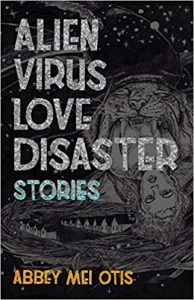

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Alien Virus Love Disaster by Abbey Mei Otis

Alien Virus Love Disaster: Stories, Abbey Mei Otis (Small Beer 978-1-618-73140-1, $16.00, 238pp, tp) August 2018.

Alien Virus Love Disaster: Stories, Abbey Mei Otis (Small Beer 978-1-618-73140-1, $16.00, 238pp, tp) August 2018.

As I’ve mentioned before, the better small presses cultivate a curatorial sensibility, a distinct personality which can be a reliable indicator that, whatever this new book is, it’s probably at least interesting. Small Beer Press is near the top of this list, and Alien Virus Love Disaster is a good example of what they do best. I confess to having read nothing at all by Abbey Mei Otis, but that may be because some of the stories collected here appeared in such venues as Tin House or Story Quarterly, though a couple are from Strange Horizons and Tor.com. That places her in the company of an increasing number of short fiction writers who move comfortably between more traditional high-literary hipsterism and street-level genre, and who are equally comfortable deploying the materials of SF/F in stories whose real focus sometimes lies elsewhere. There are, to be sure, aliens in these tales, along with sex robots, immigrants from the Moon, ghosts, odd creatures, and virtual realities, but the themes that Otis returns to – families, home vs. work environments, love, class distinctions, fragile communities, decadent wealth and decaying suburbs – are entirely her own. The title story, for example, does indeed feature a disaster in which a secretive government laboratory contaminates the adjoining town, resulting in strange bodily growths on the local population and eventually on the abrupt evacuation of the entire town, all apparently resulting from experiments involving alien material that landed on Earth sometime earlier. The focus, however, is on the narrator and her younger brother Dean as they and their neighbors try to cope with the effects of such a strange metamorphosis on their daily lives; the only hints we get at an SFnal explanation come from a guilt-ridden scientist who once worked at the facility – which has by then been wiped from all records as though it never existed.

A couple of the stories are set in a vaguely dystopian world of failing suburbs which “had been spiraling down for sixty years” and are filled with abandoned half-built houses or houses already in decay. In “If You Could Be God of Anything”, a sex robot literally falls from the sky into the lives of the narrator and her brothers, while in “Ultimate Housekeeping Megathrill 4” – one of the strongest stories here – a mother with an oppressive job at a quality-control conveyor belt comes home and logs into a VR system that takes her not into a world of fantasy adventures, but simply into a more pleasant version of her own life – while her kids, facing a medical crisis, try desperately to bring her back to reality. The narrator of “Sex Dungeons for Sad People” works at night as a kind of living sex-doll encased in and protected by a latex sleeve, but in daytime is a seventh-grade teaching assistant at an alternative school located in an abandoned strip mall. Suya, the narrator of “Rich People” lives in a similarly decrepit apartment, along with her mother, a man, and a baby (not hers), but manages to escape by crashing a surrealistically decadent party of the ultra-rich, who entertain themselves by decorating the hundreds of roasted chickens on the buffet or by slicing open animal carcasses and crawling inside, something like Gatsby reimagined by Luis Buñuel.

Actual aliens show up in “Blood, Blood”, in which the teenage narrator and her friend George find they can make substantial money simply by staging fights in front of the alien visitors (actually disembodied avatars). It’s not as though the aliens – who have brought health and prosperity with their advanced technology – are especially bloodthirsty; they’re also fascinated watching people eat French fries or work a supermarket checkout. “Sweetheart”, the shortest story here, depicts a 6-year-old who befriends an insect-like alien visitor, only to confront the loss of his friend because of an irrational backlash against the (again quite helpful) aliens. Otis has a little fun with her own preoccupation with aliens in the very title of “Not an Alien Story”, although again it involves a strange creature discovered by a group of young people in a flooded, post-global-warming world. The “Moonkids” in the story of that title aren’t quite aliens – they’re exiles from an elite Moon colony who have failed to pass tests required to remain there – but they get treated as aliens as they try to get jobs back on Earth.

Not all the stories foreground SF machinery, though. “I’m Sorry Your Daughter Got Eaten by a Cougar” is set in a sparsely populated valley in which, indeed, a local daughter has been killed by a cougar, but the narrator has her own problems with the ghost of a man dead 200 years. The Shirley Jackson-flavored “If You Lived Here, You’d be Evicted by Now” begins with a family returning home to murder their mother, in order to hold on to the property, which might otherwise be converted to a “trading post” because of some mysterious regulation. The tone of these tales is of a piece with Otis’s highly original style, characterized by a kind of mordant humor underlying a rather grim and diminished world in which, as a character in “Not an Alien Story” says, “Things aren’t going to change. We aren’t going to get jobs. Animals aren’t going to pad through our dreams and whisper the answers.” Sometimes Otis can toss off a classic Kelly Link-style sentence (“She was so rich the stories came true as she spoke them”), sometimes an almost pulp-like opening hook (“Can’t remember if I was nine or ten when the sex robot fell from the sky”), sometimes a sharp apothegm about the appeal of VR (“It’s not that planet calling you. It’s this one pushing you away”). If Otis’s overall vision seems pretty dark, it’s ameliorated by the colorful voices and deeply humane characters struggling in a world that offers them plenty of bizarre experiences, but little real hope. It’s a world far more like ours than we’d want to believe, but it also a world not quite like anyone else’s. At their best, the stories in Alien Virus Love Disaster can generate the same sort of excitement of first coming across writers as diverse as Kelly Link, M. Rickert, or Margo Lanagan: a striking new voice, both strangely familiar and yet disorienting, that takes us somewhere we haven’t been.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the July 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.