Alex Brown Reviews The Book Censor’s Library by Bothayna Al-Essa

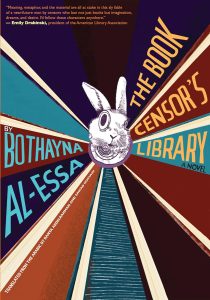

The Book Censor’s Library, Bothayna Al-Essa (Restless Books 978-1-63206-334-2, $18.00, 272pp, tp) April 2024. Cover by Joy Richu.

The Book Censor’s Library, Bothayna Al-Essa (Restless Books 978-1-63206-334-2, $18.00, 272pp, tp) April 2024. Cover by Joy Richu.

In a not-too-distant future in an unknown nation, we meet our unnamed protagonist in Bothayna Al-Essa’s new satire The Book Censor’s Library. All freedom of expression, individualization, and interpretation is banned. Everything revolves around God, government, and sex. Blasphemy is banned, but all holy texts have been heavily edited. No one may challenge the government, patriotism is mandatory, and any reference to the Old World (the era before the Revolution and the end of personal freedom) is prohibited. Sex is good, but only when it occurs between a married (cisallohet) man and woman for the purposes of procreation.

Our protagonist is a husband. His wife frets over their daughter, afflicted with a seemingly incurable case of imagination, a ‘‘vestigial tail’’ from the Old World. She fears photos of the president, talks to imaginary friends, and only wants to wear sparkly red shoes. Our protagonist is assigned to work at the Censorship Authority as a book censor. He must read a book, list out any and all violations, and decide whether it should be banned or not (as you can guess, most books are banned). Every year, the state holds a Purification ceremony where all the banned books from the previous year are burned in a massive celebration.

The novel is broken into five sections, each connected to a famous literary work: Zorba the Greek, Alice in Wonderland, 1984, Pinocchio, and Fahrenheit 451. These sections each reflect the protagonist’s journey from censor to reader. He discovers passion and freedom with Zorba, chaos and imagination with Alice, fascism and suppression with Winston, dreams and truth with a wooden puppet, and resistance and rebellion from Guy. Throughout it, he encounters absurd and surreal things, from an infestation of white rabbits to being overcome by purple prose. He meets a Cancer, a man who believes in saving books and reading them in spite of the law of the land. When his daughter is sent to a rehabilitation center (aka a house of torture and brainwashing) to ‘‘fix’’ her, things spiral even more out of control.

I don’t know which country, if any, Al-Essa, took as inspiration for this novel, but it’s depressingly apt for the current turmoil in the US. Book-banning has been on the rise since 2020, driven by waves of bigotry, Christian nationalism, fascism, and moral panics fueled by social media and misinformation. The American Library Association recently released its 2023 book banning statistics: there were attempts to ban 4,240 individual titles (47% of which were about queer and/or BIPOC stories) and 1,247 challenges.

As dire as these rates sound, the reality is even worse. These are only the challenges reported to ALA—for a variety of reasons, many schools do not report challenges to ALA—nor do these statistics include books preemptively removed, restricted, or not purchased, what is called soft or quiet censorship or self-censorship. Some school library workers are fearful of generating controversy or worried about potentially losing their jobs and so choose to do the censors’ work for them. I, of course, being a ‘‘poke the bear in the zoo’’ kind of school librarian, have increased my purchase of diverse materials. I know how important it is to see a variety of experiences and identities. A book got me thinking about my gender (Blanca & Roja by Anna-Marie McLemore) and a book that opened my eyes to asexuality and aromanticism (The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality by Julie Sondra Decker). Books taught me I could step outside the tiny, uncomfortable box society put me in as a kid. It’s no wonder in The Book Censor’s Library the book banners target queer stories, and it’s no wonder the book banners in the real world are doing the same. If you take away a person’s options, if you make them think the only thing they’re allowed to be is this narrow thing or that narrow thing, then they won’t realize there are whole universes out there of ways to experience your body.

Al-Essa’s satirical novel is fierce and unrelenting. There is humor, but it’s of the gallows variety. The plot centers on books, but it’s about so much more than just that. It’s about critical thinking, creativity as an act of rebellion, the difference between resistance and revolution, and the lengths we’ll go to protect the people we love. The novel twists the knife, but bails out before the final cut. And with so many moments borrowed from other stories, the original stuff tends to get lost. That said, The Book Censor’s Library has a lot of vital and timely things to say that make any stumbles worth overlooking.

Alex Brown is a librarian, author, historian, and Hugo-nominated and Ignyte award-winning critic who writes about speculative fiction, young adult fiction, librarianship, and Black history.

This review and more like it in the May 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.