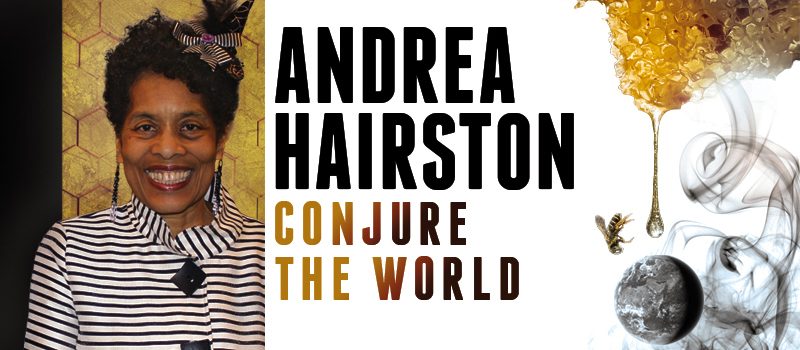

Andrea Hairston: Conjure the World

Andrea Hairston was born July 9, 1952, in Pittsburgh PA, and lived there until she moved to Massachusetts to attend Smith College at 18, where she studied physics and math before switching to theater. She did graduate work at Brown, and has taught theater in the US and Germany. She is currently the Louise Wolff Kahn 1931 Professor of Theatre and Africana Studies at Smith College, and the Artistic Director of Chrysalis Theatre.

Her debut novel Mindscape appeared in 2006 and won a Carl Brandon Award. Redwood and Wildfire (2011) won Tiptree and Carl Brandon Awards, and Will Do Magic For Small Change (2016) was a finalist for Mythopoeic, Lambda, and Tiptree Awards, a Massachusetts Must Read, and a New York Times Editor’s pick. Her latest novel is Master of Poisons (2020). She is also a playwright, with work produced at Yale Rep, Rites and Reason, the Kennedy Center, StageWest, and on Public Radio and Television. Some of her plays and essays were collected in Lonely Stardust (2014).

She has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. She won a Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts in 2011.

Excerpts from the interview:

“I read before I went to school. You could get a kid’s library card if you could write your name, so I got my card when I was around four. My mother was a big supporter of reading. Once I was old enough to get a grownup library card, I started taking out five or six books a week. I consumed books – it was like food. My older brother was a big reader, too. He would read all the books I read, plus all his books, and then wanted to talk about them, so I had to read his books, a lot of fiction and non-fiction. He was a big science fiction and fantasy fan, and had a collection of comic books. I read his comic books and then we argued over them. I mean he even read the encyclopedia – a serious nerd before that word was so big.

“I was the science geek – my brother was actually the word person. He eventually became a newspaper editor for New York Newsday. He appreciated science, so we observed bugs and talked about stars, and science fiction was our joint connection. He died young of a heart attack in 2002. I published ‘Griots of the Galaxy’ in Nalo Hopkinson’s anthology So Long Been Dreaming in 2004, and an excerpt of Mindscape in Sheree Renée Thomas’s Dark Matter: Reading the Bones anthology the same year, so it was sad that he passed away two years before I started publishing science fiction. But I had a whole career as a playwright before that, and all my plays were science fictional or antirealist, so he got to appreciate that. Right before he died, he gave me this huge box of science fiction books and said, ‘This is what I’ve been reading since I saw you last. You’re the one who’ll appreciate these.’ That was amazing.

“As kids, we read Heinlein, because I grew up in the ’50s and ’60s. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress – also Stranger in a Strange Land, and he read a lot of short stories, like Philip K. Dick, so I read him too. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, those hard science fiction things. By the time I got to college, it was the ’70s, and I was reading Ursula Le Guin. The Dispossessed – that really possessed me. I went through all of Le Guin: The Left Hand of Darkness, The Word for World is Forest. I was a big Star Trek fan, so I devoured the novelizations, and then read Vonda McIntyre’s Dreamsnake. By the ’80s I was writing and directing plays with Chrysalis, and all the theater people I knew were saying, ‘You should read Octavia Butler.’ Kym Moore was directing one of my plays and for opening night she gave me this book and said, ‘You need to read Kindred.’ I was like, ‘Whoah, who is this?’ In the early ’90s, playwright Pearl Cleage left me her copy of Parable of the Sower and I read it that night. The reason I went to Clarion West in 1999 was that Octavia Butler was one of the workshop leaders. I met Vonda McIntyre because Clarion West is in Seattle and she was a founder, a big booster, and she threw a party for the workshop. So it all worked out.

“I decided to write science fiction novels in 1995, when I was a guest professor at the University of Hamburg. In theater I’d done antirealism, which is different from science fiction and fantasy, but definitely a cousin or an uncle, so I felt at home. For me, theater is always about having an

experimental space where you define the rules, create a world, and then you play it out and see what happens. Science fiction and fantasy really fit that mindset. I’d learned German because I was interested in German theater and playwrights like Brecht who talked about the ‘Verfremdungseffekt,’ which is what SF people refer to as the distancing effect. Brecht saw that effect as an essential part of epic theater – he wanted audiences to bust out of the status quo, to get beyond the illusions of realism. Brecht wanted people to re-view their world. He wanted plays to make the invisible visible. That was a big part of expressionism in German theater: skew the frame, shift the view. But it’s not emotional distancing. You’re emotionally connected, but the distancing allows you to rethink your world and not take Empire normal for granted, for truth.

“I was in Germany before the Wall came down and then right after, when they had an open door. Refugees came from all over. So I was teaching people from everywhere in a foreign language. I felt like an alien. I mean I got a real experience of being distanced, as an African-American in Germany – I wasn’t met the way I expected to be. Germans weren’t mirroring my own internal image of myself back to me. That doesn’t mean they weren’t racist or weird, but it wasn’t American racism, so I would stand back and think, ‘That’s really strange. Nobody at home would ever do that.’ People kept saying, ‘You’re a typical American.’ I did not see myself as a typical American. But people in Hamburg did and they kept saying ‘typisch,’ or ‘fast italienisch!’, which means ‘almost Italian.’ I told my Bavarian friends, and they said, ‘Oh, Bavarians are almost Italian too, because they’re southern, very friendly and very emotional and they move their hands a lot.’ Not a good thing, not believable to North Germans who wonder if anybody is really that emotional, if anybody should be that blunt. I said, ‘You folks have obviously not spent time with African-Americans, because we speak our minds and do emotions and hand talk fine on our own – we don’t need to be Italian to do that.’

“In Munich, the capital of friendly Bavaria, an older woman, a total stranger, came up to me in a beer garden and told me to watch my bag, and I said, ‘Why should I watch my bag?’ She pointed to some people and said, ‘Yugoslavians.’ I said ‘Why should I watch my bag around them?’ She patted my hand and said, ‘You’re a hard working university student, so you don’t get it,’ and then she spewed all this ethnocentric weirdness about Yugoslavians. I said, ‘Wow, and how can you even tell that they’re Yugoslavian?’ All the people in the beer garden just looked, well, like white people to me, so, the women went into the fine points of the various kinds of white people (which I confess blurred and fizzled in my mind) and repeated why I had to watch my bag around the Yugoslavians – because of course white people aren’t all the same – even if I couldn’t tell the French and the Belgians, and the Germans from the Yugoslavians. It was amazing to be outside my own frame of prejudice. An excellent experience. “So it was in Germany that I decided, ‘I have to write science fiction,’ because living in another language, in another culture, I got the alien experience. I was ‘fremd,’ the German word for ‘strange’ and ‘alien.’ I had always been a science geek – even though I ran away to the theater, I kept up with my interest in nature and physics and all that, so it felt like I was called to the genre. Fantasy called me as well, because I’m a poet and I like the flights of metaphorical thought that are at the heart of a good fantasy, where you have an amazing idea or image that you can use to open yourself to a different horizon. While I was in Germany, I wrote a novel that was basically just worldbuilding for Mindscape, my first published novel, but I didn’t understand this at the time. When I got back to the USA I wrote a few chapters of Mindscape in the world I’d built and a friend said, ‘We should apply to Clarion West,’ and we both got in. It was a sign, like, ‘Okay, these things are all pulling me in a great direction.’ So I went and here I am now.

“I don’t feel the enormous divide between SF and fantasy, or science and the spiritual. There are marvelous insights that each worldview has, and there’s a place where they overlap. Grace Dillon is a good friend of mine and an inspiration, and has done wonders with indigenous futurism and indigenous science and with supporting indigenous SF and fantasy. A lot of people feel like indigenous ancestor wisdom is just superstition and that it’s incompatible with science, but there are many superstitious scientists, and very scientific people who have not gone to MIT, but are methodical, understand their world, and have insight. The notion that non-Western people are completely superstitious, so we can’t trust any of their wisdom, is horsecrap. People wouldn’t survive if their insights into the universe, their cosmology, didn’t work. You can’t base your worldview on things that actually don’t work, that are completely false, because if you did, when you put your ideas in practice everything would go wrong all the time. All of these social realities and civilizations that have gone on for so long could not exist if stupid superstition was all they had. The idea that the knowledge of indigenous people is totally worthless and only Western science is valuable is one of those disinformation campaigns. The hubris is profound. I feel very humbled, as someone who has studied physics, with the vast amount we don’t know. I’ve also studied West African griot storytellers, and I’m amazed by the vast amount of knowledge they’ve incorporated in their verses, about plants, animals, time, water, human nature, trees, everything – and they got it in rhythm and rhyme. A griot knows a library of things by heart – so I am humbled. We all do magical thinking, where you believe what you want to believe. Scientists do that, and non-scientists, too. It’s a tribute to our humanity to assume that there is wisdom everywhere. I have to discern which wisdom I can use, or which wisdom will work, or which wisdom will carry me, will conjure the world I want, and that’s a difficult task. Some of it will be bunk or poison, so I have to figure that out. But if we had listened to native people about controlled burning in California or Australia, we might not have some of the climate-change issues we have now. Discernment is what we need, not a blanket decision to outlaw practices that have allowed people to sustain themselves in a given environment for millennia. I want to be mindful of that, even as I think about the amazing things we have discovered in Western science. We need all the wisdom there is, if we’re going to survive ourselves.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Arley Sorg.

Read the full interview in the January 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.