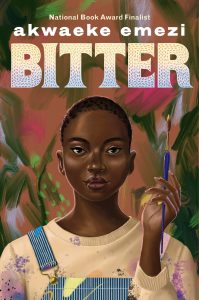

Maya C. James Reviews Bitter by Akwaeke Emezi

Bitter, Akwaeke Emezi (Knopf Books for Young Readers 978-0593309032, 272pp, $17.99, hc) February 2022. Cover by Shyama Golden.

Bitter, Akwaeke Emezi (Knopf Books for Young Readers 978-0593309032, 272pp, $17.99, hc) February 2022. Cover by Shyama Golden.

Content warning: sexual violence, anti-Black racism.

I would be amiss to not begin with the words that Akwaeke Emezi writes in their dedication of Bitter: ‘‘Still and always, for Toyin Salau. You deserved a better world.’’ Toyin was raped and murdered by an older man who assaulted her after offering her a ride back to the church where she had sought refuge due to housing instability.

I’m not sure that anyone can appreciate the depth and richness of Bitter without this background. Named after the protagonist, Akwaeke Emezi’s fantasy novel is about the Toyins of the world, and how their magical abilities are being used and abused to create a better world amidst social unrest. More specifically, our protagonist Bitter, a young woman whose artistic ability may have the power to influence a revolution. Only, she has no interest in it.

The opening conflict of the novel is just that: Bitter is a queer young girl who has an intimate experience with violence and loss – first the loss of her biological mother, and then the violence of a foster family that rejected her entire being. All around her, school shootings, police brutality, and the indifference of the adults meant to protect them grates against her patience and sense of self. With housing insecurity, she is not always sure what home looks like, nor can she always appreciate it. Staying out of other people’s business, after all, is how she survives. As the prequel to Akwaeke Emezi’s Pet, this novel focuses on the birth of the monsters and creatures that emerge in later novels, with an emphasis on Black radical protestors and their means of survival.

After years of abuse, Bitter has found refuge in the artistic haven of Eucalyptus, where she can paint and be herself. Surrounded by her chosen family, Bitter can tune out the protests outside, even as her friends stand on the front lines against corrupt millionaires and violent law enforcement. Even though some of her friends are involved in the protests, she feels an intense anger and resentment towards Assata, the mostly-youthful group of people leading protests every night despite rubber bullets, tear gas, and other forms of violence from law enforcement. She’s constantly reminded of this fact, not just because she lives in the heart of Lucille, but because she seemingly can’t stop running into her former girlfriend, Eddie.

Eucalyptus is her haven. Even more, her newfound privacy means she can explore her gift of bringing small drawings to life with just a few drops of her blood. She’s even begun to fall in love again, with a sweet young boy whose mission in life has become to heal his community from trauma. This comfort makes Bitter restless, though: though her friends are supportive of her decisions, she wonders what the cost is to participate, or to sit on the sidelines.

The novel takes an unexpected turn when the revolution hits too close to home. Embroiled in conflicting emotions, Bitter makes an abrupt and dangerous choice to do something about her situation. The consequences of her decision and use of her gift change the entire tide of the protests and open the book to a new world of monsters and creatures that prey upon her deepest sense of hopelessness and desire for revenge against those her have hurt her and her friends.

Emezi offers some intense discussions about the politics of revolution through the teenagers of the book. Bitter is a small tome, but a mighty one; discussions of the merits of non-violence and personal convictions sprawl across the page in a timely and self-aware manner. As events unfold outside of the characters’ control, they make reckless decisions in the hope of creating a better world. Emezi’s understanding of youthful protestors is both attentive and precise. They are neither idealistic nor are they fully jaded, though they do speak about the exhaustion that plagues many young activists when fighting battles that older generations were supposed to have finished. They center the protestors and radical Black activists, rather than the response of politicians, in a manner that is honest and tender.

The intensity of the plot only increases as more beings and creatures enter the fray. While the leaders of Assata wish to stay non-violent, forces beyond their understanding insist upon righteous destruction. In an unspoken but poignant emphasis, Emezi shows that it is the children of this world who show restraint, despite most of the politicians in their lives showing none. Indifference and burn-out, too, are monsters that Bitter and her friends must confront.

I loved Bitter’s character – her artistry, voice, and convictions were unwavering, despite her fears and her desires to be left alone. Ube, the leader of the Assata movement, was similar in a way that served as a foil to Bitter. As one of the leading voices of the movement, his strength and courage served some of the tensest moments of the novel.

Bitter was an easy read, even with its heavy themes. Like its protagonist, Bitter exudes multitudes: honesty, rage, healing, and righteousness delivered in one smooth reading.

Maya C. James is a graduate of the Lannan Fellows Program at Georgetown University, and full-time student at Harvard Divinity School. Her work has appeared in Star*Line, Strange Horizons, FIYAH, Soar: For Harriet, and Georgetown University’s Berkley Center Blog, among others. She was recently long listed for the Stockholm Writers Festival First Pages Prize (2019), and featured on a feminist speculative poetry panel at the 2019 CD Wright Women Writer’s Conference. Her work focuses primarily on Afrofuturism, and imagining sustainable futures for at-risk communities. You can find more of her work here, and follow her on Twitter: @mayawritesgood.

This review and more like it in the July 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.

“Remiss”: You would be RE-miss not to being with the words…”

a·miss /əˈmis/

adjective

not quite right; inappropriate or out of place.

“there was something amiss about his calculations”