Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Big Girl by Meg Elison

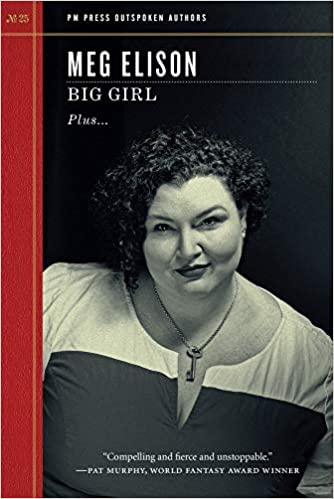

Big Girl, Meg Elison (PM Press 978-1-62963-783-9, $14.00, 128pp, tp) June 2020.

Big Girl, Meg Elison (PM Press 978-1-62963-783-9, $14.00, 128pp, tp) June 2020.

Meg Elison seemed to come out of nowhere when her 2014 novel The Book of the Unnamed Midwife earned the Philip K. Dick Award, and her short fiction output has remained relatively sparse (although the novel did see two well-received sequels), so Big Girl, her contribution to the long-running ”Outspoken Authors” series from PM Press – a series mostly known for eclectic samplings of well-established authors as varied as Ursula K. Le Guin and Karen Joy Fowler – might serve well as an introduction to her work, as it did for me. What this collection – three essays, three stories (two of them original), and the usual quirky interview with series editor Terry Bisson – shows is a voice that is at once affable yet angry, sharply satirical yet humane, visceral yet carefully controlled. The most consistent theme in these pieces, broadly speaking, is size: not simply the personal issues of weight and body image that are the focus of the longest story here, ”The Pill”, and the insightful concluding essay ”Guts”, but the broader issue of what we might simply call appropriateness of scale. That may be one reason that the collection opens with a kind of memoir, ”El Hugé”, which involves those giant-pumpkin growing contests that seem to show up in the news every fall, monstrosities with ”no beauty, only bigness.” The 1,200-pound giant of the title ”was somehow inexcusably offensive” to the narrator and her teenage friends, who basically kidnap it in a scheme that, inevitably, doesn’t work out as planned. This is followed by ”Big Girl”, a story which originally appeared in F&SF. Cast in documentary form, it describes Bianca Martinez, a 15-year-old girl who wakes up one morning near San Francisco Bay, finding herself 350 feet tall. The story is largely a satire of media hysteria – she’s an art installation, a giant sex doll, etc. – but quickly raises deeper issues of civil rights and privacy. As she begins to shrink from her immense size, is there a point at which her body becomes ”acceptable?” The tale recalls the pointed absurdities of a story like Kit Reed’s similar ”Attack of the Giant Baby”, and even though the metaphor risks becoming a bit schematic, at least Elison avoids invoking old chestnuts like Attack of the 50-Foot Woman.

Considerably darker is the original novella ”The Pill”, which very nearly succeeds in turning weight loss into body horror, but not in the way you might think. The drug of the title is a kind of miracle treatment which essentially causes the body to excrete fat cells and even excess skin in a pretty disgusting and effective but risky way. The narrator’s mother is an enthusiastic early adopter, but when her father becomes one of the ten percent of the drug’s fatalities, the narrator herself resists, even as the drug (despite its mortality rate) becomes so ubiquitous that overweight people risk losing basic civil rights, or even insurance coverage. The unlikely accommodation she eventually discovers seems to offer some respite from this emerging dystopia – which, with its enforced body-conformity, recalls earlier novels from L.P. Hartley’s Facial Justice to Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies – even though it unbalances the story’s tone a bit. A painful toothache introduces us to the even bleaker world of ”Such People in It”, a Trumpian nightmare of a society ruled by ”Decencies” under an unnamed president who, after eleven years in office, still boasts of achieving ”Peace like my weak predecessors never could have achieved. We have incredible peace, peace like no other. And you know why we have that? Because America is great again.” If it sounds familiar, that may be because it’s an almost unmediated version of nightmares a lot of us were actually having back in 2016.

The two remaining non-fiction pieces are both brilliant and deeply honest, but in very different ways. ”Guts” describes the decision of Elison’s mother to undergo surgical intervention ”because she was tired of the inescapable fight that is life in a fat body,” of ”other people I knew who moved out of their bodies,” and of Elison’s own decision, instead, to ”seek out ways to weaponize my own image.” ”Gone with Gone with the Wind” describes her early passion for Margaret Mitchell’s novel, which she reread obsessively, first seeing Scarlett O’Hara as an exemplar of the resourceful woman survivor, but later as a brat blind to her own inherited privilege, and still later as an emblem of whiteness and institutionalized racism. It’s at once an acknowledgement of the magnetism of Mitchell’s main character and of the dangers of that magnetism, but mostly it’s an exemplary essay on the art of rereading and coming to consciousness. Both in fiction and non-fiction, Elison is clear-eyed, unsentimental, funny, furious, and exactly the sort of ”outspoken author” that this PM series seeks to celebrate.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the July 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.