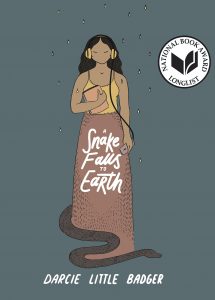

Alex Brown Reviews A Snake Falls to Earth by Darcie Little Badger

A Snake Falls to Earth, Darcie Little Badger (Levine Querido 978-1-64614-092-3, $18.99, 384pp, hc) November 2021. Cover by Mia Ohki.

A Snake Falls to Earth, Darcie Little Badger (Levine Querido 978-1-64614-092-3, $18.99, 384pp, hc) November 2021. Cover by Mia Ohki.

I’ve seen Darcie Little Badger’s A Snake Falls to Earth described as young-adult fantasy and young-adult science fiction, but it’s really young-adult Indigenous futurism. The term was coined by Grace L. Dillon, an Anishinaabe professor and author. In her book Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, she defined Indigenous futurism as encompassing the ‘‘narratives of biskaabiiyang, an Anishinaabemowin word connoting the process of ‘returning to ourselves,’ which involves discovering how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post-Native Apocalypse world.’’ That’s exactly where Little Badger’s exceptional sophomore novel sits.

The story begins with Nina’s Great-Great Grandmother telling a story no one can understand. As Nina grows up, she struggles to translate the story, while also building a following telling her own stories on a popular app. In the Reflecting World, Oli, a cottonmouth snake person, is thrust into the world to live on his own. And he promptly gets lost. He befriends a silent but amiable toad called Ami, an observant hawk named Brightest, and two very energetic coyote sisters, Reign and Risk. Nina deals with a sketchy new neighbor who is harassing her Grandmother while working to figure out what is causing her Grandmother’s mysterious illness; at the same time Oli is trying to avoid a frightening monster. When Ami falls ill, Oli and his friends realize the only way to help him lies in the human world. Saving Ami and Nina’s Grandmother will take hard work and dedication from everyone, human and animal person alike.

Little Badger interrogates how Nina’s Lipan Apache family contends with the environmental and cultural consequences of colonialism. The book is set in the near future, with advanced digital technology and an ever-worsening climate crisis causing too-frequent hurricanes and other devastating extreme weather disasters. On a smaller scale, we follow along as Nina struggles to translate her Great-Great Grandmother Rosita’s final story, told in a language nearly lost over generations of colonization and oppression.

At first, Nina turns to Western science to solve the problem of what is happening to Ami, and to computers and technology to untangle Rosita’s language barrier, but she eventually learns that her Indigenous traditions hold the keys to both. Little Badger digs around in that messy space of how the West often uses the same tools to both destroy and create, and where Indigenous knowledge and practices can interrupt and improve on that. Here, the act of connecting with your ancestors, your place in the world, and your responsibilities as a member of a society are just as important, if not more so, than the flash and triviality of digital distractions. Crucially, Nina’s investigation into her culture and history is not framed as uncovering a buried secret but as learning to see what has always been there.

In a novel full of remarkable things, one of the most remarkable is the narrative itself. Nina’s story uses a rather traditional YA structure, except told in third person rather than first. Oli’s story, however, feels more like a story being told. We never learn who he is speaking to, but it doesn’t matter that much. It’s his story, and we are listening. His story neither begins at the beginning, ends at the end, or fills in everything in the middle. We get pieces told in a chronological order and clearly building to something, but each piece also functions as an independent and complete story. The way Little Badger jumped between Oli and Nina, between first and third person, between mainstream and traditional narratives, is really quite something. It should feel jarring and disjointed, but it doesn’t. It flows seamlessly while also letting the structure act almost like a third main character.

Even the endings – Oli’s, Nina’s, and the book as a whole – show the depth of Little Badger’s vast talent. Throughout A Snake Falls to Earth, Nina and Oli encounter inexplicable things or mysterious animal people, but they never let their curiosity intrude on another person’s life. They recognize that they don’t need to have the answers to all their questions in order to be able to empathize, make wise decisions, or behave in a socially responsible manner. They can be respectful without analyzing or critiquing. Sometimes we can just let things be as they are without demanding ‘‘why’’ and ‘‘how.’’ These are not plot holes or loose threads but a clever, powerful way to bring Little Badger’s cultural storytelling traditions into a Western medium.

If Elatsoe was a ten out of ten, then A Snake Falls to Earth is a solid 11. This book could have been twice as long and I still would have begged for more. Although aimed at a young-adult audience, it has the kind of easy appeal and heartfelt tone that will entice younger kids and older adults as well. Anyone reading or buying YA needs to add this to their shelves immediately.

Alex Brown is a queer Black librarian and writer. They have written two books on the history of Napa County, California’s marginalized communities. They write about adult and young adult science fiction, fantasy, and horror as well as BIPOC history and librarianship. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and access set the foundation of all their work. Alex lives in Southern California with their pet rats and ever-increasing piles of books.

This review and more like it in the January 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.