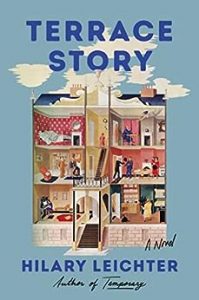

Ian Mond Reviews Terrace Story by Hilary Leichter

Terrace Story, Hilary Leichter (Ecco 978-0-06326-581-3, $28.00, 288pp, hc) August 2023.

Terrace Story, Hilary Leichter (Ecco 978-0-06326-581-3, $28.00, 288pp, hc) August 2023.

Hilary Leichter’s Temporary was one of the few joys I experienced during the COVID lockdowns of 2020. The novel took a satirical jab at the ephemeral nature of the gig economy, with Leichter’s protagonist temping in roles as varied as a mural artist, a pirate (of the parrot and eye-patch variety), and a CEO of a multinational corporation. This never-ending search for permanence resonated at a time when a person’s job security relied on whether they could work from home. That lack of certainty is amplified in Leichter’s much-anticipated follow-up novel Terrace Story, which shifts attention from the job market to our postpandemic anxieties of protecting the ones we love on an ecologically fragile planet.

Terrace Story isn’t a single narrative but four interconnected tales, each with a title inspired by an architectural design. The first of these, ‘‘Terrace’’, originally appeared in Harper’s Magazine, where it was part of a portfolio of work by Leichter that won the 2021 National Magazine Award for Fiction. Rising rent prices see Edward, Annie, and their baby, Rose, downgrade into a tiny apartment in the city. Where they’d previously had the view of a lovely ginkgo tree, the ‘‘introverted windows’’ of their new lodgings are ‘‘gated and clasped and huddled around a central shaft.’’ Consider their surprise when Annie’s coworker, Stephanie, comes over for dinner, suggests they eat outside and opens the nappy closet to reveal, Narnia-style, a terrace ‘‘decorated with strings of twinkling lights. Knotted vines gathered around the edges, forking and blooming and racing up the sides of the apartment.’’ When Annie and Eddie realise that the terrace – with its ‘‘table and four chairs, a grill, and the kind of sturdy umbrella one could shove open on a sunny afternoon’’ – appears only in the presence of their friend, they make any excuse, no matter how flimsy, to invite Stephanie over to the apartment. ‘‘Terrace’’ is a sublime piece of writing. The initial absurdist gloss, a family and friend enjoying the frothy delight of an impossible sun-drenched terrace, shifts gradually darker as Stephanie inveigles her way into Annie’s marriage, her job, and her life.

Initially, it’s unclear how the next story, ‘‘Folly’’, is linked to ‘‘Terrace’’. We join George and Lydia arriving at a funeral on a ‘‘crumbling’’ estate, unsure why they’ve attended or who has died. At one point, they leave the mansion and head out into the gardens, where they discover a folly, ‘‘a stone wreckage, like a medieval tower that had sunk below the surface of the earth.’’ We come to learn that George is an English Professor; that Lydia is a journalist who specialises in extinctions; that a once lively marriage has become a series of ‘‘blind alleys and impasses’’; and that they have a daughter named Anne (yes, these are Annie’s parents). George and Lydia split apart. They love other people. They eventually come back together, their story arriving full circle as they return to the crumbling estate and the folly. Again, the shift in register, the dream-like atmosphere of the opening transitioning into something more domestic and every day, makes this story about love, infidelity and architectural (and temporal) anomalies such a beguiling read.

Told from Stephanie’s perspective, ‘‘Fortress’’ is easily the longest piece in the book and the lynchpin that ties Terrace Story together. The latter becomes apparent on the opening page, revealing a trait about our protagonist that makes us view ‘‘Terrace’’ in a completely different light (I’m avoiding spoilers). What transpires is a portrait of a lonely woman (Stephanie as the titular ‘‘Fortress’’) shunned by her family and friends, who finds solace in a married couple, Annie and Eddie, and their daughter. That daughter, Rose, now all grown up, is the subject of the book’s final tale, ‘‘Cantilever’’. My refusal to spoil the pleasures of this novel holds me back from describing where ‘‘Cantilever’’ takes place. But like the stories before it, ‘‘Cantilever’’ is about the fear of losing those we love in an inherently unstable environment.

Terrace Story has the poignancy and profundity that you find in the work of Jennifer Egan and Emily St. John Mandel, but with an eye for the absurd and quirky that you rarely see these days. An impossible terrace, an extinction event every week, a creepy, broken-down estate trapped in a moment in time – surreal ideas that Leichter coherently stitches together, affording them a significance that is impossible to disregard or laugh off. Added to this is Leichter’s clever and subtle manipulation of space – whether it be the tiny apartment or Annie noticing something wrong with her desk at work – and how this plays not only into the novel’s genre elements where the very nature of reality comes into question but how families and friendships are moulded, fractured and bound by the scaffolding around them. And to top it all off, the writing is beautiful, with word choices and phrases (I keep coming back to ‘‘introverted’’ windows) freighted with a quiet emotion. The more I think about it, the more I’m willing to go out on a literary limb and proclaim Terrace Story as my favourite book of the year (so far).

Ian Mond loves to talk about books. For eight years he co-hosted a book podcast, The Writer and the Critic, with Kirstyn McDermott. Recently he has revived his blog, The Hysterical Hamster, and is again posting mostly vulgar reviews on an eclectic range of literary and genre novels. You can also follow Ian on Twitter (@Mondyboy) or contact him at mondyboy74@gmail.com.

This review and more like it in the August 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.