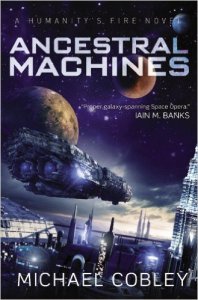

Paul Di Filippo reviews Michael Cobley

Ancestral Machines, by Michael Cobley (Orbit 978-0-316-22118-4, $15.99, 496pp, trade paperback) January 2016

When Bruce Sterling ended his fabled zine Cheap Truth in November of 1986 and urged his readers to take up the torch with their own zines, I responded by producing twelve issues of Astral Avenue, one per month steadily for the next year, before tiring of the expense and effort and ceasing publication. Text laboriously typed into a Commodore 128 computer and saved to floppy disks; outputted on a dot-matrix printer; pasted up with collages by hand; xeroxed at Kinko’s; stuffed into envelopes and mailed to about one hundred folks at the height of its circulation. Ah, such memories!

When Bruce Sterling ended his fabled zine Cheap Truth in November of 1986 and urged his readers to take up the torch with their own zines, I responded by producing twelve issues of Astral Avenue, one per month steadily for the next year, before tiring of the expense and effort and ceasing publication. Text laboriously typed into a Commodore 128 computer and saved to floppy disks; outputted on a dot-matrix printer; pasted up with collages by hand; xeroxed at Kinko’s; stuffed into envelopes and mailed to about one hundred folks at the height of its circulation. Ah, such memories!

One of my correspondents back then was a young lad from the UK named Michael Cobley. We had a nice correspondence for a time. Like me, Cobley had sold a couple of stories and wanted deeply to become a fully professional SF writer. Simpatico soul.

When Astral Avenue ceased independent publication (it did later morph into a column in New Pathways), Cobley and I fell out of communication, right down to the present moment, for no specific reason. Pre-internet, such interregna were common.

Here we both are, thirty years later, having realized, I think it is safe to say, the dreams of those ancient days, at least in part. And so, coming full circle to some extent, I get to renew my acquaintance with Michael Cobley through the medium of his new novel, Ancestral Machines. It feels good to reconnect.

The new book takes place in the universe of Cobley’s Humanity’s Fire trilogy, but is a standalone, we are assured. A good thing for me, who unfortunately has not read the trilogy.

In his prologue, Cobley wastes no time in flaunting his honed, merciless skills. He plunges the reader, without hand-holding or apologies, deep into a complexified far future whose essence is conveyed by strange actions embodied in a plethora of clever neologisms. This is red meat to me, and to many others, I hope. In short, Cobley is taking the techniques pioneered by van Vogt, Charles Harness and other bold visionaries and ramping them up for a purely twenty-first-century kind of SF that others such as Paul McAuley, Iain Banks and Ken MacLeod have hitherto essayed.

Thanks to Cobley’s talent, we quickly grasp the essential McGuffin. A strange, superscience polity more or less friendly with another power-nexus, the “Earthsphere,” is sending its representative, an AI embodied in a powerful drone shell and named Rensik, to liaise with a human soldier named Lt. Samantha Brock, so that both may travel together to investigate the arrival of a deadly intruder to the galaxy. That intruder is the Warcage, an ancient yet still potent megaconstruct of some two hundred separate planets entrained around a single sun. The Warcage travels through space and hyperspace as a unit, almost like a single ship, under the direction of the evil Shuskar. Their intentions must be investigated and stymied if necessary.

Meanwhile, two other threads are opened up, where action will flow separately, until all three sets of players converge in lively, logical, yet unpredictable fashion.

The outlaw ship Scarabus, captained by one Brannan Pyke, hosts a motley crew of loyal yet irascible aliens. They have recently been swindled by a fellow named Khorr, and now seek revenge. But it eventuates that Khorr is an agent of the Warcage, and more than a match for Pyke. Pyke and his crew will eventually end up on the worlds of the artificial system—a variety of exotic venues full of deadly action—and be subject to various adventures and exploits, some which they initiate, some which are thrust upon them.

Lastly we experience chapters where we get some insight into the life of First Blade Akreen—a loyal solider of the Shuskar who eventually turns his coat.

Cobley takes all these characters, plus others, and pushes them along a non-stop, unrelenting, madcap set of adventures. The brio and joy of this storytelling is contagious. Here is a space opera which unashamedly honors the roots of the genre while expanding the remit of the mode. To convey his incredible narrative thrust and whacked-out panache, I would have to say that the book is like Ringworld retold by Basil Wolverton, or perhaps some John W. Campbell-penned 1930s adventure rejiggered by Jodorowsky along the lines of The Incal.

A predominant feature of Cobley’s storytelling is an exuberant humor, a kind of high spirits that is exactly the opposite of so much of the ultra-serious gravitas seen in other space operas. Even when Captain Pyke (surely not a coincidence that his name echoes that of a famous captain from ST:TOS) is being morphed into a posthuman condition, his wisecracking bravado is undiminished.

One possible role model for Cobley that I would further adduce would be Poul Anderson in his Polesotechnic League saga. But whereas Anderson always reset his cast back to square one at the end of every adventure, as in most franchises, Cobley is not afraid to put his characters through major changes that leave them quite different at the end of the tale than they were at the start.

If you want a rousing space adventure full of sense of wonder that is also ideationally challenging, then you need look no further than Ancestral Machines.

I am proud to say I knew this guy way back when the world was young, and lived to see him accomplish so much.