Paul Di Filippo Reviews Two Vancian Novels by Wm. Michael Mott

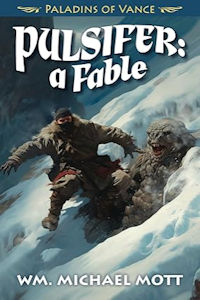

Pulsifer: a Fable, Wm. Michael Mott (Spatterlight Press 978-1619474918, trade paperback, 306pp, $16.95) Jan 2024

Pulsifer: a Fable, Wm. Michael Mott (Spatterlight Press 978-1619474918, trade paperback, 306pp, $16.95) Jan 2024

Land of Ice, a Velvet Knife, Wm. Michael Mott (Spatterlight Press 978-1619474932, trade paperback, 306pp, $16.95) Feb 2024

It is very seldom—perhaps almost never—that one opens up one’s copy of the Sunday New York Times and discovers that the lead article in the Magazine section is devoted to a still-living author whose roots in the pulpy Ur-soil of the science fiction and fantasy field are undeniable and deep. Oh, sure, you wouldn’t be too surprised to find Ursula K. Le Guin or J. G. Ballard or Ray Bradbury or Stanislaw Lem featured—four scribes who long ago burst forth from the genre ghetto. And if you spotted Philip K. Dick’s benzedrine beatific mug on the glossy page, you’d nod your head knowingly at his posthumous sanctification.

But to encounter a major worshipful and praiseful article on a guy whose most recent books had appeared from Tor and Subterranean, who had never been canonized by The New Yorker or Harold Bloom—well, that would be a deodand of a different hue.

Not to hide the name of this writer, who was the subject of “The Genre Artist,” by Carlo Rotella [shared link], NYT, July 15, 2009, I shall reveal all: the man was Jack Vance, finally getting his due just four years prior to his passing.

I hardly think that for this audience I need to catalog the wonders and virtues of Vance’s stories. Like Gene Wolfe famously first discovering The Dying Earth, most congenial readers are blown away by Vance and become lifelong fans. I know that’s how it worked with me.

And hopefully, thanks to the creative efforts of John Vance, Jack’s son, and his Spatterlight Press, new generations can continue to discover this wizard of prose. All of Vance’s work is available in sixty-two perpetually in-print books. What a treasure trove!

And yet, the avid fan must eventually reach the end of even such a copious catalogue. What then? Ah, Spatterlight has anticipated your every need and desire!

They have branched into new publications, authorized forays into the Master’s worlds, under the heading “Paladins of Vance.” The first such volume was Phaedra: Alastor 824, by Tais Teng. The second was a revival of Michael Shea’s earlier sanctioned outing, The Quest for Simbilis (1974). Third was Matthew Hughes’s Barbarians of the Beyond. (And of course Hughes’s own independently conceived Vancian tales are a big homage.) And now come numbers four and five, both by Wm. Michael Mott.

Before delving deeper into the texts, I will cut to the chase: these are the best books in the mode of Vance that I have yet encountered. Rich in invention and plot, beautifully written, inspired by Vance but not parodic or slavishly imitative, they will satisfy any fan of the Master. I hope there will be a dozen more installments.

First, though, what of Mott himself, not a familiar or widely documented name? His Goodreads page provides the most salient info, marking him as mainly an author of Fortean nonfiction. ISFDB believes that Pulsifer is his first novel. If so, this is a remarkable debut, confident, rich and handsomely constructed.

We are in the realm of the Dying Earth. But we find no familiar places or figures. Mott invents a whole new continent: Teumdoth, the land of the Final Winter. Unlike the more green and lush venues where Cugel the Clever wandered, all is ice and snow (for most of the year), with rugged mountains and hiemal forests of evergreens. There is a suggestion that this is an era well beyond Cugel’s time, reflecting the last days of the Dying Earth.

Centerstage is our roguish hero, Calim Pulsifer, the Velvet Knife. Pretty much completely amoral (although his code of ethics does feature certain complexities), Pulsifer has been exiled from his native land of Phontyque for his crimes against society. Stranded in a monster-haunted wilderness, with very few provisions or weapons, he is concerned with survival—and revenge. But first things first.

Seeking shelter, Pulsifer asks nicely at the lonely cabin of a hermit. Denied, he forces his way in and encounters a selfish Mage name Pog Trimmanax. (I think at this point you can start to admire Mott’s way with Vancian names.) Overcoming the fellow, Pulsifer takes what he needs, along with some spoils, and consigns Trimmananx to a nasty fate, before moving on.

Now, at this point, you feel that Trimmanax is done for and will never show up again. But Mott plays a great game of bringing characters back when you least expect them, in consequential and logical ways that alter the plot. It’s a great feature of these two books.

Now begins a succession of encounters as Pulsifer strives to return to civilization. And they are cleverly structured. We saw Pulsifer start out alone. Then he met Trimmanax, one other human. Next he encounters a primitive village. Then he joins a caravan, making an enemy of the strongest Mage in the world, Morskured Montath, with his deadly familiar, Firkui the hijret. He ends up in a small city, Skurpe. And ultimately he finds himself involved with rich Collectors and Mages in an immense mansion. All this from a freezing wilderness origin. At every stage, Pulsifer encounters a dozen menaces, both human and supernatural and monstrous, outwitting them all.

But then everything comes crashing down around his shoulders. His life seems over—until he encounters the literal creator of our universe, in metaphorical chains. He helps the deity escape, for which favor the deity promises to rejuvenate the Dying Earth. Additionally, Pulsifer makes a bargain for his own fortune, and now seems almost omnipotent. Is this the real end? Not quite! Just think of the tale by Grimm titled “The Fisherman and his Wife”.

I should avow here that Mott has mastered Vancian dialogue to perfection, full of wit, punctilio and subtext. I could quote scores of passages, but here’s one:

“Why do you worry over whether or not you possess a book which by your own doctrine, along with everything else in Reality, does not even exist? But I did not take the book, or anything else—nor will I submit to an undignified search! Allow me to rifle through the clothing while it hangs upon each of you, and probe the creases of your bodies—then such might be done to me in turn! But not before.”

“Pulsifer’s point is well-made,” Babu Racthu said. “We have no proof of his guilt. Pulsifer, can you support your claim of innocence?”

“We need to hear no lies!” Peredrin the archaeologist smote his fist in his palm. “I demand that you lock this rogue away, preferably in one of the impervious cages of Scoranmeher! You are the Master of the Caravan, and it is your duty to see that Equilibrium is maintained among the passengers!”

With Pulsifer thoroughly downcast at book’s end, one expects the sequel to follow a similar path—rags to riches—and it does, but in an utterly unpredictable and variegated fashion. Pulsifer’s very soul becomes a sought-after ingredient in a magical spell. He finds himself in vast underground caverns. Various temptresses beset him. (Mott wonderfully carries on the Vancian tradition of supernatural femmes fatales, such as the half-human, half-syleber witch named Sinfe.) Not only is Morskured Montath after Pulsifer’s hide, but so is every Mage of the Brotherhood. How can he possibly survive—even with djinn allies—and clear his name, so as to rejoin the urban society he so enjoys? Complications also from the first book continue to intrude. Pulsifer does triumph eventually, but it’s victory with a sting in its tale.

In these two books, Mott has shown us a unique voice that nonetheless proudly owes much to Jack Vance’s vision. This ingenious and highly entertaining exfoliation of Vance’s world does honor to both Mott and Vance. Long may the Paladins of Vance hold the field!

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.