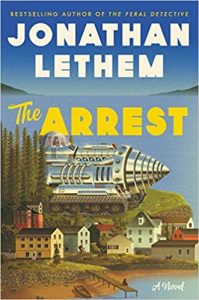

Gary K. Wolfe and Ian Mond Review The Arrest by Jonathan Lethem

The Arrest, Jonathan Lethem (Ecco 978-0-06-293878-7, $27.99, 320pp, hc) November 2020.

The Arrest, Jonathan Lethem (Ecco 978-0-06-293878-7, $27.99, 320pp, hc) November 2020.

A little more than halfway into Jonathan Lethem’s The Arrest comes a chapter titled “Postapocalyptic and Dystopian Stories”, in which the screenwriter protagonist and his movie-producer friend debate the appeal of such tales while name-checking a panoply of authors and titles – Vonnegut, King, Atwood, Walter Tevis, Philip K. Dick, George R. Stewart, Walter M. Miller, Emily St. John Mandel, Russell Hoban, and especially Cormac McCarthy. McCarthy’s The Road “bugs the fuck out of me,” complains the producer, calling it “postapocalyptic comfort food” and arguing that, far from offering real cautionary tales, most of these writers “can’t help it, they like it there. They love it there.” It’s a point which has been made before, and it’s only one of the many ways in which Lethem’s oddly jaunty novel comments on and satirizes its own literary landscape. The central conceit is disarmingly simple: gradually, but over a short time, just about all technology ceases to work, from TVs and smartphones to computers, internal combustion engines, airplanes, even guns and bullets. While characters briefly speculate on possible causes, from solar flares to “species revenge,” it’s clear from the outset that Lethem isn’t much interested in the question. What he is interested in is settling us into the sort of post-apocalyptic pastoral landscape that several of those earlier novels pioneered, forgoing panoramic wastelands in favor of a tight focus on a small community for which the larger global disaster is mostly a matter of rumor and speculation – what Brian Aldiss called the cosy catastrophe.

The screenwriter, Sandy Duplessis (now calling himself Journeyman), finds himself trapped in the coastal Maine town of Tinderwick, where he had been visiting his sister Maddy when the Arrest happened. Maddy’s home town, having already turned itself into a back-to-nature redoubt, was more prepared for the Arrest than most communities, and some seemed to almost welcome it. But with few useful skills in the new subsistence economy, Journeyman works as a deliveryman for the local butcher, which sometimes brings him into contact with nearby communities such as the Cordon, a rather militant group whose ambitions may have been stunted when their guns stopped working. The plot begins when a member of the Cordon approaches Sandy with the news that a stranger has appeared, asking about Sandy and Maddy and driving a gigantic, nuclear-powered “supercar” – a sort of amalgam of a steampunk earth-boring machine and the armored Landmaster from the film Damnation Alley (which gets a brief shout-out, as does Chitty Chitty Bang Bang). The stranger turns out to be an old collaborator from Sandy’s Hollywood days: the superproducer Peter Todbaum, who had enlisted Sandy as a screenwriter and script doctor and who dreamed of producing a big-budget alternate-world SF epic called Yet Another World (interestingly, the same name Lethem gave to his fictional version of Second Life in Chronic City). Todbaum has driven the car, which he calls the Blue Streak, all the way cross-country from California just to track down Sandy and Maddy.

During those earlier Hollywood days, centered around a 1930s-style complex called the Starlet Apartments, Maddy arrived for a visit, quickly gaining Todbaum’s attention and abruptly leaving after some sort of apparently erotic encounter with him. (All this may seem familiar to those who read Lethem’s New Yorker story “The Starlet Apartments” last year, which recounted the same events in first person.) Maddy is easily the most interesting character in the book – taciturn, resourceful, determined, even “saturnine” in Sandy’s view – and for most of the novel her endgame remains a mystery to Sandy and to us. Her romantic partner, a Somali woman and former beekeeper named Astur, is more cheerful and forthcoming, and even becomes one of Sandy’s few friends, though remaining resolutely protective of Maddy.

For his part, Todbaum credits Maddy with having provided a crucial plot element for his sci-fi epic (and it is “sci-fi,” in the most Hollywood sense), viewing her as a kind of muse – though she wants nothing to do with him. At first Todbaum fascinates the locals, not only because of his supercar (whose nuclear engine mysteriously seems to work despite the Arrest), but because of his apparently endless supply of coffee and his charismatic tales of Hollywood. Needless to say, this eventually gives way to distrust, and a scheme emerges to steal the car – though the actual fate of the Blue Streak turns out to be far more bizarre. With its colorful cast of eccentrics, constrained setting, playful structure of interleaved tales (sporadically illustrated with what appears to be clip art from sources as varied as The Wicker Man and an old Superman comic), and its scattershot satire, The Arrest often feels less like a post-apocalyptic survival tale than a pastoral screwball comedy. In the context of all those dystopian tales that Todbaum complains about, it’s something of a tonic, and we can easily understand why Lethem might just love it there.

–Gary K. Wolfe

About halfway through Jonathan Lethem’s new book The Arrest, Hollywood producer Peter Todbaum takes issue with the idea that doomsday narratives are cautionary tales. He argues that the authors who write this “Post-apocalyptic comfort food,” like Stephen King, Russell Hoban, and Cormac McCarthy, are seduced by the opportunity to clean the slate, to rid the world of any ambiguity. “They just can’t help it,” he explains. “They like it there. They love it there…. They want to live there, you can feel it.” What’s provocative about Todbaum’s criticism – which I have some sympathy for – isn’t so much his crack at Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (“If [he] were honest he’d admit he wrote a campfire story”) but that The Arrest is set after a global catastrophe that has brought civilisation to its knees. But then, it’s that sort of novel: as much a playful swipe at apocalyptic stories as it is about the end of the world.

The title refers to Lethem’s peculiar brand of apocalypse. Instead of zombies, pandemics (thank God), or nuclear war, the Arrest is the nickname for a series of events that sees technology gradually cease working. Our narrator Alexander Duplessis, who goes by the name Journeyman, has ignored the sixth mass extinction, melting ice-caps, and the flooding of major cities, and only becomes aware of the end of the world when he notices the death of screens. It starts with television, which “contracted a hemorrhagic ailment” but then spreads to “Gmail, the texts and swipes and FaceTimes, the tweets and likes.” And it doesn’t end there. The Arrest also bids farewell to:

Gasoline and bullets and to molten flourless cake… to coffee… to bananas and Rihanna, to Father John Misty, to the Cloud, to news feeds full of distant core meltdowns, to manatees and flooded cities and other tragedies that Journeyman had guiltily failed to mourn.

Does Lethem ever explain the cause of the Arrest? No. Does it matter? Not in the slightest.

Most of the novel is set around the fictional town of Tinderwick, situated on the coast of New Hampshire somewhere near Portsmouth (I’d like to be more precise but I’m not a New Englander). It’s also the location of Spodosol Ridge Farm, managed by Journeyman’s sister, Maddy, and where he happens to be visiting when the Arrest kicks into gear. Journeyman decides to stay at the Farm, partly because it would be suicidal to head back to Los Angeles, but mostly because his job as a Hollywood screenwriter (really a Script Doctor in the mould of William Golding) is surplus to requirements. With everyone expected to work, Journeyman’s post-Arrest gig is to help out the local butcher and deliver meat for the residents. He’s on his daily run when he’s approached by a member of the Cordon: the ragtag, vaguely threatening bicycle gang that protects, but really surrounds, Tinderwick. An old friend of Journeyman and Maddy’s has arrived at the border, miraculous given the danger and difficulty travelling across an untamed, technologically bereft country, but all the more astonishing because the stranger has turned up in a car. Not any ordinary vehicle either, but something straight out of the Pulps, a nuclear-powered monster, a “shiny abysmal engineered carcass… a jet engine or hydrogen bomb… mounted on a fantastic chassis.”

The operator of this metal colossus, dubbed the Blue Streak, is Peter Todbaum (the same Peter Todbaum who didn’t much like The Road). The novel pivots on his 30-year relationship with Maddy and Journeyman. There are flashbacks to Todbaum and Journeyman’s post-college days, and particularly the time Maddy came to visit both of them when they stayed at the Starlet Apartments in Burbank, both with dreams of making it big as writers in Hollywood (and to be fair, one of them did). What becomes clear during these recollections of things past is that Journeyman is a third wheel, the middleman between two vastly different, very forthright personalities. This relationship extends to Journeyman’s time in Hollywood, where he becomes Todbaum’s lackey, and his life in Tinderwick where he’s a minor cog in a larger cooperative managed by his sister. Journeyman isn’t so much an anti-hero as an anti-apocalypse hero. He doesn’t fight off zombies or bring down insane religious cults, all in the aim of building a better world; instead he acts as a go-between, with no agency of his own, delivering messages between Todbaum, encamped in his marvellous Blue Streak (I love that car), mesmerising the townspeople with stories about the last dregs of civilisation, and Maddy who refuses to pay the Hollywood producer any attention. And it’s Lethem’s dedication to playing against typical post-apocalyptic tropes, replacing the roving Mad Max like gangs, the insane cults, and the hardscrabble, kill-or-be-killed, existence, with a tattered bunch of blokes on bikes, a loudmouth filmmaker in an impossible vehicle, and a village famous for its delectable sausages, that makes The Arrest such a blast to read. While the novel was written before the plague, as fate has it, this is the one (anti) end-of-the-world novel that’s both safe to read and also encapsulates the surreal, strange quality of our own slow apocalypse.

-Ian Mond

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the November 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.