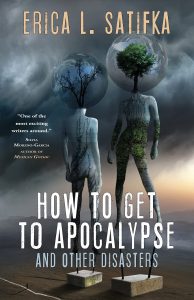

Ian Mond Reviews How to Get to Apocalypse and Other Disasters by Erica L. Satifka

How to Get to Apocalypse and Other Disasters, Erica L. Satifka (Fairwood Press 978-1-933846-17-0, $17.99, 400pp, tp) November 2021.

How to Get to Apocalypse and Other Disasters, Erica L. Satifka (Fairwood Press 978-1-933846-17-0, $17.99, 400pp, tp) November 2021.

In his introduction to Erica L. Satifka’s debut short-story collection, How to Get to Apocalypse and Other Disasters, Nick Mamatas recalls coming across Satifka’s work as co-editor of Clarkesworld while trawling through the slush pile. Coincidentally, it was while scrolling through the social media slush pile that I came across a post from Nick extolling the virtues of Satifka’s first novel, Stay Crazy. I picked up the book and was greeted with a wickedly funny and entertaining story about an evil entity draining the life from the workers at a local supermarket in small-town USA. What marked Stay Crazy out from a glut of fiction where weird shit happens in a rural or suburban milieu is that it provided a frank critique of globalism and an honest depiction of mental illness. I wasn’t the only one who adored the novel, with the British Fantasy Award bestowing Satifka the 2017 prize for “Best Newcomer.” As yet, Satifka has not written a second novel, but she’s kept her toe in the genre pool, submitting her short fiction to online fora like Lightspeed, Shimmer, and, of course, Clarkesworld. Just like Stay Crazy, the 23 stories gathered together in How to Get to Apocalypse display Satifka’s biting sense of humour, her appreciation of the bizarre and surreal, and her concerns, both political and social, at the pervasive nature of neoliberalism.

The first thing that strikes you about Satifka’s short fiction is that she knows how to write a memorable opening sentence. Take the first line from the “The Big So-So” – “We’re both sitting on the rotting front porch one muggy July day when Dorcas asks me if I want to break into Paradise,” or this corker from “Can You Tell Me How to Get to Apocalypse” – “A dozen little dead kids sit on the Styrofoam steps outside the only apartment on Gumdrop Road”, or the elegant opening of “Sasquatch Summer” – “That was the summer the sasquatches came down from Mount Hood and put Papa out of a job.” Importantly, Satifka delivers on these openings. For example, those dead children she mentions at the top of “Can You Tell Me How to get to Apocalypse” are not a metaphor; those are actual dead children. The story she works around them, about a near future where a virus has ended the possibility of child-birth, and the millions who now nostalgically watch a group of rotting dead kids – wired up to CPUs – parade around the set of a rebooted kids show, is as disturbing as it is brilliant.

A common feature of Satifka’s work, which we see portrayed in “Can You Tell Me How to Get to Apocalypse”, is the slow death of society, typically brought about by the rapacious appetite of capitalism (and sometimes alien invaders). In “Human Resources”, people sell their body parts to survive, or in the case of the protagonist, a small piece of her brain so she can afford “a luxury condo and free food for a year.” The main character of “Days Like These”, stuck in an endless virtual environment, questions whether his body is still alive in “meatspace” or whether he is the software remnant of a person and society long extinct. In the visceral “Loving Grace”, an employment lottery decides who will be sliced up and turned into drones to perversely prop up a failing market economy. The best of these – and to be clear, they’re all excellent – is “After We Walked Away”, Satifka’s unflinching response to Ursula K. Le Guin’s seminal short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”. Satifka’s story picks up from where Le Guin ends off, with our protagonists “walking away” from Omelas (or as they remember it: the Solved City) unable to resolve the ethics of a utopia built on the suffering of a child. However, their “moral” choice forces them to confront an outside world that’s fallen into anarchy. In putting her characters through the wringer, Satifka makes the pointed argument, in contrast to Le Guin, that the true evil in Omelas is those who would leave the utopia rather than stop a child from being tortured.

For all the despair and dystopia in Satifka’s fiction, there’s an acerbic thread of humour that runs through most of these stories. Several of them are even out-and-out hilarious. Vying for the award of best title ever, “The Fate of the World, Reduced to a Ten-Second Pissing Contest” is about a bar that’s been stolen by a group of reality-hopping aliens with mouths that resemble anuses. Then there’s the madcap shenanigans of “Trial and Error” (Satifka does like a pun), which is a sequel to “The Big So-So” and sees the ragtag musical group of Syl, Frank, and Clem stuck in Iowa where Frank is faced with a murder charge. If he’s found guilty by the judicial musings of an old Dell computer, he will be literally drawn and quartered. The story that had me laughing the most was “Where You Lead, I Will Follow: An Oral History of the Denver Incident”. Structured around a series of documentary-style interviews with the individuals involved or affected by the “incident,” the piece chronicles the popularity and alleged Russian hacking of a Pokemon Go-like mobile game called “Follow the Leader” which led to the accidental nuking of Denver. While I can take or leave Satifka’s piss-take of Russia’s involvement in American politics, it’s a spot-on satire of our obsession and addiction to mobile games. There are so many other terrific stories – I could speak rapturously about “Automatic” (the piece Mamatas plucked from the Clarkesworld slush pile) and “The Goddess of the Highway” – but I think it’s best that you immediately purchase a copy of How to Get to Apocalypse and discover these treats for yourself.

Ian Mond loves to talk about books. For eight years he co-hosted a book podcast, The Writer and the Critic, with Kirstyn McDermott. Recently he has revived his blog, The Hysterical Hamster, and is again posting mostly vulgar reviews on an eclectic range of literary and genre novels. You can also follow Ian on Twitter (@Mondyboy) or contact him at mondyboy74@gmail.com.

This review and more like it in the December 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.