Ian Mond Reviews Red Pill by Hari Kunzru

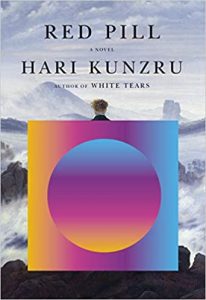

Red Pill, Hari Kunzru (Knopf 978-0-451-49371-2, $27.95, 304pp, hc) September 2020.

Red Pill, Hari Kunzru (Knopf 978-0-451-49371-2, $27.95, 304pp, hc) September 2020.

The narrator of Hari Kunzru’s provocatively titled new novel, Red Pill, is an unnamed academic and freelance writer suffering from a mid-career crisis. When the prestigious Deuter Centre selects him for a three-month residency at their villa in Berlin, he accepts the invitation. It’s not only an opportunity for him to work on his latest project (“I had decided to write about the construction of the self in lyric poetry”); it also provides much-needed space between him and his family (a wife and three-year-old daughter). “We were all on edge,” he writes. “Me, Rei, Nina… I needed to remove myself – from the domestic field of battle, from the world.” But on his arrival, our protagonist’s desire for silence and isolation comes into conflict with the Centre’s research into openness and transparency. As part of their experiment, he is expected to sit at a workstation in an open-plan office where he can be monitored and his every key-stroke tabulated. Struggling to cope with these arrangements, our narrator loses complete faith in his project following a disastrous dinner where one of the fellows, loud-mouthed and opinionated, ridicules his work. Rather than pack up and leave, our narrator wanders the outskirts of Wannsee, where he becomes preoccupied with the life of poet Heinrich Von Kleist, whose gravesite he stumbles across, and holes up in his room at the Centre where he binges on episodes of Blue Lives, an ultra-violent cop show (reminiscent of The Shield) where the hero, while torturing criminals, quotes the little known work of Joseph-Marie, Comte de Maistre. When either fate or coincidence sees our narrator meet Anton, the creator of Blue Lives, at a party in Berlin, he begins to discover how deep the rabbit hole goes.

If we judge a novel based on how it addresses the current moment, then Hari Kunzru seems to have published his last two books out of order. White Tears, released back in 2017, is a ghost story that interrogates America’s historical (and current) exploitation of Black musicians with a message about the systemic racism that resonates with the Black Lives Matter movement and the global protests against police violence. In contrast, Red Pill is a nihilistic novel about the culture wars, white nationalism, and populist Presidents that feels more in keeping with the Charlottesville march, the “Dark Web,” and Pepe the Frog memes. Of course, a book about racism, whenever published, is never anything but relevant. As I write this, social media is aflame about a recent letter published in Harper’s Magazine, co-signed by academics and journalists, attacking the pernicious influence of “cancel culture.” But with the pandemic throwing a spanner in the works of capitalism, and partly muting (or making irrelevant) the voices of leaders who came to power based on a deep distrust of “globalists” and the elite, the questions and concerns that Red Pill considers, that haunt the book’s protagonist, right now don’t feel as pertinent as they did even six months ago.

Having said that, if we push aside the issue of immediacy – less the fault of Kunzru and more a symptom of the disaster movie that is 2020 – Red Pill is hit-and-miss when it comes to examining the West’s abrupt lurch to the far right. Our protagonist has the distinct texture of a straw man: the liberal academic, deeply insecure about his work, but unaware of the world around him or how rapidly it’s changing. A man so insular, so blinkered, that the moment he’s exposed to overt examples of white supremacy and fascism his sense of self breaks apart, abandoning his family on the weakest of pretenses. When he asks his wife, a human rights lawyer, why she believes “humans have special rights,” it’s hard not to roll your eyes. I appreciate that this is partly the point of the novel, that it’s the ivory tower academics who are prone to “red-pilling,” but it does make it hard to care when our protagonist begins his descent into madness. On the flip-side, there are numerous affective, memorable moments in the novel. The Deuter Centre, as a setting for the first two-thirds of the book, is this brilliant, paranoid white space, once the location of a Nazi bunker. For all my reservations about the protagonist, there’s this powerful sequence where he starts following (stalking) a father and his daughter, both refugees. His concern, particularly for the daughter, translates into nearly being arrested by the police on suspicion of being a pedophile. However, the best section of the novel is the climax. It’s not a spoiler to say that the book ends with the election of Donald Trump. Kunzru’s framing of election night (and here I will be careful with what I reveal) is genuinely upsetting, recalling how Ottessa Moshfegh treats 9/11 in her novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

Although the concerns discussed in Red Pill may seem like the least of our problems, it does come out a month before the November 2020 election, and at least here it acts as a reminder of what’s at stake when we eventually move beyond the seemingly endless horizon of the pandemic.

This review and more like it in the September 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.