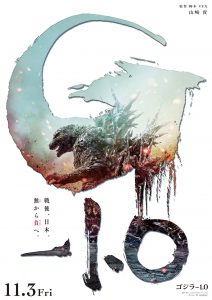

Exit, Pursued by a Kaiju: Josh Pearce and Arley Sorg Discuss Godzilla Minus One

Arley: I agree. This movie was GREAT. They started with unusual characters. You don’t see a lot of movies where the star is a disgraced suicide pilot, for example. Grounding the story with in interesting, relatable characters makes it so that you can actually capitalize on the horror aspects of Godzilla. Viewers can get engaged with the horror that is Godzilla, rather than just being like, “Oh, all I’m looking at is special effects.”

Josh: There are immediately personal stakes instead of just landmarks being destroyed.

Kamikaze pilot Koichi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) manages to survive the last desperate actions of World War II as well as an early Godzilla attack. It’s a fortunate outcome, considering the odds, but others are quick to point out that his survival is due only to his cowardice — a perspective he agrees with, and one which is eating him up inside. His airplane mechanic Tachibana (Munetaka Aoki) blames Shikishima for not single-handedly stopping Godzilla from destroying their outpost and killing the rest of the garrison. Likewise — after Shikishima returns to find Tokyo burned to the ground, his home destroyed, and his parents killed — his neighbor Sumiko (Sakura Ando) berates him for not sacrificing his life to stop the American military, seeing “people like him” as the reason they lost the war.

As Japan slowly recovers, Shikishima takes in a young woman, Noriko Oishi (Minami Hamabe), who has adopted an orphaned baby named Akiko (Sae Nagatani). Over the next few years, they form a sort of family unit, rebuild their house, and find what jobs they can. Life goes on. But then the Americans start nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll.

As Japan slowly recovers, Shikishima takes in a young woman, Noriko Oishi (Minami Hamabe), who has adopted an orphaned baby named Akiko (Sae Nagatani). Over the next few years, they form a sort of family unit, rebuild their house, and find what jobs they can. Life goes on. But then the Americans start nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll.

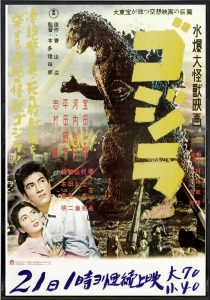

Arley: The original Godzilla is talking about nuclear weaponry, and this one is talking about war itself and the way Japan (and perhaps other nations) saw people as expendable. They infused the film with all these really nuanced questions. The bombing of Tokyo was central here and many people, historically, saw that bombing as a humanitarian crisis and a war crime. There are Japanese people who sued the Japanese government, they blamed the government for not giving up the war earlier. I feel like, as much as I got out of this movie — and I loved this one, I thought it was saying so many cool things — I still feel like there are probably levels of subtext and nuance and maybe even more overt theme that even I wasn’t getting, that you maybe have to be more involved in the sociohistorical contexts to fully understand. There are probably conversations that are more common or explored in Japan via Japanese literature and film than what I’m personally exposed to. But even without fully grasping all that, this movie is so good.

Josh: The dialogue is also about survivor’s guilt. He survived this war, but all these people did not. He was supposed to protect the country, or at least delay the attacks so some people would live perhaps a little longer, who knows? So it’s a lot of that, and the shame of being a veteran of a defeated army, in a nation that’s been completely destroyed by another country. How do you bring honor back to yourself or to your military when your commanding officers and your politicians have betrayed you? There’s a lot of stuff going on. You basically don’t even have to have Godzilla in there, it could’ve been a movie just about post-war Japan.

Like Shin Godzilla, this film was made by Toho, the company responsible for the original Godzilla movies. And again, it’s the same basic story: an atomic bomb wakes up Godzilla, he fucks things up, scientists have to stop him. But this film features excellent reinterpretations of that story — Shin Godzilla was about the collective protagonist and the struggles of bureaucracy, while Godzilla Minus One is much more personal, with character arcs and complicated love stories. Evidence that it is possible to get creative using the same source material.

Like Shin Godzilla, this film was made by Toho, the company responsible for the original Godzilla movies. And again, it’s the same basic story: an atomic bomb wakes up Godzilla, he fucks things up, scientists have to stop him. But this film features excellent reinterpretations of that story — Shin Godzilla was about the collective protagonist and the struggles of bureaucracy, while Godzilla Minus One is much more personal, with character arcs and complicated love stories. Evidence that it is possible to get creative using the same source material.

The creativity in Godzilla Minus One extends to the visual design, with an intentionally retro look. Monsters look like stop-motion, sets look like miniatures, vehicles look like models, and backgrounds look like rear-screen projection (although nearly all of this is actually CGI). When swimming in the ocean, Godzilla has a predatory, cat-like menace. On land, he has the cumbersome walk of a man in a bulky rubber suit, but also the ponderous inevitability of a force of nature.

Arley: I was even looking at Godzilla’s neckline! I felt like maybe I could find the cutout for the eyes of the person in the suit!

Josh: I love the fact that the tanks came out shooting and they look like toys. The fact that they can make it so kind of cheesy, side-by-side with these gigantic nuclear blast effects — that enhances the feeling of horror that you’re just a plaything to this giant monster.

Arley: There’s a lot of value in seeing this on a big screen. You won’t have the same visceral impact on smaller screens I think, and a lot of this gives you great visceral reactions. Except I didn’t like the way his dorsal plates pop out. I was like, what in nature does anything along those lines?

Josh: But what animal in nature breeds atomic fire? We’re talking about Godzilla, here.

Arley: I’m fine with that. I can buy into him blowing up a whole naval fleet! I guess we all have some line that we don’t want crossed. I reacted to the popping plates the way you reacted to Namor’s itty bitty wings in Wakanda Forever!

Arley: I’m fine with that. I can buy into him blowing up a whole naval fleet! I guess we all have some line that we don’t want crossed. I reacted to the popping plates the way you reacted to Namor’s itty bitty wings in Wakanda Forever!

Josh: I was completely sold on this movie after the first boat scene, when they do the whole Jaws sequence. It was so fun! You’re in this dinky little boat, how are you gonna fight Godzilla? They establish all the rules and escalate the situation perfectly. I would watch this movie again just for that whole sequence, it was so good.

Arley: This film had more heart and tension than most Godzilla movies, and it’s because you connect to the people first. Godzilla comes and the first thing he does is kill a bunch of people, it’s not like random cities are being toppled over, or like, the way American movies might kill a bunch of people and project this idea that “it’s fine because the protagonists are okay.” Here, death is relevant, it’s important, even if it’s a character we barely saw. They make the danger of Godzilla palpable in this movie.

Josh: Because the main character was a suicide bomber, his whole arc seemed to be leading up to redeeming himself through sacrifice. I thought, “This guy’s gonna die.” So you’re watching with the expectation that even the main character is not safe. Nobody’s safe. I thought he was gonna attack Godzilla with his airplane in the very first action sequence, so I had this expectation, and it eventually paid off, but they took the entire movie to get to it. They had me on the hook for the entire time. Very good setup, very slow burn, and then a satisfying payoff at the end.

Arley: Yeah, even having this cool airplane is not just a throwaway, sparkly moment. They use this to critique the Japanese position in war, and even that is educational.

Josh: Yeah, I saw the seat and it had German lettering on it and I said, “Oh, they put a different seat in there.”

Arley: But it also hinges on him making a decision: Am I going to kill myself after all, or am I going to live? For me, this film is not really about redemption, so much as it is about acknowledging the past and moving on. Saying, basically, all this stuff was horrible, but we are still here, we are alive, and we have to move into the future, we have to embrace the future and decide what to do with ourselves. This is especially expressed in the younger character who later they tell to stay behind, who never went to war, who perhaps embodies hope for the future. Japan is known to have done some terrible things during the war – they sided with the Nazis and Italy and many Japanese soldiers committed abhorrent acts. I’m not sure if this is accurate but I can see Godzilla as a metaphor for Japan reckoning with its past, Godzilla as the looming guilt, a devastating monster that the survivors have to face.

As each defense and countermeasure fails to slow Godzilla’s rampage, the characters get increasingly desperate. The audience can watch them put all the puzzle pieces together, based on what has wounded him in previous attacks. Giving the heroes or the humans hope that they can do something, if only they can figure it out in time, is a great way to ratchet up the tension and up the stakes. If instead they decided they were 100% doomed, then the only workable resolution would be a deus ex machina. An anti-climax. Fortunately, Godzilla Minus One doesn’t insult its audience, and allows us to figure things out along with the characters.

As each defense and countermeasure fails to slow Godzilla’s rampage, the characters get increasingly desperate. The audience can watch them put all the puzzle pieces together, based on what has wounded him in previous attacks. Giving the heroes or the humans hope that they can do something, if only they can figure it out in time, is a great way to ratchet up the tension and up the stakes. If instead they decided they were 100% doomed, then the only workable resolution would be a deus ex machina. An anti-climax. Fortunately, Godzilla Minus One doesn’t insult its audience, and allows us to figure things out along with the characters.

Even Shikishima and Noriko’s relationship takes unexpected turns. The assumption, obviously, is that they’ll fall in love, but it’s really not that simple. They both declare themselves unworthy of the other person because of their pasts, and this interplay leaves us invested in her character and in her safety. If you’re paying attention, you know the danger that Noriko is in, even before the movie says, “By the way, Godzilla is heading toward where she works.” The love story is elevated from merely Will he save her? to Will they even survive? Or, conceivably, Will the world survive?

Arley: Godzilla Minus One isn’t like the American versions of Godzilla (such as Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla, or Godzilla: King of the Monsters, or Godzilla vs. Kong). Those have very standard American characters in a standard American narrative, with very American values: “I’m a dude, I have to save my family” kind of stuff. It’s so basic. This movie is about Japanese people wrestling with or contending with the things they’ve done as a nation during World War Two, and the way that what they’ve done is also self-destructive. Topics that are more important than just oh, look, my wife needs me to rescue her. My daughter needs me to rescue her. Let me act macho and take things over. Our narratives too often make it all about showcasing what an American man can do. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I loved Die Hard and most of the Fast and Furious movies and things like that. But I think you have to be aware of what these kinds of things are saying, how they both represent and impact our culture. And when the best you can do is bring that same sensibility to a Godzilla movie, it just feels trite. The TV show, Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, is actually pretty good. But again, this is because it centers more interesting characters (played by Anna Sawai, Ren Watanabe, Mari Yamamoto, and Kiersey Clemons), and unusual situations, which makes the story more compelling. Except for, you know, Kurt Russell and his son both doing a fairly standard Kurt Russell.

Josh: When the younger guy in Godzilla Minus One tries to join the veterans and he’s like, “I want to fight,” their immediate reaction is, “You’re lucky you’ve never seen war.” There’s no glory in it, you were the fortunate one who never had to go to war. They’re telling him to embrace and accept that the older generation already did it so that he wouldn’t have to.

Arley: Yeah, which is another difference from the glamorization of American cinema, which has more movies that are like, “War is awesome, killing people is great. This is what being an American hero looks like, blowing shit up.”

Arley: Yeah, which is another difference from the glamorization of American cinema, which has more movies that are like, “War is awesome, killing people is great. This is what being an American hero looks like, blowing shit up.”

Josh: Godzilla Minus One is arguing against the message that the only way you can find personal glory is to go out and kill someone else, or the assumption that you haven’t served your country unless you’ve been in the military, that whole idea that Starship Troopers is satirizing: service guarantees citizenship. There are many other ways to serve a country or to be part of its society. I think Americans should not be allowed to do Godzilla content anymore.

Arley: Not until they get their shit together.

Josh: Will they really ever get their shit together?

Arley: No, probably not.

Written and directed by: Takashi Yamazaki

Starring: Minami Hamabe, Ryunosuke Kamiki, Sakura Ando, Kuranosuke Sasaki, Hidetaka Yoshioka, Munetaka Aoki, Rikako Miura, Yûki Yamada, Michael Arias, Sae Nagatani, Orio Nakamura, Yûya Endô & Kisuke Iida

ARLEY SORG, Senior Editor, has been part of the Locus crew since 2014. Arley is an associate agent at kt literary. He is a 2022 Kate Wilhelm Solstice Award recipient and a 2023 Space Cowboy Award recipient. He is also a 2021 and 2022 World Fantasy Award finalist and a 2022 and 2023 Locus Award finalist for his work as co-Editor-in-Chief at Fantasy Magazine. Arley is a 2022 Ignyte Award finalist in two categories: for his work as a critic, and for his essay “What You Might Have Missed” in Uncanny Magazine. He is Associate Editor and reviewer at Lightspeed & Nightmare magazines, columnist for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and interviewer at Clarkesworld Magazine. He grew up in England, Hawaii, and Colorado, and lives in the SF Bay Area. A 2014 Odyssey Writing Workshop graduate, Arley has spoken at a range of events and taught for a number of programs, including guest critiquing for Odyssey and being the week five instructor for the six-week Clarion West workshop. He can be found at arleysorg.com – where he ran his own “casual interview” series with authors and editors – as well as Twitter (@arleysorg), Blue Sky, and Facebook.

JOSH PEARCE has had more than 100 stories and poems published in top science fiction magazines, including Analog, Asimov’s, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Bourbon Penn, Cast of Wonders, Clarkesworld, Diabolical Plots, Interzone, Nature, On Spec, Weird Horror, and elsewhere. Find more of his writing at fictionaljosh.com. One time, Ken Jennings signed his chest.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.