Ian Mond Reviews The Last Vanishing Man by Matthew Cheney

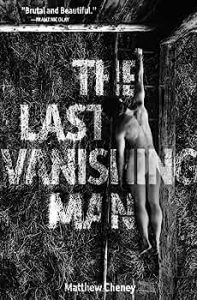

The Last Vanishing Man, Matthew Cheney (Third Man Books 979-8-98661-450-2, $19.95, 308pp, tp) May 2023.

The Last Vanishing Man, Matthew Cheney (Third Man Books 979-8-98661-450-2, $19.95, 308pp, tp) May 2023.

I’ve come to know Matthew Cheney through his brilliant, incisive non-fiction. He spent nearly two decades on his website, The Mumpsimus, discussing everything from Virginia Woolf to Samuel R. Delany to Jeff VanderMeer, with a particular focus on queer writers, especially those a mainstream audience, such as myself, might not be aware of. Amongst so much good work (all archived on The Mumpsimus, with Cheney recently moving over to Patreon), I highly recommend “The Rats in Our Walls: An Essay”, which is both a brilliant deconstruction of the Lovecraft story, but also an attempt to fillet out those parts of the tale that remain useful, free of bigotry and anti-Semitism (that’s a gross simplification of what’s a complex, fascinating piece of criticism). I was also aware that Cheney wrote fiction and had even won an award for his debut collection Blood: Stories, but for whatever reason, I’d never gotten around to picking it up. But now that I’ve read his second collection, The Last Vanishing Man, I regret not approaching Cheney’s short fiction sooner.

The Last Vanishing Man comprises 14 stories – three original to the collection – separated into four sections. Each section – as explained on the back cover— picks out an organising principle common to the stories, whether it be “people seeking to make sense of history and their place in it” or “the quest to understand someone who is gone” or “lonely men seek[ing] meaning in a world where they have lost their way” or, in the final section, “the extremes of feeling, the extremes of strangeness, the extremes of horror.” But the reality is that these themes are consistent across the collection. Take the opening piece, “After the End of the End of the World”, which tells the story of Jane, whose father, Ray, assassinates a Supreme Court Justice by setting off a bomb in a café. It’s a fractured piece of prose, one that forks off into other possibilities, other modalities, but always comes back to a single reality: of Jane alone, standing on a glacier, her life irrevocably changed by the actions of her father. I could take up the entirety of this review excitedly discussing this one incredible story (the narrative shaped into a quantum waveform), but the point I want to make is that the story embodies each of the four organising principles. It’s a tale about history, about extremes (political violence), about lonely men seeking meaning (Jane’s father) and a quest on the part of the unnamed narrator to make sense of Jane’s life (“I have tried to tell her story for over a decade now, but she slips between the lines”).

This isn’t to say that Cheney’s fiction is repetitive. Far from it. The issues he’s addressing are existential concerns that can be viewed from multiple perspectives. The violence perpetrated by Jane’s father, coupled with America’s obsession with guns and gun-related violence, is echoed in several of the stories: “Mass”, “A Suicide Gun”, and “The Ballad of Jimmy and Myra”. All three are extraordinary, but they also come at the topic differently. “Mass”, much like “After the End of the End of the World”, has at its centre a shocking act of domestic terrorism: a lonely, angry man carrying out a mass shooting. But the story, framed around an academic interviewing a professor he has long admired who was also close friends with the shooter, is about much more than just the mass shooting; it’s a tragic story about the death of youthful idealism and the inability to make sustained change. “A Suicide Gun”, as the title suggests, deals with America’s firearm addiction and its insidious effects on the male protagonist. What could have fallen afoul of cliché is instead a heartbreaking depiction of a man’s identity shattering under the weight of his fears and insecurities. “The Ballad of Jimmy and Myra” is a laugh-out-loud, absurdist romp about the titular Jimmy, “who started smoking when he was eight,” and the titular Myra, suffering from terminal brain cancer, who meet at a hospital support group. Their exploits, involving much vomiting, sex, and a killing spree in the Midwest, see them grow a huge fan following. While the story’s message – about how America sensationalises violence and its patronising treatment of impoverished children – isn’t hard to miss, the strange, twisted tenderness between Jimmy and Myra makes the story sing.

I’ve barely touched the surface of The Last Vanishing Man. I’ve not said enough about how gracefully Cheney depicts the melancholy of older gay men who were never able to fully express their affections (“The Last Vanishing Man”, “Winnipesaukee Darling”, “Mass”, “Wild Longing”) and the loneliness and isolation of younger gay men in a post-AIDS world (“Killing Fairies”, “At the Edge of the Forest”). I’ve also not said enough about his speculative credentials. “Hunger” is as good a horror story as you’ll read this year, grisly and haunting with a gut-punch of an ending, while “Killing Fairies” is a master class in magic realism and creepy ambiguity. Furthermore, Cheney’s dystopias, such as the brutal “Patrimony” and the bleak “Of the Government of the Living”, speak to Cheney’s belief (expressed in his excellent essay “Ending the World with Hope and Comfort”) that any dystopias that portrays a tolerable life when the world ends “are not just inaccurate, but despicable” (a view I heartily endorse). While grim and sad, the stories in The Last Vanishing Man are anything but an exercise in misery. There is a genuine beauty in Cheney’s clear-eyed prose, which immerses you in his world, even if the subject matter is challenging.

Ian Mond loves to talk about books. For eight years he co-hosted a book podcast, The Writer and the Critic, with Kirstyn McDermott. Recently he has revived his blog, The Hysterical Hamster, and is again posting mostly vulgar reviews on an eclectic range of literary and genre novels. You can also follow Ian on Twitter (@Mondyboy) or contact him at mondyboy74@gmail.com.

This review and more like it in the June 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.