Adrienne Martini and Russell Letson Review A Desolation Called Peace by Arkady Martine

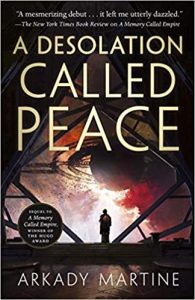

A Desolation Called Peace, Arkady Martine (Tor 978-1250186461, $26.99, 496pp, hc) March 2021.

A Desolation Called Peace, Arkady Martine (Tor 978-1250186461, $26.99, 496pp, hc) March 2021.

Despite how many readers raved about it, I didn’t manage to read Arkady Martine’s multi-award winning A Memory Called Empire when it first came out. There is never enough time, you know? But when the follow-up – A Desolation Called Peace – hit my in-box, I read the first few pages and was so hooked that I went back to hoover up A Memory Called Empire before diving into A Desolation Called Peace. I regret nothing, mind, but do want to note that the first book was still fresh in my mind when I read the second book.

A Desolation Called Peace picks up a couple of months after the events of Empire. Mahit is back on Lsel station, Three Seagrass is in Palace-Earth, and the new emperor is on the throne. Mahit is trying to process all of the events of the previous book when she is quickly thrown into a new situation that forces her to make a hard choice and figure out who her allies are. Of course, her path forward becomes even more muddy when Three Seagrass shows up on Lsel Station (and the scenes of Three Seagrass attempting to parse Stationer culture are some of the most amusing in the book). A war with an unknown species is breaking out and the pair need to get involved. Back on Palace-Earth, political schemes are poisoning the decision-making process, and the very young heir to the throne is in the middle of them.

If that makes no sense, I recommended do as I did and picking A Memory Called Empire up right this very second. Seriously. It’s great.

Fortunately, A Desolation Called Peace is also great, even though it is a different sort of story than its predecessor. The first book was a kind of coming-of-age tale; this one is about what makes a civilization and how to reconcile the continual push and pull between protecting yourself and showing vulnerability. And both are about the irresistible force of Empire, which lures you in while ensuring you know your place.

—Adrienne Martini

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

No matter how the blurbs wind up categorizing Arkady Martine’s second novel, A Desolation Called Peace, no single genre label will quite capture it, because every time you look at it from a different angle, it changes its configuration – all the while feeling like a single, wide-ranging story whose parts belong together.

Of course, any narrative is constructed out of parts to be found in the Big Box of Story Components – tropes and motifs and enabling devices and ideas and traditions – but the magic is in the hands of the builder. Some of the elements that Martine is deploying in this novel (and in its 2019 predecessor, A Memory Called Empire) have also featured recently in work by C.J. Cherryh, Walter Jon Williams, Elizabeth Bear, and Ann Leckie, resulting in an identifiable subgenre-ish body of work that might be called the space opera of manners, or the anthropological adventure, or the tale of imperial intrigue, or First Contact, or bildungsroman, or even SF romance, depending on the angle of view. Or maybe I’m just letting my taste for taxonomy and Venn diagrams get out of hand. In any case, Martine, like her colleagues, has built a story space (or a space-story space) that accommodates a complex set of narrative lines, character arcs, and genre machineries that get highlighted as the plot turns to reveal the book’s facets.

The title is drawn from a famous line from Tacitus in which a Celtic “barbarian” characterizes the pax Romana: “they make a desert and call it peace.” Like imperial Rome, the interstellar Teixcalaani empire is relentlessly expansive, elaborately hierarchical, extractive (of its conquered territories), and extremely well organized. Its legions maintain order and unity, often by bloody means, though it hasn’t deployed “massive planetary strikes” for centuries. But now warships and frontier colonies are being wiped out by an undetectable alien enemy that “struck, destroyed, vanished without warning or demands,” out in the sector near the territory of fiercely independent Lsel Station.

Five major viewpoint characters occupy four converging plot threads, each viewpoint operating in third-person-close mode, so we share a character’s stream of thoughts, doubts, and emotions. (There are also Interludes in which we enter other viewpoints, including one that only gradually comes into clear focus.) Teixcalaani Fleet yaotlek Nine Hibiscus (whose rank I read as “admiral” with overtones of “theater commander”) and her second-in-command Twenty Cicada confront an enemy that is not only technologically equal or superior but also uncommunicative and enigmatic. Nine Hibiscus is a supremely competent and successful commander – so successful and so beloved by her troops that there are those in the government who would not mind seeing her die heroically out on the frontier. And she finds among her own forces a captain who seems to be serving that faction.

On Lsel Station, there are some who would not mind seeing Teixcalaan’s forces grind away at an endless war against inscrutable aliens instead of absorbing Station territory and resources and culture. In fact, very green ambassador Mahit Dzamare (carrying two copies of the imago – the recorded memories and personality – of her predecessor in a brain implant) was part of the process by which the empire was alerted to the threat on their frontier. On Mahit’s return to Lsel Station, local politics are making her life more than uncomfortable, since one Councillor intends to remove Mahit’s imago-machine and maybe arrange a fatal surgical accident in the process.

On Teixcalaan’s capital world, the imperial heir, Eight Antidote, is a serious, curious, bright 11-year-old boy exploring the world he is being trained to rule – currently tracing the physical tunnels and back ways of the palace complex while observing the operations and rivalries of the imperial bureaucracies and departments. Elsewhere on the capital, Mahit’s one-time government (and potential personal) liaison Three Seagrass is now Third Undersecretary to the Minister of Information and not entirely happy with her “exquisite prison of an office.” So when she spots an emergency request from Nine Hibiscus, she snags the assignment of “first-contact specialist with diplomatic chops” and then takes the really adventurous (or dangerous) step of traveling to Lsel Station to recruit Mahit as a linguistic-diplomatic advisor, even if the stationer is a barbarian and possible security risk.

The story lines rotate through several genre territories: Nine Hibiscus’s tactical and military-political problems; Mahit’s need to escape the attention and schemes of hostile station politicians; Three Seagrass’s desire to escape a bureaucratic treadmill and to find her way to Mahit; and Eight Antidote’s growing grasp of the logistical and political machineries (and their accompanying intrigues) he will eventually inherit. And when Mahit and Three Seagrass are reunited, we also get to observe a cross-cultural love story from both sides. Meanwhile everybody, with their particular skill sets and predispositions, grapples with the overarching problems of communicating with very dangerous and very alien aliens and deciding whether, when, and how to wage war on them – all the while uncovering hidden and obvious agendas and untangling conflicting loyalties.

Back in 2019, I wrote that A Memory Called Empire was in part about belonging – having or finding or making a place for oneself in a cultural framework. It did so by juggling the roles of memory (personal-organic and recorded-implanted), tradition, and literary/artistic culture in holding together a polity or a personality. A Desolation Called Peace elaborates that theme, but with more attention to personal relationships and social role and identity. When it’s not about space war and political intrigue and strange aliens, it’s about connection, personal and institutional and cultural and perhaps more. Mahit and Three Seagrass; the yaotlek and her adjutant; Eight Antidote and the emperor; even the Lsel Station councillors with their implanted memory-lines and station history and stubborn independence – all come up against the limits of their roles and cultural frameworks and individual emotional makeups. At stake is the big-picture choice between desolation and peace and the character of the empire, but that fate is built up from the actions of individuals facing the mysteries of the Other – as well as the mysteries of each other.

–Russell Letson

This review and more like it in the April 2021 issue of Locus.

Adrienne Martini has been reading or writing about science fiction for decades and has had two non-fiction, non-genre books published by Simon and Schuster. She lives in Upstate New York with one husband, two kids, and one corgi. She also runs a lot.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud MN. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.