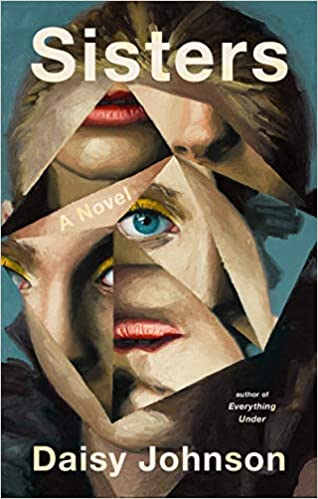

Ian Mond Reviews Sisters by Daisy Johnson

Sisters, Daisy Johnson (Riverhead Books 978-0-593-18895-8, $26.00, 224pp, hc) August 2020.

Sisters, Daisy Johnson (Riverhead Books 978-0-593-18895-8, $26.00, 224pp, hc) August 2020.

In my review of Sophie Mackintosh’s second novel Blue Ticket, I noted that her first book, The Water Cure, was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2018. The other debut novelist who snagged a Booker nomination that year, getting as far as the shortlist, was Daisy Johnson with Everything Under, a gender-fluid retelling of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, set amongst the waterways and flood plains of eastern England. I adored Everything Under – the gorgeous language, the exploration of memory and sexual identity, and the mythical overtones in the shape of the fearsome ”Bonak.” While I’ve since regretted not reviewing the book for Locus – making up for this slightly by including Everything Under in my yearly round-up for 2018 – I knew I wasn’t going to make the same mistake with the publication of Johnson’s second novel, Sisters.

What I particularly loved about Everything Under was Johnson’s distinctive voice, especially the thought and care that went into each sentence. Thankfully, that same appreciation for language is evident from the opening paragraph of Sisters. Johnson skillfully evokes a sense of unease, as a mother (Sheela) and her two teenage daughters (July and September) arrive at a ”dirty white” house (The Settle House) ”beached up on the side of the North York Moors, only just out of the sea.” Why they’ve left Oxford – where Sheela enjoyed some success as the author of a series of children’s books starring both her daughters – for the remote beaches of North Yorkshire is not made immediately apparent. All we know is that the daughters have done something wrong, with July observing that her mother has been ”taciturn or silent, ever since what happened at school.” It’s a tantalising set-up: the ramshackle, abandoned house located beside the sea, with its walls streaked with mud and ”broken tiles from the roof shattered on the road;” the hints and whispers of a tragic event in the past, one that’s left a mother distraught, barely able to meet the eyes of her daughters; and the two sisters, July and September, who, while not twins (they are a year apart), have a bond so tight, so intimate, they can almost read each other’s minds.

I’m sure I won’t be the only reviewer to get a strong Shirley Jackson vibe from Sisters, particularly in connection with We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Both novels feature two sisters in an isolated setting (including a large house that has seen better days) with oblique references to a tragic event (until a major reveal toward the end) that forces the siblings (together with their Uncle or Mother) to remove themselves from the community. Just like We Have Always Lived in the Castle, where the story is told from the unreliable perspective of 18-year old Merricat, Sisters is built around July – the younger of the two sisters – whose recollection of events also can’t entirely be trusted. Even the two chapters from Sheela’s point of view, which cut through the ambiguities and misdirection presented by July, recall Uncle Julian’s attempts to explain what happened to the Blackwood family. Where Johnson differs from Jackson is how she portrays the central relationship between the two sisters: Johnson charts a much darker, more difficult path than Jackson does with Constance and Merricat (and that’s saying something). July is undoubtedly devoted to September (particularly her protective nature acting as a ”sleep shadow” when July begins to sleepwalk: ”[September] would be there, hushing me as I woke already screaming”) or defending July from school bullies. But even as July underplays the more troublesome aspects of her sister, it’s clear to the reader that September enjoys a perverse thrill from harming July. Her twisted version of Simon Says, September Says, is indicative of the control September has over her sister (”I was the puppet and had to do whatever she said”), and regularly ends with July self-harming (”[September Says] put this needle through your finger”). What makes it all the more horrible (I’m being opaque to avoid spoilers) is that rather than confront her sister’s cruelty, July leans into it.

Beyond the psychological trauma July experiences at the hands of her sister, beyond the tumbledown house, a metaphor for the fractured, tortured minds that live within, beyond the unspoken tragedy that haunts every page of the novel, is the astonishing prose. Johnson’s impressionistic style leans heavily on imagery rather than detail, often twisting the ordinary and mundane out of shape. There’s one brief, but extraordinary passage where July describes the multitude of birds that surround the Settle House, noting that ”There is something black and monstrous moving through the stalks, rushing back and forth, making a catastrophe of noise.” That sensation of something lurking in the darkness, something out of sight, but so very present, is an effect that Johnson sustains throughout Sisters. It culminates in a revelation that caught me off guard (even though I should have seen it coming), a moment of clarity that only deepens Johnson’s complex, harrowing portrayal of love and abuse.

This review and more like it in the July 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.