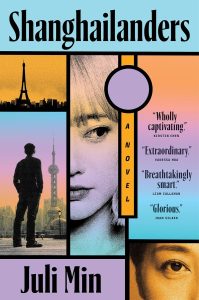

Niall Harrison Reviews Shanghailanders by Juli Min

Shanghailanders, Juli Min (Spiegel & Grau 978-1-95411-860-7, 270pp, $28.00, hc). May 2024. Cover by Charlotte Strick.

Shanghailanders, Juli Min (Spiegel & Grau 978-1-95411-860-7, 270pp, $28.00, hc). May 2024. Cover by Charlotte Strick.

In the first chapter of Juli Min’s Shanghailanders, another novel-in-stories, Leo Yang, a successful real estate developer, boards the maglev train from Pudong International Airport to downtown Shanghai. It is January 2040, and he is returning home after seeing off his wife, Eko, his eldest daughter, Yumi, and his middle daughter, Yoko, all heading to Boston. Yumi and Yoko are returning to different colleges; Eko is accompanying them, a decision Leo doesn’t think is necessary and which he slightly resents, since it leaves him to look after their youngest, Kiko, on his own. There has been an argument. Also on the train, the omniscient viewpoint reveals, are a stewardess, Shana, who has a slight connection to the Yangs (she realises, Leo doesn’t), and a young woman, Mary, travelling to Shanghai from rural China for the first time. All three remain lost in their own thoughts, which are almost entirely personal reflections, and do little to reveal this 2040 to us. Leo looks out at “water everywhere, like melted iron, snaking through the clusters of buildings”; Shana reflects on her prior job working on a much newer Beijing-Shanghai high-speed link, and the risk of radiation poisoning that went with it; Mary is excited to visit sights she has experienced only via her home screen, such as the “floating bubble” at the Tranquility Tower.

The use of perspective is deft, the prose silky and poised, and as a beginning the chapter is promising. But for me its most salient feature, so far as the rest of the novel goes, is its date. Shanghailanders is told in reverse: From the table of contents we already know that January 2040 is as far down the line as we will ever go, and that every subsequent chapter will work back towards our present, and ultimately into our past, terminating in 2014. We know, in other words, that what feel like beginnings are actually endings; that what follows will be about the path to this moment; that what we are looking for, in this chapter, is what might need to be explained. I am not someone who needs to see dramatic extrapolations to qualify a work as SF, but this version of January 2040 is so strikingly low-key, so little in need of explanation, that instead I found myself trying to explain the book, not as a matter of genre, but of project. Why set this story over this period, and tell it in this order? What is it, in other words, about this story that could not be transposed to 26 years of the recent past?

This question, which I’m sure will not bother all readers, needled at me while reading the next few chapters, which focus on different members of the Yang family. In January 2040, on an earlier trip, Eko helps Yoko deal with an unplanned pregnancy by hiding the abortion – which is not feasible in either Shanghai or Boston – within a trip to Paris to visit her mother. In September 2039, Kiko secretly signs up as an escort, and puts her virginity up for auction. In April 2038, Yumi and Yoko negotiate their awkward relationship while flat-hunting in Boston; in the background, Israel is at war. Like the opening chapter, these episodes examine deep emotions under glass. They have much to say that is worth hearing about femininity, family dynamics, and growing up into independence. And they feel as though, with only minor adjustments, they could be set now.

At this point I happened to reread the novel’s epigraphs, and started to form a theory about what Juli Min was up to. Both of the two epigraphs are taken from Eileen Chang’s Half a Lifelong Romance, a novel initially published in 1950, following serialization, before being re-edited and expanded 18 years later. Like Shanghailanders, it is a family drama set partly in Shanghai, albeit with a more conventional forwards-chronology; like Shanghailanders, it takes place over a precise period, in this case from 1931 to 1945; and crucially, like Shanghailanders, it makes almost no reference to surrounding historical events. Late in the novel, the Battle of Shanghai and the start of Japanese occupation are mentioned, but while Chang’s characters are not entirely insulated from its effects, little is shown and much has to be inferred; and in fact it is not the occupation alone that determines the final trajectory of the story, but the intersection of the occupation with a purely personal crisis.

Those who habitually calculate the ages of characters may have already worked out where this is heading: People attending college in the late 2030s will have been born in the early 2020s. True to Chang’s approach, the COVID-19 pandemic itself barely appears on-screen. The chapters skip from December 2026 to February 2020, and what little we do hear of the intervening period is from the perspective of the woman hired as the Yang’s live-in nanny. More importantly, this is not a novel about pandemic-induced psychological trauma; like their forbears in Chang’s novel, the Yang family are in a privileged enough position to surf through most of the social disruption, and in particular Yumi, Yoko and Kiko’s subsequent lives cannot be “explained” by the circumstances of their birth. But it is a novel in which the occurrence of the pandemic dramatically alters the range of decisions available to Leo and Eko, and as a result alters the trajectories of the whole family’s lives in ways we can only appreciate on reaching the pre-pandemic chapters.

That, I think, is why Shanghailanders covers the time period that it does in the way that it does. A novel whose furthest-forward time-point was 2019 would have a more ominous resonance, knowing what is about to happen; and a novel that took a forwards-linear approach to reaching 2040 might feel dramatically front-loaded. I think Juli Min is seeking a very specific effect, similar to that of Francis Spufford’s Light Perpetual (2021), in which the only divergence from our timeline is in the circumstances of specific individuals. It’s an effect which requires an absence of on-screen social upheaval or significant technological change after the mid-2020s, and that decision may seem implausible; it certainly looks very different to most of what we point to when we say “near future science fiction.” It is a future without novums. But to my mind, Min achieves what she seeks: Shanghailanders is graceful, poignant, and its story lingers after the last page is turned.

In Niall Harrison‘s spare time, he writes reviews and essays about sf. He is a former editor of Vector (2006-2010) and Strange Horizons (2010-2017), as well as a former Arthur C. Clarke Award judge and various other things.

This review and more like it in the June 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.