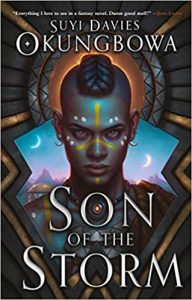

Maya C. James Reviews Son of the Storm by Suyi Davies Okungbowa

Son of the Storm, Suyi Davies Okungbowa (Orbit US 9780316428941, $14.49, 480pp, tp) May 2021.

Son of the Storm, Suyi Davies Okungbowa (Orbit US 9780316428941, $14.49, 480pp, tp) May 2021.

Note: Son of the Storm refers to very light-skinned Africans (i.e. “high yellow”) as “yellowskin.” It refers to people with albinism and not people of Asian descent (all characters are of African descent in this novel).

Forbidden knowledge, half-truths, and a woman with magic that is not supposed to exist. Son of the Storm is an immaculate and intelligently crafted West-African-inspired epic fantasy from Suyi Davies Okungbowa. Told from multiple points of view, we follow the journey of Esheme, Danso, and Lilong as they bear witness to the atrocities of the Bassa Empire and unravel the lies it has been built upon.

First in the Nameless Republic series, Son of the Storm begins with Danso, a talented jali, or scholar, who straddles different castes. Unfocused and too intelligent for his own good, we encounter him at the beginning of his journey, where he starts to notice inconsistencies and large swaths of missing information about the Bassa Empire in his studies. His curiosity is not quelled, even after he is punished for reading a codex of forbidden information that contradicts everything he has been taught. The mythical “yellowskins” intrigue him in particular. They are skin-changers from a long-gone archipelago who are not supposed to exist, but supposedly have body parts with magical healing properties (a dangerous, real-world myth about people with albinism that persists today). The skinchangers also use ibor, a rare mineral that allows them to change their skin color and do other feats of magic. These island-dwelling people and their lands have been declared extinct by the Bassa Empire – until Lilong, a yellowskin warrior from the islands, shows up in Danso’s barn. Despite every warning he has been told about the islanders, Danso embarks on a quest to not only ensure her survival, but to rewrite the lies that he has been raised to believe in.

Islanders are not the only people persecuted for their appearance, though. According to the Bassa Ideal, a collection of contradictory rules that determine a person’s worth and destiny in the walled city, darker-skinned people belong to higher castes, lighter-skinned people to lower castes, and mixed people and immigrants are often left to straddle these arbitrary boundaries. Seeing that Son of the Storm isn’t post- or pre-colonial, it was refreshing to see that the entire novel contained African characters and systems of governance, as publishing overwhelmingly favors novels with systems based on Eurocentric and Western-centric standards of worth and beauty. While I am not the appropriate gatekeeper of West African literature, it seems more than suitable that Son of the Storm becomes a standard reading of African fantasy, and the fantasy genre as a whole.

Surprisingly, the most captivating part of this novel is not its tremendous worldbuilding (though that deserves heaps of praise) but its criticism of institutionalized “truth,” knowledge, and the meritocracy that upholds it. Esheme, an ambitious scholar who wants to transcend her marred caste status, embodies this. As a jali, she refuses to show any weakness, and calculates the majority of her decisions based on building her reputation and power. Her mother, Nem, is a popular fixer in the city who unfortunately weakens her caste status. Complicating her ascent to power is Danso, who she is joined (essentially betrothed) to. Wickedly smart and equally ambitious, Esheme often sees Danso and her mother as liabilities rather than important people in her life. Okungbowa carefully unravels her personality, and challenges her coldhearted beliefs through other equally-intelligent characters in the novel.

Hyperaware of the privileges that come with being a jali, Danso, Esheme, and Lilong are all aware that knowledge is gatekept in this world, and preserved by jalis who spread these dangerous myths to the castes below them. Class oppression keeps the empire moving, but the elites are careful to make sure that this is explained as a necessary force. Son of the Storm also addresses the state of migrant workers (some of whom become the most ardent believers in the Bassai Ideal) that move to the Empire’s capital for work so they can send money home. It was downright chilling to see how Esheme eventually leveraged these dangerous myths for her own climb to power.

Okungbowa leaves no stone unturned when it comes to building his world – religious practices and traditions appear as early iterations of prosperity gospel, monetized pilgrimages, bureaucratic institutions, and more. Unsustainable farming practices from the greedy Bassa Empire also lead to desertification and more immigrants seeking dehumanizing but financially profitable roles in the city. The world Okungbowa creates is riveting and filled with unpredictable political intrigue and cultural violence.

Okungbowa’s approach to death and violence is meticulously crafted. Many of the deaths are tragic and gruesome, but not for the brutal physicality of them. Rather, some deaths are tragic because of the ideals that caused their downfall. Okungbowa takes risks with plot, does not water down conversations to cool, emotionless negotiations. He also makes certain that characters have real stakes in these sharp, insightful discussions.

Other details throughout Danso and Lilong’s journey help make this world immersive – the religions, the migrants who keep the Bassa Empire running. The pidgin and slang, in particular, meant that the worldbuilding occasionally becomes dense. In some instances, I would have preferred some details to expand themselves in later installations of the Nameless Republic series. Then again, I am not sure that I would have the patience to wait for future installments. If generous details are Okungbowa’s only obvious shortcoming in this novel, then I would consider that a fantastic success. Some may find his use of “yellowskin” troubling, especially as it is a deliberately derogatory name, as are many of the slurs used for people of lower castes in the novel. Considering that Lilong is named after the Lilongwe river in Malawi, and any real-world cultural context would still be in reference to the African continent, the more important discussion seems to be around the consequences of violent speech, which Okungbowa explores in great detail.

Son of the Storm is ultimately the tale of an empire built on omitted truths, where scapegoats are common and brave witnesses are not. As the Bassa Empire tears itself apart to find Lilong and assert its stranglehold on history, its downfall might be the very people it sought to erase.

Maya C. James is a graduate of the Lannan Fellows Program at Georgetown University, and full-time student at Harvard Divinity School. Her work has appeared in Star*Line, Strange Horizons, FIYAH, Soar: For Harriet, and Georgetown University’s Berkley Center Blog, among others. She was recently long listed for the Stockholm Writers Festival First Pages Prize (2019), and featured on a feminist speculative poetry panel at the 2019 CD Wright Women Writer’s Conference. Her work focuses primarily on Afrofuturism, and imagining sustainable futures for at-risk communities. You can find more of her work here, and follow her on Twitter: @mayawritesgood.

This review and more like it in the June 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.