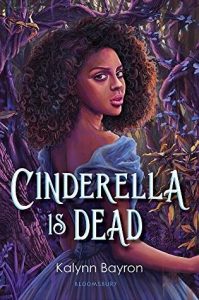

Kalynn Bayron Guest Post–“We Have Always Lived in the Castle: Black Women in Horror”

Black women have always contributed significantly to the horror genre, though our roles have been massively downplayed and overlooked by the larger genre fiction community. As a result, Black women have had to carve out a space and make a way out of no way. Our relationship to trauma, our storytelling culture, our willingness to show that everyday life has the potential to be a horror in and of itself when you exist as a Black woman, puts us in a position to weave tales that conjure the supernatural, the unexplainable, the unthinkable, in ways that no one but us could begin to imagine. And still, when discussing horror the names of Black creators are often unfamiliar. So where have Black women been?

Right here.

The entire time.

My first introduction to the horror genre was The Shining. When I was eleven I bought a copy at a thrift store for a dollar. The lady at the counter said it was the scariest thing she’d ever read and cautioned me against reading it. I ignored her and read it everyday until I was done. It was scary. Horrifying. But I didn’t understand why Danny didn’t just tell his parents that he was seeing ghosts and having visions. For me, coming from a family whose roots stretched right down into the heart of the South no matter how far we’d roamed, a belief in the supernatural is almost a birthright and protections against such specters is commonplace. No mentions of Florida water or laundry bluing, no haint blue awnings, no ancestors. Why didn’t his grandmas or aunties fix him right up? I didn’t understand.

I picked up horror titles anywhere I could, searching for something that felt a little more familiar. When I asked about reading more horror at my local library I was pointed to more Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Anne Rice, and H. P. Lovecraft (insert the viral white man blinking GIF here). Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In the Castle was one of the stories that stuck with me. The tale isn’t particularly gruesome or gory but it got under my skin. I came back to it again and again trying to discover what it was about this story that resonated with me. The profound othering of the Blackwood family had always felt familiar to me as were some of Merricat’s attempts at magic. I realized then that I was looking for something else, not just in the narrative but in the feel of the story itself. I was looking for the author’s voice and I was hoping it sounded like me, like us.

In the summer of 1996, when I was twelve, I called my dad and told him what was going on. He said, “You gotta read books by us if you want to see us.” So, I took a bus to the library and asked if they had any scary books by Black authors. That librarian looked something up, left, and came back with a copy of Toni Morrison’s Beloved. She told me to be careful because the language was “strong” and the themes were maybe more mature than what I was ready for. No such warnings had accompanied any of the other titles I’d checked out that summer. After I read Beloved, I had questions for everyone around me. They’d all steered me towards King, Rice, Poe, Jackson, but why not here? Why not to this story that instilled such a creeping sense of dread and sadness and horrors—true horrors? This was the feeling I was chasing. Morrison’s words were familiar to me in a way that made me feel connected to the lives of her characters and her portrayal of the supernatural. I felt like I was listening in on a story my grandmother might have told. To this day, if I close my eyes, I can recreate the exact feeling I had in the moment I read those first lines: “124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children.” It was amazement, run straight through with a healthy dose of fear.

In the summer of 1996, when I was twelve, I called my dad and told him what was going on. He said, “You gotta read books by us if you want to see us.” So, I took a bus to the library and asked if they had any scary books by Black authors. That librarian looked something up, left, and came back with a copy of Toni Morrison’s Beloved. She told me to be careful because the language was “strong” and the themes were maybe more mature than what I was ready for. No such warnings had accompanied any of the other titles I’d checked out that summer. After I read Beloved, I had questions for everyone around me. They’d all steered me towards King, Rice, Poe, Jackson, but why not here? Why not to this story that instilled such a creeping sense of dread and sadness and horrors—true horrors? This was the feeling I was chasing. Morrison’s words were familiar to me in a way that made me feel connected to the lives of her characters and her portrayal of the supernatural. I felt like I was listening in on a story my grandmother might have told. To this day, if I close my eyes, I can recreate the exact feeling I had in the moment I read those first lines: “124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children.” It was amazement, run straight through with a healthy dose of fear.

Morrison led to Hurston which led to Butler which led to Due which led me to understanding that Black women have always been here putting in the work but have been rendered nearly invisible in the genre of horror. And those warnings about subject matter and strong language weren’t anything but thinly veiled racism. It was an understanding that I brought with me into adulthood and into my pursuit of a career in writing. These works by these phenomenal women and so many others were exceptional. They exceed so many other titles I’d read in their craft, their worldbuilding—so why, then, did I have to go searching? Why weren’t these titles presented to me with as much fervent excitement as the other titles by white authors? Because Black women’s work no matter how stellar, no matter how gripping, is undervalued. Always. The goal posts are constantly being moved just out of our reach. We’re told that if we want to see ourselves in genre fiction that we should write it ourselves and when we do there is magically some other requirement that needs to be met. This isn’t unique to publishing but in publishing it is highlighted in a way that leaves no other interpretation. Our industry is 76% white[1] and the racial biases, both implicit and explicit, held by gatekeepers in this industry has impacted the ability of Black authors writing in genre fiction to reach readers like that version of my younger self who was looking, albeit unknowingly at first, for the familiar comfort of a Black woman’s storytelling. They existed then and they exist now.

We exist.

We create.

Black women have been pushing the boundaries of genre fiction for decades. We have always been here. We come from storytellers and for many in the diaspora, who have been separated from our pasts by oceans and generations of oppression, these stories are the modern continuation of our oral traditions. We know what we’re doing and are often doing it in a way that is devoid of the white gaze. There is a viral clip of Toni Morrison in conversation with Jana Wendt that highlights the assumption that even stories written by and for Black women must, at some point, center whiteness to be viable in the “mainstream.” This is why no one had put a copy of Beloved in my hands before that day in the library, it’s why no one had suggested Kindred, it’s why later on in my life when I asked about Black vampires no one suggested Fledgling. Stories that do not center whiteness become almost invisible in places where whiteness is the default. These works aren’t exceptions to the rule. They are the rule—well written, imaginative, terrifying, and a vital part of the fabric of the horror genre.

It is clear that horror written by Black women has a certain feel, a certain way of coming together that is unique. Our stories most often center Black people, our traditions, our culture, our individual experiences as Black people in a framework of systemic racism and oppression. Our stories don’t lend themselves to the established parameters set for what horror should look like through the white gaze and there is no need for them to do so. As is so often the case, when Black women are refused a seat at the table we build our own. As Dr. Kinitra D. Brooks states in her work Searching for Sycorax: Black Women’s Hauntings of Contemporary Horror “…the folkloric horror framework articulates an aesthetic of black women horror creators.” Within this framework people can learn to see horror through the eyes of Black creators, allowing the work to stand on its own without having to conform to Western horror constructs. As Black women continue to take up the pen as a means of expression and resistance, the wider genre fiction community will have to learn to meet us where we are, confront its own biases, and acknowledge in a real and meaningful way the exceptional work that we have always contributed to horror, sci-fi, and fantasy.

Kalynn Bayron is an author and classically trained vocalist. She grew up in Anchorage, Alaska. When she’s not writing you can find her listening to Ella Fitzgerald on loop, attending the theater, watching scary movies, and spending time with her kids. She currently lives in San Antonio, Texas with her family. Find out more at www.kalynnbayron.com.

[1] Diversity Baseline Study 2019, The Diversity Baseline Survey (DBS 2.0) was created by Lee & Low Books

Excellent article. When I worked with Dr Kinitra Brooks to create (with Dr Susana Morris) the anthology SYCORAX’S DAUGHTERS, a collection of horror fiction and poetry by Black Women (which became a finalist for the HWA Bram Stoker Award in Anthology category), we found so many had written and published in places that weren’t obvious to the horror community. In the end, we have over 30 contributors in the anthology.