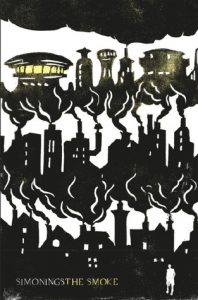

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The Smoke by Simon Ings

The Smoke, Simon Ings (Gollancz 978-0-575-12007-5, £16.99, 298pp, tp) February 2018.

The Smoke, Simon Ings (Gollancz 978-0-575-12007-5, £16.99, 298pp, tp) February 2018.

Simon Ings’s The Smoke – his second new SF novel in four years after having taken more than a decade off for more mainstream projects (including a fascinating study of science under Stalin) – is quite a bit more radical than 2014’s Wolves, which was judiciously and elegantly restrained in its examination of the possible impact of augmented reality, but it shares with that novel a deep focus on character that at times hardly seems to need the SF armature at all. One of the most compelling and beautifully realized chapters, in fact, is a dinner party which the protagonist and part-time narrator Stuart Lanyon, an aspiring architect, attends with his working-class father Bob, his brother Jim (an astronaut in training who hopes to become the first Yorkshireman in space), his brilliant girlfriend Fel, her wealthy and powerful physician father Georgy, and Georgy’s companion Stella, who is trying to develop a rather cheesy-sounding TV series about alien invasions on the moon (Ings mentions Gerry and Sylvia Anderson in the acknowledgments). Stella, in turn, is Stuart’s own aunt – the sister to his mother Betty, who is dying of cancer. The tensions of class and privilege, of generations, of conflicting aspirations, and of family dynamics would be at home, and just as impressive, in any number of mid-20th-century British novels of domestic realism. But before we even get to this point, Ings has placed these characters in a radically defamiliarized setting that only magnifies those classic tensions in a kind of distorting mirror. By the time we’re done, we’ve gotten ourselves into a complex stew of alternate history, mid-1950s SF dreams (not just the TV show, but a version of the Orion atomic spaceship project), class distinctions turned into biological processes, a very weird form of life extension biotech, and maybe even a war with the moon.

Early on, we are given to understand that the “Great War” ended in 1916 with the nuking of Berlin and the irradiation of Europe, that a Yellowstone Eruption in 1874 devastated North America and led to a decade-long global winter, and that – more to the immediate point of how this world diverged from ours – the real-life Russian embryologist Alexander Gurwitsch perfected a “biophotonic ray,” which led to a form of biotech that eventually led to “the speciation of mankind.” Not too surprisingly, that speciation tended to fall along class lines in a way not too different from those in Wells’s The Time Machine, but much more rapidly, and with more catastrophic results. At the top of the sociobiological heap is an enhanced class of urbanites call the Bund, who have taken over large swaths of London (usually referred to as “the Smoke”), and whose advanced technology has already sent robot miners to the moon. Ordinary, “unaccommodated” humans (for which we might as well read Yorkshiremen, given the setting) constitute a kind of lower middle class, with its own more bluntly industrial approach to space exploration represented by the Orion-style spaceship being constructed in Australia. A species of despised smaller “sub-humans” called Chickies, an unfortunate mutational aftereffect of the Great War, in some ways recall Margaret Atwood’s “Crakers” in that they cast a kind of sexual spell over humans. As we learn from a clever and unexpected point-of-view shift in the novel’s opening section, though, they aren’t quite as inarticulate or subhuman as they might at first seem.

That point-of-view shift represents another somewhat risky decision on Ings’s part. Like many, I find that second-person viewpoints, outside of epistolary tales, can be pretty annoying unless managed carefully – we never know up front if the narrator is speaking to the reader, to another character, or to themselves, and it can quickly begin to feel like an excessively coy game of hide-and-seek. Ings sustains this for most of the first two chapters, including most of the background information mentioned above, but then shifts almost seamlessly to a first-person viewpoint whose nature I should not disclose here. The novel’s second and longest section is a more conventional first-person narration by Stuart, and separate italicized passages outside the main narrative detail the experiences of Stuart’s astronaut brother Jim, in what amounts to a fairly conventional space-disaster tale of its own.

For all the inventiveness of the alternate UK presented here, the novel’s greatest power derives from Stuart’s own narration – his own insecurity at why the brilliant and enhanced Fel should want to be with him, the classic Lawrencian tension between his architectural and social ambitions and his working-class dad, the compromise of those ideals by agreeing to design sets for his aunt’s tacky SF TV series (which is described in such detail that Ings is clearly having fun with it), and his helplessness at his mother’s debilitating disease. But the mother, Betty, also comes to represent the intersection of SF ideas and character dynamics in a way that most of the novel only implies. That doctor, Georgy Chernoy, the paramour of Stuart’s aunt and the father of his girlfriend, has developed a medical procedure which seems to promise a kind of immortality, but at the cost of having the patient’s mind downloaded into that of a rapidly growing infant, who needs to learn motor skills and re-orient to the world in order to make those memories functional. When Betty becomes one of these new children – over her distraught husband’s fierce objections – the result is a surrealist nightmare and a Freudian dream: Stuart facing the prospect of changing his infant mom’s diapers, the mom screaming Yorkshirewoman invectives in the voice of a toddler, the father hopelessly unable to deal at all. As convincing and insightful as the family drama is on its own terms, situations like this remind us that Ing could not have told this haunting tale without the SF, and he couldn’t have told it with only the SF. It’s a classic example of how SF need not be in opposition to the traditional template of domestic realism, but can amplify it exponentially.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the May 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.