Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Song for the Unraveling of the World by Brian Evenson

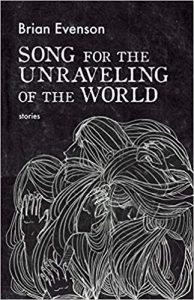

Song for the Unraveling of the World, Brian Evenson (Coffee House Press 978-156689-548-4, $16.99, 212pp, tp) June 2019.

Song for the Unraveling of the World, Brian Evenson (Coffee House Press 978-156689-548-4, $16.99, 212pp, tp) June 2019.

In his story “Leaking Out”, which could be read as Brian Evenson’s characteristically oblique take on the haunted house tale, a “malformed man” (another characteristic Evenson figure) starts telling a story with the warning that “this is not that kind of story, the kind meant to explain things. It simply tells things as they are, and as you know there is no explanation for how things are, at least none that would make any difference and allow them to be something else.” It’s as good a gloss as any to describe the narrative strategies of the 22 tales in Song for the Unraveling of the World, most of which begin by laying out a mystery or anomaly, which may or may not get resolved in terms of horror or SF, or in terms of Evenson’s own peculiar brand of post-New Weird strangeness. Obviously, it can be difficult to assign labels to an author whose playlist seems equally comfortable with Kafka, Raymond Carver, or Cormac McCarthy on the one hand, and Lovecraft, Matheson, and Dead Space on the other (Evenson wrote a couple of novels in that franchise).

Often those initial puzzles or mysteries involve mundane oddities that recall a long tradition of short weird fiction that we used to see everywhere from John Collier and Shirley Jackson to Jack Finney to Matheson (who I suspect is largely responsible for introducing this sort of sensibility to The Twilight Zone, which also came to mind in a couple of cases here). A man finds items mysteriously disappearing from his new apartment in “Menno”, which leads to an increasingly irrational obsession with his neighbor. A magic act seems to go horribly awry in the short-short “Cardiacs”, while a new pair of glasses from a mysterious drugstore reveals a shadow-like creature in “Glasses”. The faceplate of an astronaut’s helmet seems to reveal a kind of presence undetectable by the ship’s sensors in “Smear”, one of a handful of clearly SF/horror tales. Rask, the central character in “Wanderlust” (Evenson likes quirky, not quite traceable names), grows obsessed with the feeling he’s being watched, and (in one of the more conventional narrative twists) eventually learns who the watcher is. Similarly, in “The Glistening World”, a woman searching for her missing girlfriend becomes convinced she’s being followed by a faceless man in a gold suit, who turns out to have had an unexpected purpose as she learns the girlfriend’s fate.

With its missing girlfriend, “The Glistening World” is also an example of how Evenson employs the conventions of crime fiction. The title story begins with Drago frantically searching for the daughter who has suddenly disappeared, but unfolds in a chilling way as we learn more about Drago. The missing figure in “A Disappearance” is a wife, but as the narrator (one of the few first-person voices in the book) reveals more about what actually happened, the tale grows disturbingly darker. Another first-person narrator, in “Kindred Spirit”, might have prevented a sister’s suicide, but in this case, as we learn more about the narrator, the tale resolves in the direction of SF. By far the strongest SF story here is “Lord of the Vats”, which seems to draw on Evenson’s experience with Dead Space, with Lovecraftian overtones, in describing the grim fate of the crew of a damaged spaceship.

Several of Evenson’s settings actually have more in common with the bleak, anonymous landscapes of an author like Samuel Beckett (more the novels, like How It Is, than the plays). In “The Second Door”, a brother and sister (sisters are a recurring theme) are trapped in a cylindrical room that looks a lot like a spacecraft, but with only two doors, one opening on a barren plain and the other on sheer darkness. Figures in “The Tower” struggle though a devastated urban landscape toward a mysterious structure that may save or kill them. A spaceship crew exploring an almost featureless gray planet faces a crisis when one of them disappears into “The Hole” and emerges changed.

As eclectic as these stories may be, there are enough recurrent preoccupations that the collection as a whole provides a solid overview of Evenson’s unique imagination. He’s fascinated by liminal states, figures who are not quite alive and not quite dead (“The Tower”, “The Hole”, “Lord of the Vats”), figures who are doubled by shadow selves (the psychotherapist in “Born Stillborn”, the sister in “Kindred Spirits”, Rask in “Wanderlust”), figures who become so obsessed with minor details that it begins to consume their lives (as in “Menno”). The latter is most evident in the three stories that deal with filmmaking: “Room Tone” describes a director convinced he needs extra footage to capture the “room tone” of a house he’s no longer permitted to film in, leading to a deranged act, while in “Line of Sight” another director grows convinced the eyelines are wrong in his new film, even though everyone loves it. It’s really an ingenious horror story about the terror of things going too well. “Lather of Flies”, about a young film scholar trying to track down a legendary lost film by a famous director, also turns into a sort of mordant horror tale. Horror is the genre most allied with Evenson’s sensibility – even the SF tales, as I noted, are essentially SF horror – but at the same time it would be misleading to imply that horror can contain him. If I were asked to describe the overall range of Evenson’s darkly comic imagination in one word, it would be “uncontainable.” Sometimes the risks he takes don’t quite pay off, and sometimes they pay off in familiar ways, but often they take us into intriguing if uncomfortable spaces where we’ve never been. Evenson’s stories can’t quite be said to occupy the genres that they play with, but genres occupy the stories, and he ties them into elegant little knots.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the June 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.