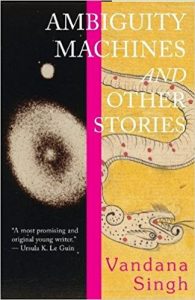

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories by Vandana Singh

Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories, Vandana Singh (Small Beer 978-1-618-73143-2, $16.00, 336pp) February 2018.

Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories, Vandana Singh (Small Beer 978-1-618-73143-2, $16.00, 336pp) February 2018.

For the past 15 years or so, Vandana Singh has been producing consistently interesting and often brilliant short fiction, and her name is often among those mentioned in celebrations of SF’s growing diversity. But “diversity” can have a number of meanings, and, as beautifully demonstrated in her new collection Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories, diversity in Singh’s fiction is more complex than simply her identity as an Indian-born writer or her day job as a physics professor. For one thing, her characters are often middle-aged or older women, a fairly underrepresented group in SF, while others may be poor or uneducated, or even dead (the narrator of “Somadeva: A Sky River Sutra” is an 11th-century Indian poet re-created to accompany a space explorer out to collect myths and legends from various worlds). Her themes are less likely to focus on romance and adventure than on compassion and loss – and yet she often makes use of familiar space opera tropes and settings, as well as of classically hard-SF speculations about physics or information theory. And she’s clearly interested in a degree of formal experimentation, with stories embedded or interleaved in other stories, shifts in points of view, and voices that at times seem deliberately contrapuntal.

The title story, for example, is framed as a prompt for exam candidates in the “Ministry of Abstract Engineering,” where they study “Conceptual Machine-Space, which is the abstract space of all possible machines.” This sounds like an engineering version of Borges’s Library of Babel, but the three vignettes which comprise the bulk of the story are anything but abstract in human terms: one involves a prisoner who, when asked to develop a new weapon, instead constructs a machine that will reveal his lover’s face; in the second a mathematician disappears while trying to understand a mysterious courtyard in Italy; the third features an archaeologist who discovers a hidden settlement near Timbuktu which seems to “blur the boundary between the self and other.” These are related not only because they are all “ambiguity machines” on the boundary of possible and impossible, but through certain recurring images, such as a broken tile. As a meditation on the synergy between the possible and the impossible, the story also becomes a subtle comment on the related narrative spaces of SF and fantasy.

Most of the stories, though, are pretty clearly science fiction – although the relationship of SF to fantasy does come up again. “Oblivion: A Journey” takes the form of a fairly straightforward revenge space opera, but the narrator, an “interplanetary investigator” obsessed with tracking down the villain, finds the model for her own story in the Indian epic the Ramayana. Isha, the space explorer in “Somadeva: A Sky River Sutra”, not only recreates that 11th-century poet as her companion, but is fascinated with collecting origin myths and stories from the planets she visits, and several such stories are interpolated in her own. “Ruminations in an Alien Tongue” begins with the very mainstream premise of an old woman remembering past loves, but places it in the context of an alien race who mysteriously disappeared, possibly with the help of an “actualizer,” a device which alters probabilities, “opening a path to a universe just like this one, but with your personal parameters adjusted ever so slightly” – in other words, another sort of ambiguity machine, but one which resonates with the woman’s own reconsiderations of her past. The other deep-space story, “Sailing the Antarsa”, features some of the most traditional SF tropes – a planet colonized by a generation ship has lost touch with a sister ship bound for another world, and now the narrator is en route to solve the mystery. Eight years into her voyage, she’s awakened prematurely by the ship’s AI, and later finds herself accompanied by what appear to be alien ships. The story is rich in invention, from the details of her ship itself to the bold notion of the Antarsa, an invisible current which “washes through planets and stars, plants and people, as though we did not exist” – but to which a form of matter called “altmatter” is opaque, and thus able to ride it like a current. What makes the story one of the strongest in the collection is the narrator’s memories of her past lovers and of mythlike tales from her childhood, especially a fable about a young girl’s relation to nature in the form of a sort of supertree.

Some of the other stories also invoke more traditional space opera notions of competence, such as “Life-Pod” and “Wake-Rider”, but Singh is also capable of what approaches straight-up horror in “Are You Sannata3159?”, set in a desperate and grimy undercity below the huge towers in which the privileged live. The fact that the most prominent institution in the young protagonist’s world is a slaughterhouse is enough to set the tone for a devastating ending. This acute awareness of class divisions, along with themes of family and memory, is another of Singh’s trademarks, and it’s nowhere more evident than in her excellent lead story, “With Fate Conspire”, which involves another rather familiar SF device, a machine through which specific moments of the past can be viewed but not influenced. Only a very few with a specific brain abnormality can interface with the machine, and the narrator, assigned to observe an exiled poet in 19th century Kolkata, is a poor refugee who is virtually a captive of the scientists. But instead of the poet, she becomes fascinated with a housewife from the same time and place, and begins to manufacture her reports about the poet, whom she’s not even watching. There’s a rather neat twist involving time loops toward the end, and whether they can be created from the future, but the most compelling aspect of the story is the notion of the anonymous observer discovering her own story. Story, in fact, and how we are defined by it, is really Singh’s grand theme, and while her sophisticated narrative choreography may give some readers pause – since her tales often begin with classic SF tropes and then move elsewhere – it’s what makes her one of the most compelling and original voices in recent SF.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the February 2018 issue of Locus.