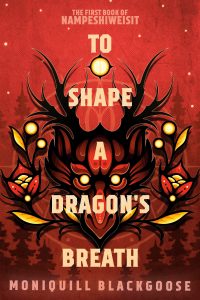

Liz Bourke Reviews To Shape a Dragon’s Breath by Moniquill Blackgoose

To Shape a Dragon’s Breath, Moniquill Blackgoose (Del Rey 978-0-59349-828-6, $18.00, 528pp, tp) May 2023.

To Shape a Dragon’s Breath, Moniquill Blackgoose (Del Rey 978-0-59349-828-6, $18.00, 528pp, tp) May 2023.

To Shape a Dragon’s Breath is Moniquill Blackgoose’s debut novel. Like The Iron Princess, it sets itself in a context defined by colonialism, and the relationship between coloniser and those that they have colonised. Unlike The Iron Princess, the world of Blackgoose’s novel is a recognisable analogue of our own, albeit containing dragons and their fantastic abilities.

Anequs is a young woman from the remote island of Masquapaug, a community of farmers and whalers. Once, when her grandmother’s grandmother was a small child, dragons lived alongside her people, but they disappeared in the great dying that devastated the region soon after the arrival of Anglish settlers from across the ocean. When she sees a dragon fly away over the sea, she’s not sure if it’s real or a vision, but the egg she finds is very real, and a source of joy for the whole community. When the hatched dragon, Kasaqua, immediately bonds with her, she becomes a Nampeshiweisit, a person whose relationship with her dragon is something sacred, full of the potential for change.

To the Anglish colonisers, dragons are little better than expensive trained animals – tools and weapons. They have laws about dragons and dragoneers, and if Anequs cannot fulfil their very specific requirements, Kasaqua will be killed. Anequs is accepted by Kuiper’s Academy, an Anglish school on the mainland (one run by, it becomes clear, the upper-class Anglish equivalent of radicals). There are things about dragons she needs to learn, and every single one of her people who could have taught her is long dead, but her position at the academy is politically fraught – more so than she initially realises – as well as full of social traps. Her upbringing is at odds with the Anglish way of life, she has no formal schooling, and the Anglish look down on her people as ‘‘primitives’’: at best second-class citizens to be assimilated to the ways of their betters, at worst ‘‘savages’’ to be wiped out. Although Anequs is confident in who she is and determined to learn whatever she needs to help her dragon, her coming of age is going to make waves.

Maybe tidal ones.

To Shape a Dragon’s Breath follows the shape of the boarding school story, long a literary staple: the young person enters a world wider than that of the family circle, and in the social microcosm of the educational institution discovers or affirms their values and their place in the world, faced with role models – or anti-models – in the face of their teachers and their peers. Most teachers are indifferent, few supportive, at least one inimical; school peers provide bullies, allies, and a couple of less easily categorised individuals. E.E. Knight’s relatively recent Novice Dragoneer offers a novel that could be read in parallel with To Shape a Dragon’s Breath for very different treatments of outsiders attending elite training institutions with dragons.

Blackgoose uses the social microcosm of the school world to focus on the issue of assimilation and resistance, and the relations of power – cultural, social, and economic – between coloniser and those that they have colonised. The Anglish who want Anequs to succeed want her to do it on their terms, to assimilate their values, and to become – as they see it – ‘‘civilised.’’ This includes headmistress Frau Kuiper, who some forty-odd years before smashed Anglish social convention to become a female dragoneer on military service, and her school colleague (and secret lover) Frau Brinkerhoff: a pair who might be sympathetic were it not for their casual cultural chauvinism. Anequs finds more congenial, if less appropriate in Anglish eyes, allies in Liberty, one of the school’s indentured maids; Theod, a young Indigenous man raised as a servant after the execution of his parents (both the subject of Anequs’s romantic interests); and Sander, one of Anequs’s classmates, whose habits (he presents in many ways as strongly on the autism spec trum) render him something of a social outcast despite his upper-class background.

The school story as a genre is often a species of wish fulfilment. This is also true here, from a certain point of view: Anequs’s certainty in who she is and what she wants from life don’t change greatly despite the pressures of her situation, and her ability to succeed on her own terms and her own merits, even when the entire social context amongst her people’s colonisers is trying to undermine that at every turn, is never seriously in doubt. The question is only (to mix my metaphors and references) whether the Anglish will, like Darth Vader, unilaterally and arbitrarily change the rules if it looks like their perceived inferiors can beat the house. Confidence in one’s own identity and in one’s own place in the world is neither a traditional form of wish fulfilment nor traditional in the protagonists of school stories, but only a very self-possessed, self-confident protagonist could render To Shape a Dragon’s Breath triumphant rather than grim: could make it eucatastrophe rather than noirishly bleak.

Blackgoose is deft with her characters, good at showing the interiority of individuals other than her viewpoint protagonist. That makes their casual cultural chauvinism, classism, willful ignorance, and ‘‘well-intentioned’’* racism even more distressing. The Anglish culture derives from Norse and Germanic influences, with a history of raiding and terrorising, though in the form we see in the novel, it has developed the trappings of our 18th and 19th century’s upper class social whirl, with debuts and dances. One of the interesting things that Blackgoose does in the earlier part of the novel is to have a number of very brief interludes where someone tells a story from their cultural legends: in this way she reveals and contrasts certain attitudes and assumptions from Indigenous and colonial cultures. The attitudes to gender, sexuality, and community are also in contrast.

I would have preferred to see a little more time and attention spent on the Indigenous characters away from the Anglish context. The novel gives little sense of the wider personal and political relationships within the Masquisit community outside Anequs’s family, or among their surviving Indigenous neighbours, and this has a flattening effect. The Anglish, while frequently unsympathetic, come across as complex individuals in a complex, mixed community, one with divisions of opinion and approaches to the world. The reader can see this because Anequs spends so much time navigating the rules and expectations of that community. More focus on the complexities of the Masquisit community, and more space to grow and develop for the characters who have not chosen to interact closely with the Anglish world, would have given the novel greater scope for contrasting these different worlds and the attitudes of the people within them, and ultimately given the narrative more force and power.

The climax involves high social stakes and an assassination attempt, as well as school examinations. It’s tensely explosive and deftly done. To Shape a Dragon’s Breath is an entertaining story and a striking debut. I’m very interested to see what Blackgoose does next.

*They might claim or even believe that they mean well, but they are wrong.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the May 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.