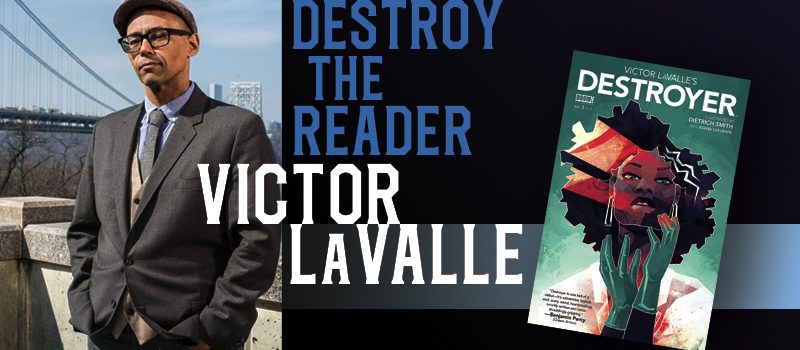

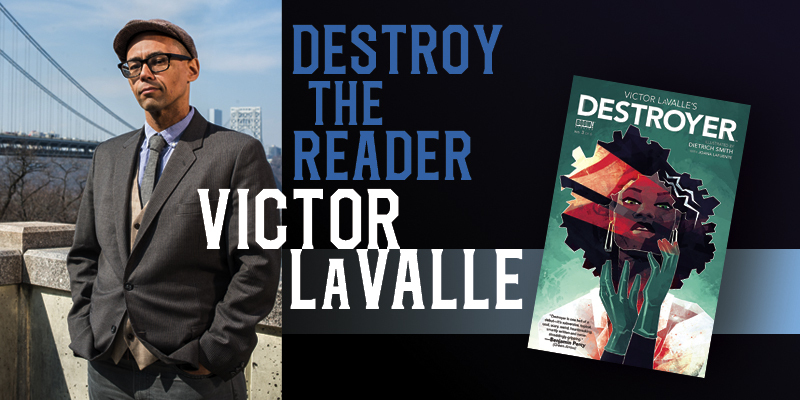

Victor LaValle: Destroy the Reader

Victor LaValle was born February 3, 1972 in Manhattan and grew up in Queens. He earned an English degree from Cornell University and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from Columbia University.

His debut collection was Slapboxing with Jesus: Stories. (1999). First novel The Ecstatic was published in 2002, followed by Shirley Jackson Award winner Big Machine (2009), Shirley Jackson Award finalist The Devil in Silver (2012), and World Fantasy and British Fantasy Award winner The Changeling (2017), also a Shirley Jackson Award finalist. Lovecraftian novella The Ballad of Black Tom (2016) won British Fantasy and Shirley Jackson Awards and was a finalist for Hugo, World Fantasy, Sturgeon Memorial, and Nebula Awards. He also wrote Bram Stoker Award-winning graphic novel Victor LaValle’s Destroyer (2018). He has published several genre stories, including Stoker Award winner “Up from Slavery” (2019). In addition to writing, he teaches at Columbia University.

LaValle lives in Manhattan NY with his wife and children.

Excerpts from the interview:

“The first book that stands out in my memory as important, foundational, is an old version of Peter and the Wolf that my mother used to read to me. It had a particularly vivid illustrated wolf inside. That was the first bit of reading that mixed fear and interest at the same time, and it was the book I asked my mother to read to me the most. I didn’t give a damn about Peter, and I didn’t care if the nice animals won – I loved the wolf, the menace of it, and the power. If I think of myself as a particular type of genre writer, it’s a horror writer, and that was the beginning of me loving horror and everything horror can do.

“I’m a big Godzilla fan. I don’t trust anyone who isn’t. I fell in love with him sitting at home watching Godzilla vs. Mothra, Godzilla vs. Rodan, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, King Ghidorah, all those things. I loved the worldbuilding – every part of Japan and its surrounding seas had these different creatures, and you got the sense of this deep well of time that all these creatures had sprung from. I wouldn’t say I understood it this way at the time, but it felt like watching a subconscious spit out ideas. Many of them were not great, some were forgettable, but Monster X was the most nightmarish creature I could ever think of – not just the look, but that chilling sound it made as well.

“I also simply loved the joy of pure destruction. Even the modern Godzilla movies make the woeful mistake of spending all this time on human beings. Who is coming to Godzilla movies for the humans? As an adult, I understand those movies would cost $300 million if it was just Godzilla fighting all the other creatures for two hours – but I would be in heaven. Kids love Godzilla so much. They really identify. We have two boys, seven and nine, and our older one will say sometimes, ‘Dad, can I goon you?’ I’ll say, ‘Okay,’ and he just comes at me like Godzilla trying to wreck a mountaintop power station. I let him attack the power station for a minute or two, and he walks away happy, like Godzilla swimming back into the ocean until his power is needed again.

“My mom and dad divorced before my memory begins, so my mom and my grandmother raised me. My mother is an immigrant from Uganda, and she was working all the time. It was not a big reading household. The big book in the house was the Bible; my grandmother was very religious, a Ugandan Episcopalian, which we like to joke is double Catholic. The Bible and the Encyclopedia Britannica were the only books that remained permanently in the apartment.

“After those early books my mom read to me, I was left on my own, but I wasn’t limited in any way. If I asked mom to buy comic books for me from the spinner rack at the Gina Rose candy store, she’d say, ‘Okay, you can get a dollar’s worth’ – and that was five or six comics, so I could just dive in. When I got a little older, we were at the pharmacy and they had the spinner rack with the mass-market paperbacks – I’d say, ‘Can you buy me a book?’ As long as the cover didn’t have something she found objectionable, she would.

“Romance wouldn’t work because the covers had men and women lusting for each other, and spy books had guns or tanks on the cover, but ’80s horror was in its boom, and those covers were usually innocuous. They’d have a house with a strange light in the window or a cat with one eye, that kind of thing. Stephen King’s Skeleton Crew just has a toy monkey on the cover – that was fine. That’s how I became a horror writer: those were the covers my mom found acceptable. Maybe I would have become a romance writer or a thriller writer if she had let me read those.

“I was maybe 11 or 12, reading these books, and I wanted to mimic the experience I was having. I loved those stories and I thought, ‘Maybe I should to try write one of these stories and scare my friends, or scare myself.’ It began with me just copying. Stephen King was, of course, popular then (as now), so I often mimicked his stories. His prose is also deceptively simple and clear; he’s not a flowery writer and his narratives are usually relatively straightforward.

“I would take his stories set in Maine, in some working-class white town, and I just rewrite them in mixed-race Queens, ethnic Queens, or make them about a Black family in Queens. It was literally like, if you knew the Stephen King story, you’d say, ‘Oh, you stole that, and just moved it from Castle Rock to Queens.’ But since it was in Queens it was about me and my friends, and the kids were Black and brown and Asian – that was that. If I copied his stories about adults, I didn’t know much about adults, so those usually stayed middle-aged white guys.

“The Ugandan community in New York and New Jersey is very close and everybody knew each other because it’s also not a very big community. On some level they had all helped each other get to America. My grandmother and my mom were among the first to come here in the ’70s or late ’60s, so my grandmother sponsored a whole bunch of people to come over, and then they sponsored people, and that was how it worked to build a community.

“I always felt deeply enmeshed in the community, and yet what’s also true is, you’re only considered Ugandan if both your parents are Ugandan. You’re not Ugandan if they’re not. It’s a patrilineal society, so you are definitely not Ugandan if you can’t say what tribe your father is from. My father was a white guy from Syracuse, so he had no tribe that mattered to Ugandans. I always felt welcome – nobody ever said, ‘You’re not really Ugandan’ or anything like that – but my grandmother and mother didn’t teach me and my sister Luganda, which is their language. Their feeling was, ‘We came here to the US, so you’re Americans.’

“But also – and I don’t think they would have said this or consciously thought it – the other message was ‘You’re not fully Ugandan, so why would you learn Luganda?’

“That feels like a loss in retrospect; I would love to speak the language, and of course I could always learn now, but I’m not going to. I’m working hard enough just to learn Spanish. I felt very much a part of my Ugandan family, but I wouldn’t necessarily say I felt Ugandan.

“Queens was such a mixed-ethnic place that I didn’t feel I had to pick a side early on, black or white I mean. I was mixed, and there was no question I was mixed, but I had a Persian friend, a Korean friend, a Colombian friend, Indian friends, Irish friends, Swedish friends, whatever. If the community had been more explicitly all one thing or another, as a mixed-race kid, I might have felt the need to ‘pick a side,’ or even a desire to belong to one side or another. But there were no sides in Flushing. Or, to be more precise, there were two dozen sides. No one had the numerical advantage. It was an ethnic stalemate! I loved being around so many different kinds of people. I only realized how lucky I was once I’d grown up.

“In the junior high years, you start to think about where you belong, and suddenly these questions of identity, ‘Well, what do I really consider myself?’ became more explicit, where before they were more implicit.

“For a number of my books, I have a main character who is mixed, and one of his parents is Ugandan. The mother is Ugandan, so I’m making up nothing in those cases. At a certain point I came to grips with or understood that I was not Ugandan – I was an American, so what did that mean for me? America often says, ‘You’ve got to pick something – you can’t be many things.’ Whatever that is – Republican, Democrat, left, right, Black, white, whatever it is – this country doesn’t do very well with nuance. In high school we moved from that very mixed ethnicity area to another part of Queens called Rosedale, which was Black – Black American, Black Caribbean, Black African – and that was the moment when I felt like, ‘If America is telling me I’ve got to choose, this is what I choose: I’m Black. I’m a Black American.’ I have never regretted that choice.”

Interview design by Steven H. Segal. Photo by Teddy Wolff.

Read the full interview in the November 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.