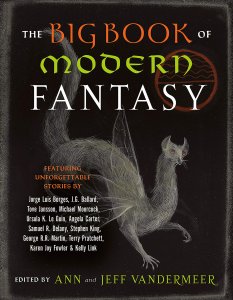

Paul Di Filippo Reviews The Big Book of Modern Fantasy Edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer

The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, Ann & Jeff VanderMeer, eds. (Vintage 978-0525563860, $25, 896pp, trade paperback) July 2020.

The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, Ann & Jeff VanderMeer, eds. (Vintage 978-0525563860, $25, 896pp, trade paperback) July 2020.

When last we saw our intrepid curatorial editors, Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, just a year ago in fact, they were hacking their way resolutely through the jungles of fantastika like Mr. and Mrs. Indiana Jones, emerging with an Ark of the Covenant labeled The Big Book of Classic Fantasy. (You can see my review of that volume here.) Wisely, they capped their explorations at the end of World War II, a pivotal milestone if ever there was one, both for literature and for the world at large. Now comes the companion volume, picking up directly where its predecessor left off: over 800 pages of bliss-inducing non-mimetic goodness which attempts the impossible: to limn the full dimensions of the unreal in today’s literature. Their first selection dates to 1946, and the newest to 2010. This decade gap between the end of the table of contents and the present moment is a wise one, I think, since values of eternality need time to become apparent. As the editors describe the practice in their introduction, it’s “an exclusion zone…important for objectivity.”

That introduction, by the way, hews to the same stimulating and impeccable standards of their earlier pieces, as they lay out their definitions, selection criteria, and goals. But the foreword ends on a sad note, as the VanderMeers announce that they are retiring from producing any more such volumes. Let us be grateful for this last magnificent venture.

It will of course be impossible for me to speak individually about each story in so vast a compendium—ninety-one tales—so I will have to hit the highlights, with an eye towards those stories which perhaps best typify certain different voices, concepts, subgenres, careers, etc. Perhaps dipping into and out of each decade would also be a good tactic.

Maurice Richardson, a UK author who is definitely a cult figure, weighs in with a brilliant surreal jape entitled “Ten Rounds with Grandfather Clock”. This prizefight between man and horologe is the ancestor of Steve Aylett’s gonzo fantasy. Rounding out the first decade is Borges’s “The Zahir”, with its cursed coin that preempts all other thoughts. Seeing Borges’s name on the table of contents is indicative of one way in which this book will differ from its predecessor. The Big Book of Classic Fantasy, with a remit deeper in the past, naturally included more obscure, time-shrouded names, while this volume will necessarily feature a greater number of names more prominent on the twenty-first-century radar.

Moving into the 1950s, we see this principle in action as we enjoy Gabriel García Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings”. Its portrait of an anomalous derelict who hovers between mortal and angel is touching. And we note that even when the editors select a famous name, they dip into the less-well-known stuff.

As the editors say in their intro, they like to break down barriers between “high” art and popular art, so seeing Fritz Leiber consorting with Márquez and Borges is a delight. His “Lean Times in Lankhmar” is a great choice since it shows us his famous companionable heroes, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, separate and at odds.

How better to kick off the 1960s than with Michael Moorcock’s “The Dreaming City”, the debut of Elric of Melniboné. Sixty subsequent years have not staled its lush and droll decadence. Tove Jansson’s “The Last Dragon in the World,” a sweet but not saccharine Moomintroll adventure, illustrates the tenacity of the VanderMeers in going farther afield with their net, and not remaining in easy Anglo-American territory. Lafferty’s “Narrow Valley” brings in the slapstick, tall-tale elements of fantasy which are sometimes slighted in favor of more finely hewn, even “academic” art.

Note that it took a full three decades of fantastika output to fill the first 200 or so pages (we make the transition on page 224, with Rosario Ferré’s “The Youngest Doll”), but that the next decade, the 1970s, will furnish out a whole hundred pages by itself, while the 1980s will flesh out over 150 pages. Finally, the complete latter half of the book is devoted to the 1990s and the Oughties. This bears out the observation made by the editors in their introduction about the burgeoning popularity of fantasy, as it became more commodified and dominant in various non-book media.

But commodification certainly did not eliminate high quality works, as the 1970s prove with such gems as Sylvia Townsend Warner’s “Winged Creatures” (one of her inimitable stories of the fey); the haunting “Linnaeus Forgets” by Fred Chappell (a kind of steampunk take on Sturgeon’s “Microcosmic God”); and Greg Bear’s Bradburyian meditation on the power of storytelling, “The White Horse Child”.

Such powerhouses as George R.R. Martin, Stephen King, and Jane Yolen guide us into the Eighties, but my two favorites here are from smaller stars, and more understated. In “The Luck in the Head”, M. John Harrison charts the adventures of hapless poet Ardwick Crome, who lives in the bedazzling city of Uroconium, showing us MJH’s influence on China Miéville and, ahem, also on a certain J. VanderMeer. And Rachel Pollack gives us a fairy tale engaged with inequality in “The Girl Who Went to the Rich Neighborhood”.

I should insert a mention at this point of the fabulous individual introductions for each author, which are mini-biographies and capsule career critiques.

We greet the 1990s with that decade’s quintessential author, Haruki Murakami, and his “TV People”, a distillation of Murakami’s pitch-perfect encapsulation of modern anomie dotted with surrealism. Carol Emshwiller shines with “Moon Songs”, which actually might be a highly transmogrified and warped version of the Merrie Melodies “One Froggy Evening.” Kelly Link’s twisted fairy tale exegesis, “Travels with the Snow Queen” marks another essential blossom from this era.

The final section devoted to the newest stories is an embarrassment of riches. Several tales from non-English-speaking authors appear here for the first time in their newly minted translations, offering distinctly non-Anglo outlooks. The much-missed Stepan Chapman contributes “State Secrets of Aphasia”, which runs Marx Brothers riffs on several imaginary nations. Jeff Ford’s “The Weight of Words” offers spooky linguistic legerdemain. And Aimee Bender’s “End of the Line” is a tragicomic mediation on power dynamics, featuring a literal manikin that is the pet of a normal-sized human.

Shutting off my spotlight focused on individual works, I feel guilty at all the ones I’ve “slighted,” from Angela Carter to Joe Hill, Le Guin to Ballingrud, McKillip to Rhys Hughes. But rest assured that every item in this book justifies its inclusion.

This does not mean that we cannot still play the game of “who’s been left out.” We could imagine substitutions from de Camp & Pratt, Jonathan Carroll, Avram Davidson, Kit Reed, Tim Powers, James Blaylock, Ramsey Campbell, Robert Holdstock, and on and on. I had expected to see some Theodore Sturgeon, for in fact he is not included in the previous volume nor in the VanderMeers’s other related anthology, The Weird. His omission from all three is a definite gap. But so the editorial scalpel gets employed.

In terms of themes, the Vandermeers definitely prefer stories grounded in our naturalistic world, with Tolkienesque subcreation tales and High Fantasy taking a secondary role. There are very few ghost stories, despite that subgenre’s large presence in the marketplace—ghosts being too much horror-related, perhaps? And aside from Terry Pratchett, represented by “Troll Bridge”, there’s not a lot of outright comedic works. A dash of Tom Holt or Christopher Moore might have added some leavening to a lot of somber excursions.

But these are all the tiniest of quibbles when considering the judicious selectivity, fine taste, and rigorous sense of inclusiveness on display. The VanderMeers might be hanging up their editorial Indiana Jones hats and bullwhips, but they have left a definitive legacy that will be hard to top.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

The link connects to Amazon’s book section, but not the book itself. Amazon can no longer search for books by the ISBN, only by title and author.

Thanks, we’ve corrected it.