Anna-Marie & Elliott McLemore: No Borders

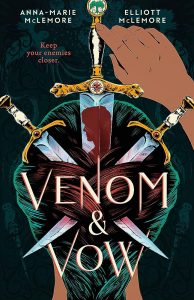

ANNA-MARIE MCLEMORE & ELLIOTT MCLEMORE are married co-authors of Venom & Vow (2023).

Anna-Marie is a queer, Latine, nonbinary author who grew up in Southern California. Their debut YA The Weight of Feathers appeared in 2015, and other books include Otherwise Award winner When the Moon Was Ours (2016), Wild Beauty (2017), Blanca & Roja (2018), Dark and Deepest Red (2020), Miss Meteor (2020, with Tehlor Kay Mejia), The Mirror Season (2021), current Ignyte Award finalist Lakelore (2022), and Self-Made Boys: A Great Gatsby Remix (2022). Flawless Girls and The Influencers are forthcoming in 2024.

Excerpt from the interview:

Elliott McLemore is a “nonbinary trans guy” originally from Colorado. Before beginning to write fiction, he was focused on professional research and writing, along with advocacy, including working toward adding nonbinary gender identifiers to legal documents in California. Venom & Vow (2023) is his debut.

Elliott McLemore: “I have written in many different forms over time. When I was young, I was one of the kids who had this idea for this story, and it must happen now! I would do little illustrations and put it all together the best I could and tie it up with yarn and coerce an adult into writing down what I wanted because I didn’t know how yet. I was one of those kids. Obviously, I got really into any and all writing that had to happen throughout schooling. I eventually stopped doing as much creative writing, because I was doing so much writing academically or professionally that I just lost any creative writing impulse. It was like all the words were out of me by the time I was done. Eventually, Anna-Marie and I got to do something together, and I got to actually creatively write again! It was glorious!”

Elliott McLemore: “I have written in many different forms over time. When I was young, I was one of the kids who had this idea for this story, and it must happen now! I would do little illustrations and put it all together the best I could and tie it up with yarn and coerce an adult into writing down what I wanted because I didn’t know how yet. I was one of those kids. Obviously, I got really into any and all writing that had to happen throughout schooling. I eventually stopped doing as much creative writing, because I was doing so much writing academically or professionally that I just lost any creative writing impulse. It was like all the words were out of me by the time I was done. Eventually, Anna-Marie and I got to do something together, and I got to actually creatively write again! It was glorious!”

Anna-Marie McLemore: “I’ve always loved stories – I grew up in a family that loved stories, loved books, and was a very reading-aloud kind of family. That is so important to me, because I don’t think I would have learned how to read if parents, siblings, family members, community members, teachers, librarians, if they hadn’t read to me. That’s so much of how you learn to read – with dyslexia, especially.

“When I was a little kid I thought, ‘Maybe I can be a writer; maybe I can write one of these things, one day.’ But a couple of things happened; one of them is what happens to a lot of people who were dyslexic. Right around third or fourth grade, I started hitting a wall with reading. I was doing okay, because a lot of words were sight words up until then – it was lot more acceptable for me to be sight-reading before that. Then I got to the point where I had to sound things out, which was pretty much impossible with my dyslexia. Reading became really difficult. So there came a point where I thought I was more likely to go the park and pull Excalibur from one of the rocks than write a book, because reading the way I was supposed to read felt impossible.

“The other side of it was that I just didn’t see a lot of stories that reflected the experiences that I knew – stories that reflected being mixed-race, and that reflected growing up Mexican-American. And as I got older, that reflected the feelings that I would eventually realize was me being queer and being nonbinary. That combination of ‘Reading is so hard for me, so how could I ever actually write in a way that meant anything?’ and ‘My experiences, my family, and my communities aren’t really there, so do we really belong on the shelves?’ that really pulled me back from thinking I could be a writer.

“I actually got back into writing because I had a couple of teachers who were just relentless. They were the ones saying, ‘I know you have stories in you.’ They just worked on me until I showed them something.

“So people around me saw that potential in me in a way that I just didn’t. And that included people in my family. My mom has the experience of being severely dyslexic; she didn’t learn to read until her late twenties, and she’s one of the smartest people I know. Knowing she was dyslexic, and knowing what her experience was, she’d already given me an example of ‘people with dyslexia aren’t stupid.’ We need that. We need each other. Whatever it is, identity-wise, we need people who have been there before.

“I wasn’t officially diagnosed with dyslexia until a few years back. It was one of those things where I said, ‘I have trouble with reading,’ and sometimes people caught on a lot faster than I did, because they thought that was a euphemism: ‘Okay, you’re talking about dyslexia.’ The funny thing was I didn’t mean it as a euphemism, I just didn’t know what was going on in my brain. I hadn’t been officially diagnosed. When I talked with my mom about the diagnosis, she said, ‘Well, yeah. I knew that.’ I said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?!’ She said something like, ‘I didn’t want to make you feel bad!’ So even my mom, who’s incredibly smart, who became an avid reader after not even learning how to read until adulthood, she still had some of that internalized ableism, that thought process that it was somehow going to be to my detriment if I knew that my brain worked differently.

“When I think about being dyslexic in the context of publishing, copyeditors are heroes already, but they’re especially heroes when they work with writers who have any kind of neurodivergence that messes with how we process words, like dyslexia. I already had such admiration for the people I was working with on the production team, and such admiration for my editors, and that was even more so once I realized they’d been working with me and my brain without us ever having had a conversation about it. There are people who will meet you where your brain is at, and that’s just something I’m tremendously grateful for. They’re often the same people who meet me where I am identity-wise, and who are on board with me writing about intersectional identity. I’m incredibly grateful for the people who were helping me in that process when I didn’t even know the full extent of what they were doing.”

EM: “When I think about science fiction/fantasy in the context of writing Venom & Vow, reading Once & Future by A.R. Capetta & Cory McCarthy was a big part of learning how to do a collaboration within a couple – we have a lot in common with them, and they shared techniques with us. That was definitely formative in the writing of Venom & Vow, and also just a great book to mention.”

AM: “He would not shut up about this book when he was reading it. We read it right around the same time so when he would tell me about what part he’d just read I’d be like, ‘I know!”’

EM: “That book was a key part of the creation of Venom & Vow. If we’re talking about earlier stuff, when I was younger, I really enjoyed Eloise Jarvis McGraw’s historical fiction. I read them at a key point where I was like, ‘Someday, maybe, I could write a thing kind of like this. Wouldn’t that be great?’ There was something about the writing that got me really hooked. How does one build a world, and make it feel like you’re presenting a reader with something that grabs them? So during the technicalities of writing Venom & Vow, I thought about what it was like to read that, and how to do the same things.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman

Read the full interview in the August 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.