Rich Horton reviews Short Fiction

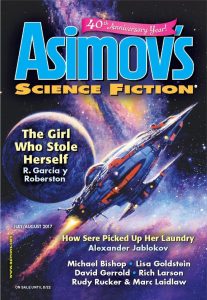

Asimov’s 7-8/17

F&SF 7-8/17

Uncanny 7-8/17

Clarkesworld 7/17

Fantastic Stories of the Imagination, People of Color Take Over Special Issue

Tor.com 7/17

There are two very entertaining novellas in the July-August Asimov’s, both by writers who have long been favorites of mine, and both of whom had long career hiatuses. Alexander Jablokov published nothing between 1998 and 2006; while R. Garcia y Robertson‘s story this month is the first I’ve seen from him since 2009. Good news! Garcia y Robertson’s “The Girl Who Stole Herself” is set in his usual future, with humans in numerous forms inhabiting space and other planets, and with slavery a major issue. Amanda is a pretty, 17-year-old girl being raised by a single mother, who is also a virtual Princess of Callisto, which makes her a prime target of slavers. The story spirals into a fast moving and, well, perky tale in which we meet Space Vikings and real Princesses and follow Amanda across the Solar System, and learn that her home is not what we first thought, and that her virtual existence is not quite as virtual as we thought. It’s breathless fun, if just a bit featherlight.

There are two very entertaining novellas in the July-August Asimov’s, both by writers who have long been favorites of mine, and both of whom had long career hiatuses. Alexander Jablokov published nothing between 1998 and 2006; while R. Garcia y Robertson‘s story this month is the first I’ve seen from him since 2009. Good news! Garcia y Robertson’s “The Girl Who Stole Herself” is set in his usual future, with humans in numerous forms inhabiting space and other planets, and with slavery a major issue. Amanda is a pretty, 17-year-old girl being raised by a single mother, who is also a virtual Princess of Callisto, which makes her a prime target of slavers. The story spirals into a fast moving and, well, perky tale in which we meet Space Vikings and real Princesses and follow Amanda across the Solar System, and learn that her home is not what we first thought, and that her virtual existence is not quite as virtual as we thought. It’s breathless fun, if just a bit featherlight.

Jablokov’s “How Sere Picked Up Her Laundry” begins what looks like a promising series. Sere Glagolit is a human living in Tempest, a crowded city on another planet, packed with “refugee intelligent species.” She has just lost her boyfriend and her job (courtesy of said ex-boyfriend) and she’s almost out of money, so she takes a risky and ambiguous free-lance assignment to track down information about a mysterious huge alien and, eventually, about some iffy urban renewal efforts. All this involves dangerous alien parasites, inscrutable alien customs, and of course some filthy alien laundry. Again, it’s lots of fun.

Rich Larson is back as well, showing off his stylish caper/adventure mode. “An Evening with Severyn Grimes” concerns Girasol, who has gotten involved with a radical group (sort of Occupy ramped up to full terrorist mode). She has agreed to help them kidnap Severyn Grimes, a very rich man who can afford to download his mind into young bodies. So far, so familiar, but the story goes in interesting directions, not taking any hackneyed sides, and also features some cool tech, as Girasol can download her own consciousness, dangerously, into intelligent systems. Girasol has her own motives, of course, if no very clear path to realizing them. The story is fast-paced, intelligent, and exciting.

The decidedly non-SFnal cover for the July-August F&SF illustrates David Erik Nelson‘s absorbing horror novella “There Was a Crooked Man, He Flipped a Crooked House“. (I guess we’re back to long story titles this month!) Glenn Washington is an African-American man in Detroit, trained as an architect but working for a real estate speculator while he tries to figure out what he really wants to do with his life. He works with Lenny, a big man who made me think of another fictional Lenny (from Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men) – an innocent, with some developmental issues. The two of them are investigating their boss’s latest purchase, a big house in remarkably good condition in one of Detroit’s worst neighborhoods. That means something strange is going on – in this case, very strange, as Glenn finds out when he goes in the front door and finds himself instantly in the back yard. There’s an obvious Heinlein reference there, as the house seems to occupy strange dimensions, but the vibe is really more Lovecraftian. Glenn investigates further, and things – involving an obscure architect, missing body parts, and some crooked police – get really scary.

I was also impressed by three stories from somewhat unfamiliar names, all of which take a rather jaundiced look at aristocratic pretensions. “The Masochist’s Assistant” in Auston Habershaw‘s story is Georges, the younger son of a modest family, who had taken a position as famulus to the Magus Hugarth Madswom. But Master Hugarth’s eccentricities seem only to further diminish Georges’s social standing. His main job seems to be to kill his Master, and then time how long it takes Hugarth to revive himself. Hugarth also tries to teach Georges the worthlessness of the high caste people whose approval he craves – but somehow the lessons don’t seem to take, leading to an amusing resolution at an event the Magus decides to crash.

Robin Furth‘s “The Bride in Sea-Green Velvet” is a nicely executed, if somewhat familiar, tale of the head of an ancient house who must sacrifice a bride to the sea every seven years. His brides are robbed from the grave, and re-animated, and now it is time for a special sacrifice, with an especially lovely bride. “I Am Not I” by G. V. Anderson is set in a distant future in which radically genetically modified humans – Varians – rule, with the few “normal” humans – Saps – barely surviving, and subject to “harvesting” for body parts. The narrator is a child of a highborn Varian who is a throwback to natural Sap genetics. She has been thrown out of her house, though she is able to pass as a Varian due to a few surgical modifications her mother bought for her. She takes a job for an ancient Acristologist, trying to earn money for better enhancements. The worldbuilding is the best aspect here, as well as the narrator’s morally compromised position – the story itself is nice enough, if perhaps just a bit routine, but I’ll keep my eye out for more in this milieu.

“The Worshipful Society of Glovers” by Mary Robinette Kowal (Uncanny, July-August) is an uncompromising story recalling Elizabethan London. Vaughn is an apprentice glover, caring for his seriously ill sister. Gloves in this world can be magically altered with the help of brownies, and such gloves can cast a glamor, or give strength – or cure people like Vaughn’s sister. Dealing with Faerie creatures is dangerous, and carefully regulated, but when Vaughn is all but ruined after he is robbed, and rather mistreated by his master, he is tempted to deal with a rogue brownie. Kowal doesn’t shy from the consequences of his decisions. It’s a moving and honest story.

I wonder if Rich Larson‘s “Travelers” from the July Clarkesworld was written in direct response to the film Passengers. In any case, it serves as a worthwhile corrective. The unnamed narrator is wakened early on a starship, 32 years from her destination. She finds one man also awakened, apparently a couple of months before she was, and learns that their equipment has malfunctioned, and they can’t go back to cold sleep. But something isn’t right… and soon she makes some horrific discoveries. Effective work – Larson is making an impression on me a bit like some other noticeably prolific writers (Robert Reed and Robert Silverberg, to name two) who show tremendous range and the facility to work interestingly with any number of speculative tropes. Speaking of Robert Reed, he has a fine piece in this issue, “The Significance of Significance“, a somewhat philosophical story about the effects of the discovery that the world is a simulation. These effects are played out mostly in the life of Sarah, who was an infant when the nature of the world was proven. The philosophical questions – and some further revelations about reality – are intriguing in themselves, and the characters are also well-handled. Indeed, we end up asking whether Sarah is the kind of person she is because of her lifelong awareness of her unreality, or whether that’s just an excuse of sorts.

The latest issue of Fantastic borrows an idea from Lightspeed‘s “Destroy” series, and is devoted to SF and Fantasy by people of color. Many of the stories are reprints, and quite worth your while, but my remit is originals. The best of these is Stephen Graham Jones‘s “Shadow Animals“, a slickly executed piece in which a young woman, flush with new love, stays home from work one day, does some housecleaning, and makes a discovery about her boyfriend. The closing twist is what we expect – but it is quite satisfying to see a hinge closed expertly. A bit more exotic is Minsoo Kang‘s “The Sacrifice of the Hanged Monkey“, about the disastrous attempt of an empire called the Sublime Rule to conquer a territory of worshippers of the Hanged Monkey (whose name is Bob). All goes as expected, but somehow the effect of this conquest on the theological disputes among Hanged Monkey worshippers leads to chaos. The account of the nature of the Hanged Monkey doctrines is clever, believable, and funny from one angle (his name is Bob!), but honest from another.

In Tor.com‘s July set of stories I thought “The Martian Obelisk” by Linda Nagata the best. It’s set in a future in which a series of disasters caused by human nature, environmental collapse, and technological missteps have led to a realization that humanity is doomed. One old architect, in a gesture of, perhaps, memorialization of the species, has taken over the remaining machines of an abortive Mars colony to create a huge obelisk that might end up the last surviving great human structure after we are gone. But her project is threatened when a vehicle from one of the other Martian colonies (all of which failed) approaches. Is the vehicle’s AI haywire? Has it been hijacked by someone else on Earth? The real answer is more inspiring – and if perhaps just a bit pat, the conclusion is profoundly moving.

Rich Horton works for a major aerospace company in St. Louis, MO. He has published over a dozen anthologies, including the yearly series The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy from Prime Books, and he is the Reprint Editor for Lightspeed Magazine. He contributes articles and reviews on SF and SF history to numerous publications.

This review and more like it in the September 2017 issue of Locus.