Paul Di Filippo Reviews HIM by Geoff Ryman

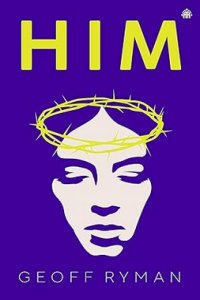

HIM, Geoff Ryman (Angry Robot 978-1915202673, trade paperback, 366pp, $18.99) December 2023

HIM, Geoff Ryman (Angry Robot 978-1915202673, trade paperback, 366pp, $18.99) December 2023

The subgenre of SF that deals with religion is a copious, healthy, and growing one, albeit not as large as some branches of fantastika. From del Rey’s “For I Am a Jealous People!” to Blish’s A Case of Conscience; from Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land to Russell’s The Sparrow; from Bishop’s “The Gospel According to Gamaliel Crucis” to my own tale, “Personal Jesus”, writers have examined the deep human hardwired urge towards spirituality with many alternative, speculative and counterfactual tropes. (And of course, fantasy and horror generally posit the reality of gods and the supernatural as a given, making it integral to their plots.). But the selection of stories that deal with canonical Christianity is much smaller that the larger, inclusive set. And the sub-subset of stories about Jesus and His Associates is tiny at best.

We have, of course, Moorcock’s Behold the Man and Malzberg’s The Cross of Fire. Paul Park did yeoman work with The Gospel of Corax and Three Marys. In a humorous vein, we of course always have Life of Brian, and Moore’s Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal. But once you get past these obvious titles, the roster is almost exhausted. It’s devilishly hard (pun intended) to say something new about a historical figure who is arguably the most-written-about personality in history.

But such a challenge is well within the bailiwick of Geoff Ryman, one of the field’s most ambitious and accomplished and daring writers. His new novel manages to recast the familiar Life of Christ in ways that are both estranging yet authentic.

And those two adjectives—“estranging yet authentic”—form, I think, the core conceits of what most of these genre authors are attempting. They want to strip away the millennia of familiar associations that have been layered onto Christ and his church—the often-schmaltzy patina that gives us something like the famous “Head of Christ” by artist Warren Sallman—and substitute Dali’s “Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubicus).” By peeling away the layers of history and cant, they will show what the primal forces are. A “Secret Origin” story if you will.

And often the historical and imaginary figures in this interzone era starting with the birth of Christ and extending up to his death and resurrection are necessarily portrayed as aliens, much in the SF manner. Their distant Judeo-pagan origins, morphing to nascent Christian beliefs, partake of the famous thesis promulgated by Julian Jaynes in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Our religious ancestors are seen as having direct conduits to the mystical that we lack today, with strange motivations, reactions and desires.

This is definitely the effect that Ryman’s HIM achieves. His characters manifestly do not share our twenty-first-century weltanschauung. The past is another planet—they do things in an alien manner there.

We open with a young woman named Maryam, obviously the soon-to-be Mother of God. This novel will remain centrally her story, although of course Christ will dominate the stage for vast portions of the tale. And in fact, Maryam is alone at the end of the book, completing her biographical circle.

Maryam reveals to her mother that she is pregnant by no human man. Naturally, this is scandalous, whether true or not. Luckily for the preservation of the family’s civic status, Maryam can be married off to Yosef, a local eccentric, visionary and ne’er-do-well, “in danger of being stoned.” Yosef reluctantly agrees to a strangely sexless alliance, and the pair are sent in exile to Nazareth.

I should note here that Ryman’s evocation of the Middle Eastern landscape and culture is like a smack upside the head. The heat, the grit, the poverty; the quotidian artifacts and tools, the clothing—everything assumes a tangibility that helps to ground the novel in its otherness.

So by Chapter 3 the couple are settled into their new community, meeting people, scrounging a living. Then Mary gives birth. And here comes Ryman’s Big Reveal, which has to be shared here in order for the rest of the book to be discussed: Maryam gives birth to a girl child whom she names Avigayil. Where’s Baby Jesus? Right here in a female body.

Maryam began to feel in the weight of that calm stare something she could only call God. God, Maryam was certain, looked out through those infant eyes. The child didn’t cry ever. She signalled for food by smacking her lips. She indicated with a sniff that she needed to wee…

What follows for fully half the book is the strange growing up and maturation of Avigayil. The story takes on an almost soap-opera quality, revolving around all the interpersonal interactions amongst various neighbors, in-laws, siblings (Yosef manages to impregnate Maryam six more times by a kind of manual procedure) and officials. Larger scale events intrude from time to time. But basically, it’s like some fascinating “Early AD Reality Show,” with Avigayil as the dominant personality.

The first big quantum leap comes when Avigayil declares herself a boy and takes the name Yehushua. She becomes a he, their backstory known to some, but not to others, the newcomers, who are attracted by Yehushua’s strange magnetism, bravery and preaching. Trouble comes and goes. The overarching poverty of the family’s existence is unabated. Maryam is not pleased to have lost a daughter and gained a problematical son. We watch all this happen with a vivifying granularity.

Then, literally midway in the book, when Yehusua is about thirty years old, Yosef dies, and this triggers the Son of God to hit the road, taking only his brother Yakob along. Left at home, Maryam is adrift, until sister Babatha informs her of her Son’s doings.

“She’s preaching.” Babatha blurted out a laugh, shook her head, put a finger under her nose. “She’s walking around. In public. Teaching scripture. Worse than that, I hear she’s gone beyond any of the Perisayya. For changing scripture. Mmm-hmm. Saying that her talking has more authority than the Law or the Temple. And you know how clever she can be, twisting everything around. She’s got people following her.”

From this point to the book’s inevitable end, Yehushua’s career follows more or less the path we all know today, but with revisions, quirks, individualizing moments only Ryman could imagine. Various miracles, confrontations, triumphs, and defeats accrue. Maryam eventually joins the Son and becomes His amanuensis. But despite all of her advice and help, the redemptive tragedy ends as it must, in the Crucifixion—a depiction of which Ryman avoids, as he follows a fleeing Maryam down a lonely road, where she and we meet—

Ah, what exactly do we meet? This is where Ryman pulls a Holy Ghost out of his hat, a literal deus ex machina which reminded me strongly of nothing so much as one of Harlan Ellison’s most famous stories. In retrospect, clues to this denouement abound. In fact, the descriptions of Yehushua’s miracles can be seen retroactively as the depiction of a certain kind of counterfactual branching node. Here is the healing of a leper:

“All right, yes. Be clean.” The words were muttered, bitten off, almost covert.

The whole universe blinked.

The stars seemed to go out for a moment, and all the air seemed to be pulled out of their lungs like a tide. The world itself was dizzy. It swayed as if drunk. The honking geese overhead flew backwards. Behind them, there were cries and queries from the multitude.

Then the world shook itself awake.

The man was whole. The skin on his face plastered down and smooth; his bare legs no longer swollen but firm and shapely with muscle. Both feet and all his fingers and toes were in place. He was young, not yet twenty. Maryam had thought him ancient.

“The air. I can feel the air,” he said in a young, soft voice full of wonder.

Partaking of the same amazement-fraught anachronistic strangeness as Gene Wolfe’s Soldier of the Mist and its sequels, Ryman’s transgressive, down-and-dirty hagiography recalibrates everything we thought we knew about Jesus, to show us The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Lovers Even.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.

There are still books about Jesus and his apostles that are waiting to be read. Adam McOmber’s JESUS & JOHN (which Locus never reviewed) is a recent surreal novella about the relationship between the two. It’s a gnostic beaut!