Stefan Dziemianowicz reviews Year’s Best Weird Fiction

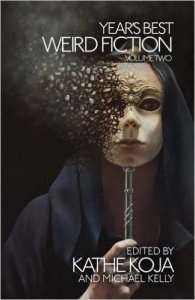

Year’s Best Weird Fiction, Kathe Koja & Michael Kelly, eds. (Undertow Publications 978-0-9938951-1-1, $18.99, 328pp, tp) October 2015. [Order from Undertow Publications .]

In her introduction to Year’s Best Weird Fiction: Volume Two, Kathe Koja, co-editor for this year’s edition, refers to the weird as that ‘‘sense of the strange’’ which derives from the understanding that there is more to our world than what our other five senses can convey. That’s a broad enough description to define the sensibility that runs through the nineteen eclectic stories she and Michael Kelly have reprinted in this volume. Although the authors of some of the stories selected also are represented in the other year’s-best compilations of stories from 2015, a number of the stories are neither dark nor horrific enough to have made the cut for the other titles.

In her introduction to Year’s Best Weird Fiction: Volume Two, Kathe Koja, co-editor for this year’s edition, refers to the weird as that ‘‘sense of the strange’’ which derives from the understanding that there is more to our world than what our other five senses can convey. That’s a broad enough description to define the sensibility that runs through the nineteen eclectic stories she and Michael Kelly have reprinted in this volume. Although the authors of some of the stories selected also are represented in the other year’s-best compilations of stories from 2015, a number of the stories are neither dark nor horrific enough to have made the cut for the other titles.

Several of Koja’s selections are steeped in the classic fairy and folktale tradition, or verge upon contemporary urban legends and cryptozoology. Siobhan Carroll’s ‘‘Wendigo Nights’’ begins ‘‘Lately I’ve been thinking about eating my children,’’ a line so startling in its implications that it virtually defies the reader not read any further. As its title suggests, the story is concerned with the cannibal spirit of Native American lore, one whose malignant influence is associated with a strange canister unearthed by a snowbound Arctic research team. The narrative is presented as a series of journal entries, ordered out of sequence so that they seesaw back and forth between days of normal operations and days of deathly cabin fever, the fulcrum being that moment when everything went suddenly, horribly wrong.

Carmen Maria Machado is represented by two stories, including ‘‘The Husband Stitch’’, a beautifully told story narrated by a woman who, as she grows from youth to maturity, points out the many campfire tales and urban legends that are based on ordinary life experience. For the duration of the story she conspicuously wears a pendant on a ribbon necklace, and anyone who is familiar with Washington Irving’s ‘‘The Adventure of the German Student’’ – itself based on a European folk legend – will know how the story is going to end. The counterpoint to Machado’s poignant tale is Nick Mamatas’s ‘‘Exit Through the Gift Shop’’, a wonderfully snarky account of how a Massachusetts town in need of tourist commerce milks a concocted urban legend perhaps a little too aggressively. Mythical creatures abound in Julio Cortazar’s ‘‘Headache’’ (translated into English for the first time by Michael Cisco), about a beaked mammal known as the mancuspia, and the altered sensibilities experienced by those who care for and feed them, and in Rich Larson’s ‘‘The Air We Breathe in Stormy, Stormy’’, about a deep-sea oil worker who falls in love with a semi-amphibious woman who lives beneath the rig. Isabel Yap, in ‘‘A Cup of Salt Tears’’, relates the amorous relationship that develops between a woman whose husband is dying of cancer and a kappa, or carnivorous water sprite of Japanese legend, who offers her a strange sort of succor. Sunny Morain’s ‘‘So Sharp the Blood Must Flow’’ is a sequel to Andersen’s ‘‘The Little Mermaid’’, written in the form of a revenge fantasy that will appeal to any reader who feels (as all readers surely do) that the title character of that story got a bum steer, given all of the sacrifices she made for love.

A variety of different voices and approaches distinguish Koja & Kelly’s other selections. In Karen Joy Fowler’s ‘‘Nanny Anne and the Christmas Story’’, a baby sitter looking after two young sisters increasingly – and unsettlingly – assumes the personality of their mother, who is being kept away from them by bad weather during the Christmas holidays. In K. M. Ferebee’s ‘‘The Earth and Everything Under’’, the relationship between a deceased husband and his widow causes disturbances to the natural order of their small town – possibly as a result of witchcraft, but possibly owing to their intense love for one another. Usman T. Malik’s ‘‘Resurrection Points’’ (also reprinted in Paula Guran’s year’s-best anthology) uses a young boy’s indoctrination into his personal powers for reviving the dead to explore differences between Muslim and Christian cultures. Kima Jones’s demon-haunted ‘‘Nine’ draws on the southern folklore tradition and Caitlín R. Kiernan’s ‘‘Bus Fare’’ is another of her tales of albino demon slayer Dancy Flammarion. Sarah Pinsker’s ‘‘A Stretch of Highway Two Lanes Wide’’ is a splice of fantasy and science fiction, about an amputee who receives a chip implant to power his prosthetic limb and the bizarrely altered sensorium he develops from technology intended for a completely different application. Not all of these stories would have been dark or horrific enough to have been chosen for the other year’s-best anthologies, and their inclusion among other stories that would ensures that they will be seen by a readership that might have overlooked them otherwise.

The most refreshing aspects of Year’s Best Weird Fiction: Volume Two are the same as for the other year’s-best compilations – the overwhelming majority of its contributors are writers who have come to editor and reader attention mostly within the past decade, and the quality of the work they are publishing in books and magazines that are predominantly niche markets is indisputable. Gone are the days when the horror publishing could muster only one year’s-best anthology, sometimes featuring stories that appeared in that book for the first time. If the stories in all four year’s best-anthologies from 2015 represent a culling from the vast trove of horror, dark fantasy, and weird fiction published in 2014, then the relative lack of overlap between their contents suggests that there is even more exceptional fiction from talented writers for the readers of these books to seek out.