the mythic Polynesia of her Spirit Binders trilogy. Of particular interest, though, are the two original stories, “The Mirages” and “Reconstruction”, each of which seems restrained compared to the coruscating imagery of some of the other tales, but which feature some of the most memorable characters of all. “The Mirages” takes place in a future Mexico City that has become such an overheated environmental hellhole that people have to live in airlock-protected underground chambers, but the focus is on a once-dissolute father trying to bring his daughter a birthday gift – a simple but now-precious tortilla and some possibly contaminated fruits – as the mother and her new partner plan to move with her to a now-temperate settlement in northern Canada. The familial pain and sense of loss is so acutely realized it barely needs its SF setting. Similarly, “Reconstruction” is narrated by a laundress and cook who accompanies the First South Carolina regiment – the first to be made up of mostly escaped slaves – in the waning months of the Civil War. While Sally, the narrator, has inherited some conjuring skills from her great-grandmother, supernatural interventions are less central to the tale than Sally’s haunting sense of sacrifice and loss, remembered years later, or the provocative “taxonomy of anger” once taught to her by a young freeborn gunner named Flip. It may be the least fantastic tale here, and it may be the best, featuring some of Johnson’s richest characters and a narrator whose voice achieves a genuine gravity of mourning. In addition, it makes a thoroughly compelling case for the importance of understanding and remembering the uses and varieties of anger.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the December 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.