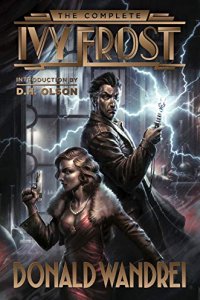

Paul Di Filippo Reviews The Complete Ivy Frost by Donald Wandrei

The Complete Ivy Frost, Donald Wandrei (Haffner Press 978-1893887619, 720pp, $49.99, hardcover) December 2020

The Complete Ivy Frost, Donald Wandrei (Haffner Press 978-1893887619, 720pp, $49.99, hardcover) December 2020

Haffner Press has been gifting the world of bibliophiles and literature-lovers with enormously attractive and highly readable books since 1998, when they published Jack Williamson’s The Queen of the Legion. (For a complete record of their offerings, visit their ISFDB page.) Any publication from Haffner exemplifies craftsmanship, graphic design ingenuity, and attention to textual fidelity. Moreover, they have the good taste and a reverence for the genre’s history that allows them to resurrect key tales and seminal authors. Their exhaustive researches uncover many treasures. I often think that if anyone asked me to convey what was best about the small press scene, the special things they do that the Big Five don’t, I could just mutely point to any volume from Haffner and satisfy the questioner.

Until now, Haffner’s most recent project was 2017’s essential two-volume collection of Fredric Brown’s mysteries. Inevitable circumstances both corporate and global made for a few glitches in the arrival of books scheduled after that, with necessary retrenching. But now Haffner comes roaring back in brilliant form with The Complete Ivy Frost by Donald Wandrei. Just for a start, this lush compilation at a very reasonable price features beautiful endpapers of pulp magazine covers, as well as new interior illos by Chris Kalb that consort well with the contents. A splendid and affectionate introduction from D.H. Olson (who had a personal friendship with Wandrei) kicks off the actual adventures.

What we have with these tales from pulp’s heyday, in the person of I.V. Frost, is a scientific criminologist who exists somewhere on the spectrum from Doc Savage to Sherlock Holmes, from Arthur Reeve’s Craig Kennedy to Ernest Bramah’s Max Carrados. The popular literature of the ’30s and ’40s was replete with these oddball investigators who gave the Black Mask noir guys some steady and formidable competition. Their cases were outré and bizarre and not anchored in pure naturalism in the style of Chandler et al., however mannered that mimesis might be.

In the case of Frost, he does not deal in the supernatural per se, explicitly stating that he is agnostic about the occult: it might exist, but he’s never seen it. So we can’t conflate him with that crowd recently profiled in Mike Ashley’s Fighters of Fear, although he remains a cousin. But rest assured that although these adventures all obey the laws of physics and human psychology, they plumb the limits of those fields in thrilling and outrageous ways.

A prior assemblage of a fraction of the Frost cycle appeared in 2000 from Fedogan & Bremer, and I reviewed it in the pages of Asimov’s. But that was 20 years ago, and represented a mere handful of the total of 18 tales. After such a long interval, I gleefully plunged back again into those adventures I had already read and enjoyed them a second time, before moving onto those new to me. I can’t synopsize each one here, but let’s hit some standouts.

The first entry, titled simply “Frost”, does a great job setting up everything for the whole series, as well as providing its own mind-blowing escapade involving a kind of Moriarty-style gangster. Frost’s first client is glamour girl Jean Moray, who goes on to become his assistant for the rest of the adventures. Jean is not only heart-stoppingly beautiful, but also clever, brave, ingenious, bold, and willing to tackle any assignment, however inexplicable. Far from a cardboard cutout, she emerges as a fit companion and foil for Frost, matching him move for move, even frequently tweaking his pride, although she is still a few orders of magnitude below his powers of ratiocination. And admittedly, she cannot look upon corpses with quite the same dispassionate equanimity as Frost does.

“Bride of the Rats” is a good illustration of how these stories differ from the Black Mask kind. Hammett might have conceived of a Bluebeard-type serial killer who married and murdered numerous brides, but he would definitely have failed to include a booby-trapped castle with a dungeon full of hungry rodents and the skeletons of all the brides.

Frozen corpses fall from the sky and shatter in “Death Descending”. A gruesome amusement park is the venue for “Merry-Go-Round”. Jean and Frost face death by steamroller (shade of Roger Rabbit!) in “Bone Crusher”. Seemingly contagious manias break out in “The Lunatic Plague”. A bit of a Wellsian aura (The Island of Doctor Moreau) clings to “Giants in the Valley”. Corpses pop up in a department store setting in “A Beetle or a Fox”. And finally, in the concluding and conclusive tale, “Electric Devils”—which might remind you a little bit of the first Superman serial from 1948—Wandrei brings Frost’s career to a literally explosive, bravura terminus.

After even a couple of these tales, we begin to see Wandrei’s method: he presents a series of events seemingly impossible, baffling unconnected, or possibly counter to natural laws. But Frost—who sees the hidden patterns—and Jean Moray surge ahead regardless, often facing mortal dangers, assembling all the pieces of the puzzle until a perfectly logical answer and solution—often involving rough justice—takes place. The tales often possess a florid surrealism in the manner of certain other pulp adventures involving the Spider, and they display plenty of Grand Guignol gore.

As with all pulp serials, talismans repeat from story to story in a comforting manner. Frost always smokes his queer homemade cigarettes. Jean always gets irked at Frost’s cold-bloodedness. Inspector Frick of Homicide shows up to lend a puzzled hand. But Wandrei is such a good artist, not a mere hack, that he varies the touchstones. In one story, we watch Frost assemble his smokes from scratch, and learn the recipe. Jean’s aversion to Frost turns to affection and unrequited love. Unlike the official lawman nemeses of the Saint and Holmes and other detectives, Frick actually regards Frost as his superior and gives him every assistance. Sometimes Frost and Jean are on the case from the opening sentences. Other times, as in “Blood in a Golden Crystal”, they don’t show up until part 3 of the novella.

In addition to his superb and tricky plotting abilities, Wandrei possessed awesome gifts for scene-setting, conjuring up vivid environments and moods easily. From “The Artist of Death”:

It was a cold, blustery morning, more like early winter than early spring. Gray clouds shrouded the sky. The wind whipped in from the Hudson. It whirled eddies of dust and bits of paper debris along the Drive. It blew around corners with great, irregular gusts that made walking hazardous. A man hiked after his gray fedora that skimmed away in long arcs like a jack rabbit. A woman started to turn the corner from State Street but the wind blew mightily. Her coat bellowed [billowed?] and she was forced back a few steps. She leaned against the wall of wind. It stopped blowing suddenly and she almost fell. She reached the turn and staggered weirdly as the wind yowled again. The police car nosed along State Street and eased to the curb in front of Number 13. A blown sheet of newspaper slapped against the windshield, lay flat there for a moment under the pressure of wind…

These stories could serve as models for anyone writing thrillers or novels of suspense. The action is fluidly non-stop, leaping from one unpredictable set-piece to the next. A few of the villains are normal humans pushed to extremes, but most are stone-cold sociopaths or psychopaths. Occasionally there is a Jack Vance edge of punctilio to the dialogue. But there’s plenty of authentically demotic speech too. (The only corny bits are a stage Englishman in “A Beetle or a Fox”.) Moments of quiet reflection are generally assigned to Jean—and large parts of the book are told from her POV—but Frost offers plenty of philosophical observations to complement the action, either to Jean and Frick, or when putting the bad guys in their place.

Cinematic influences are apparent. One could easily imagine any of these stories as a 70-minute B-movie from Warner Brothers or RKO. Despite their age, they deliver undimmed pleasures.

Cofounder of Arkham House, a dedicated and clever fictioneer, Donald Wandrei still, nine decades onward from these tales, can command our attention like a maestro and reward us prodigiously with frissons and amazements. He fully deserves this handsome revival.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.

I see that all of these stories were published over a span of three years in “Clues Detective Stories.” And the editor of that magazine was … F. Orlin Tremaine, who at that time was also at the helm of “Astounding.” So there…