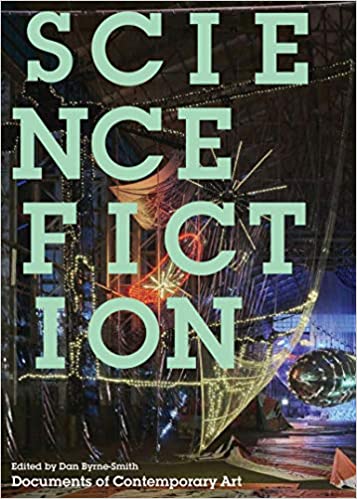

Alvaro Zinos-Amaro Reviews Science Fiction: Documents of Contemporary Art, Edited by Dan Byrne-Smith

Science Fiction: Documents of Contemporary Art, Dan Byrne-Smith, ed. (The MIT Press 978-0262538855, $24.95, 240pp, pb) April 2020.

Science Fiction: Documents of Contemporary Art, Dan Byrne-Smith, ed. (The MIT Press 978-0262538855, $24.95, 240pp, pb) April 2020.

The question of who the intended readership is for the non-fiction anthology Science Fiction, edited by Dan Byrne-Smith for the Documents of Contemporary Art MIT Press series, kept nagging at me throughout. The series, we are told, focuses on subjects ‘‘of key influence in contemporary art internationally’’ and seeks to provide access ‘‘to a plurality of voices and perspectives defining a significant theme or tendency.’’ That’s certainly a wide remit. How does it apply to genre? Well, in his introduction, Byrne-Smith says he hopes ‘‘to challenge the idea that science fiction can only be thought of as genre. Instead science fiction can be forms of practice, complex networks, or a set of sensibilities. It can be thought of as a field, a space of metaphor or a methodology.’’ The present volume is comprised of 48 essays and conversations, all reprinted material (save for two original texts) ranging from 1962 through 2020, organized into four sections: Cognitive Estrangement, Futures, Posthumanism, and Ecologies. Byrne-Smith’s eloquent Introduction may well be, at least as a self-contained unit, one of the volume’s most successful entries – with trenchant observations like ‘‘reciprocal glances have long since been exchanged between the worlds of surrealism and science fiction,’’ and one which casts a semblance of cohesion on the dozens of reprints that follow.

Let us sample its flavors. Early on, an excerpt from Margaret Atwood’s Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination (2011) attempts to shed light on matters of genre definition: ‘‘In short, what Le Guin means by ‘science fiction’ is what I mean by ‘speculative fiction,’ and what she means by ‘fantasy’ would include some of what I mean by ‘science fiction.’ So that clears it all up, more or less.’’ Atwood claims that Nineteen Eighty-Four isn’t ‘‘as much’’ science fiction as The Martian Chronicles, which is like adding silt to muddy waters in the interests of purification. To be fair, though, Byrne-Smith warns that discussions of definition in the book ‘‘are not resolved.’’ Following Atwood, Gilane Tawadros & John Gill write about an exhibition of 12 international artists titled ‘‘Alien Nation’’. Since we can’t see it (this happens repeatedly), we must conjure it up using our own mental gifts of extrapolation. Reading about installations like Yinka Shonibare’s Dysfunctional Family, Ellen Gallagher and Edgar Cleijne’s Murmurs, and many other exhibits without experiencing them does produce estrangement – just not of the cognitive variety that Byrne-Smith champions.

In an excerpt from his oft-cited Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (1979), Darko Suvin notes that ‘‘although SF shares with myth, fantasy, fairy tale and pastoral an opposition to naturalistic or empiricist literary genres, it differs very significantly in approach and social function from such adjoining non-naturalistic or meta-empirical genres.’’ He then argues that our genre ‘‘has always been wedded to a hope of finding in the unknown the ideal environment, tribe, state, intelligence, or other aspect of the Supreme Good (or to a fear of and revulsion from its contrary).’’ If so, and if we are to judge by the rest of the book’s contents, the hope is a Sysiphean one. Sherryl Vint makes astute observations about Suvin’s work, particularly when she reflects that ‘‘Suvin sets himself a difficult challenge, dismissing as ‘perishable’ at least 90% of what was published under the label SF at the time, defining the genre not by its ‘empirical realities’ but according to its ‘historical potentialities.’’’

When Roger Luckhurst presses digital artist and avataristic time-traveler Suzanne Treister for epistemological clarity around her work, she replies: ‘‘True or false is not the point. All the information in my work is on one level or another true. There is no invention, just re-presentation. There is so much recent art commentary rhetoricising this supposedly fascinating blurry area between fact and fiction. These people are missing the point. It’s an academic fence-sitter position. There is no fence. Nowhere is a fence. There is only exposure of the horror and the joy, and the bits in between but there are no fences.’’ Is that too long for a T-shirt? How about maybe just ‘‘There is no fence’’?

Carrie Paterson refers to Philip K. Dick as ‘‘the original paranoid genius who taught us the poetry of coincidences,’’ a phrase we would do well to preserve in our commonplace books. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi suggests ‘‘a new form of wisdom: harmonising with exhaustion.’’ I like the sound of that, but what does it mean? Isn’t exhaustion a breaking of whatever equilibrium is established by harmony? ‘‘The future is over,’’ continues Berardi, culminating in a comparatively concrete prescription: ‘‘We are living in a space that is beyond the future. If we come to terms with this post-futuristic condition, we can renounce accumulation and growth and be happy sharing the wealth that comes from past industrial labour and present collective intelligence.’’ The past surfaces in other ways too. Case in point, the text penned by N.J. Stallard for a 2018 exhibition in the London Danielle Arnaud Gallery, on E.M. Forster’s perennial ‘‘The Machine Stops’’. Benjamin Noys writes about ‘‘cyberpunk fiction, Detroit techno, and their synthesis in Cybertheory.’’ If you want to follow along, get ready to dust off your copy of Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus (1972). Dawn Chan, in a piece about Asia-Futurism, laments that ‘‘the relative invisibility of Asian people in America often seems refracted throughout international contemporary art exhibitions’’ and expounds on the implications of this state of affairs. Jamie Sutcliffe, in a complementary article, describes his experiences with Asia-Futurism at The Uni- verse and Art exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in the district of Roppongi, Tokyo. Ana Teixeira Pinto covers a variety of ‘‘futurisms,’’ including Italian, Sino- and Gulf-.

Donna J. Haraway’s ‘‘A Cyborg Manifesto,’’ with its remark that cyborgs move beyond ‘‘bi-sexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour,’’ remains as relevant today as when first published, but also preserves matters of import in the 1990s. N. Katherine Hayles intriguingly likens the Turing Test to a magic trick, and in the context of post-humanism, Jeffrey Deitch succinctly captures one of science fiction’s central preoccupations in the twenty-first century: ‘‘Our consciousness of the self will have to undergo a profound change as we continue to embrace the transforming advances in biological and communications technologies.’’ Francesca Ferrando’s ‘‘A Feminist Genealogy of Posthuman Aesthetics in the Visual Arts’’ covers much ground, and I wish it had been awarded more than a two-page excerpt. Elizabeth C. Hamilton’s ‘‘Afrofuturism and the Technologies of Survival’’ probes a series of fascinating-sounding works by diverse artists and poignantly concludes that for them the black body ‘‘is fragile, permeable and under attack.’’

In the section on Ecologies, a brief Rachel Carson snippet is followed by a Kim Stanley Robinson interview with Helena Feder, one of the volume’s most rewarding dialogues. Another substantial conversation, by Ama Josephine Budge and Angela Chan (this is one of the book’s two original texts), is peppered with commendable references to recent non-Anglocentric science fiction. In a long piece titled ‘‘Gardening Against the Apocalypse’’ T.J. Demos offers an ecologically minded call to action: ‘‘In the present age of crises and emergencies, we need bold proposals, not fuzzy non-concepts.’’ Some of this book’s contributors, I suspect, would prefer esoteric theorizing to the Occupy movement to which Demos refers. The volume concludes with its second original contribution, David Musgrave’s critical discussion of Kobo Abe’s Inter Ice Age 4 (1959), an assessment contextualized by Abe’s ‘‘own disparagement of prediction.’’

Whew. And that’s but a small sampling of the dozens of aperitifs on offer, which returns us to the question of Science Fiction’s audience. Casual readers interested in the history of science fiction or even a discussion of its theoretical fundaments would be better served by a variety of other texts. Academics performing research will more profitably consult the primary sources here cited (or follow up on the profuse end-notes appended to each piece), and will likely find this book’s expansive purview and sweeping ambition contrary to the kind of specialization usually helpful in their endeavors.

It strikes me that this volume, with its consistently fragmentary and evocative nature, might qualify for inclusion in its own pages: it is, after all, a kind of found object of science fiction scholarship, suggesting many avenues of artistic pursuit without committing to a specific one. Science fiction publishing used to regularly produce so-called ‘‘fix-ups,’’ novel-like assemblies of previously published and interrelated stories, sometimes epoxied with new material. Is this SF’s first non-fiction fix-up? Perhaps we should be more generous and consider the art of kintsugi, or Japanese pottery mending. Imagine using kintsugi not to restore an individual object, but to creatively meld together disparate ceramic shards from different epochs, and thus fashion a lacquerware amalgam with its own distinctive, a-temporal identity. Brokenness, it may be said, has its own beauty.

This review and more like it in the July 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.