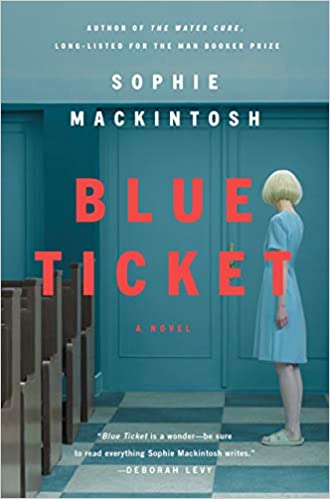

Ian Mond Reviews Blue Ticket by Sophie Mackintosh

Blue Ticket, Sophie Mackintosh (Doubleday 978-0-38554-563-1, $26.95, 304pp, hc) June 2020.

Blue Ticket, Sophie Mackintosh (Doubleday 978-0-38554-563-1, $26.95, 304pp, hc) June 2020.

Sophie Mackintosh’s much anticipated second novel, Blue Ticket, shares several qualities with her critically acclaimed and Man Booker longlisted debut The Water Cure. Both books feature dystopian settings. Both books are deeply concerned with a new wave of reactionary politics – fuelled by right-wing populists and conservative legislative bodies – that look to undermine women’s rights. And both books have intriguing ”what ifs” at their centre. In the case of The Water Cure, it’s what if masculinity was literally toxic? For the Blue Ticket, it’s what if a women’s right to bear children was determined by lottery?

Early on in Blue Ticket, Calla, our first-person protagonist, outlines the horribly simple process that decides a women’s reproductive fate and the trajectory of her life. On the day she experiences her first period, Calla puts on her best dress – because this is a joyous occasion – and heads off with her father to the lottery-station. There she meets other girls around her age, all wearing pretty dresses, all waiting patiently to be summoned. As Calla recalls:

My name was called first. They watched me as I walked the length of the room, towards the machine inside its cloaked box. I put my hand in it. I was apprehensive but ready for my life to be decided…. The machine was silent as it discharged a sliver of hard paper into my hand. It was a deep cobalt.

We learn that there are blue and white tickets. The recipient of a white ticket is compelled to have children, the holder of a blue ticket is forbidden from giving birth. Of course, it’s not framed that way by either the male doctor, who congratulates the blue ticket holders from being ”spared… a terrible benevolence,” or the female physician who implants Calla with a form of contraception – ”she pushed something inside me that hurt, a sharp and spidering pain.” Following the procedure, and having bid farewell to their parents, each girl is handed a bottle of water, a compass, and a sandwich, and told to seek out their destiny. It’s an extraordinarily imaginative and odd set-up, but one that despite Calla’s cool detachment (and even vague sense of nostalgia) feels decidedly wrong and sinister.

The next section of the novel sees Calla living as a blue ticket woman in an unnamed city, in an unknown country, theoretically enjoying her life free of pesky children. However, Calla is not happy. She tells us that for ”weeks there had been a new and dark feeling inside me” a yearning that leads her to acknowledge that while ”there was somewhere I could not go” (i.e. motherhood) she ”wanted to go there.” It’s not much of a spoiler to say that Calla acts on that desire. Having painfully removed the contraceptive device, she finds a man she likes, maybe even loves, and becomes pregnant. When Calla refuses to abort the child, she is forced into exile, given a headstart from an angry mob of women who, if they catch her, have the legal right to kill Calla for betraying her covenant as the recipient of a blue ticket.

The novel again shifts in tone as Calla embarks on a tension-fuelled road trip, through a sketchy world of small towns, dingy hotels, and diners, heading for the border and the promise of freedom. Along the way Calla meets other women (as a side note all the women are given a name, while the men are designated a letter) and it’s during these encounters that Mackintosh raises questions about free will, reproductive rights, and motherhood. There’s a cogent moment where Calla chances upon a white ticket holder fleeing her responsibility to have children. Rather than appreciating that this woman’s right not to have a child is as valid as the right to give birth, Calla is instead overwhelmed by feelings of resentment. It’s an eye-opening moment, that plays into a sadly common mode of thinking that acknowledges a woman’s autonomy over her body but also, in the same breath, views that same woman as selfish if she decides not to have children.

Mackintosh does not attempt to flesh out her world beyond what’s needed to tell Calla’s story. As such, she never explains why this society has resorted to a lottery to regulate birth-rates, or why they need to be controlled in the first place (is it to mitigate overpopulation, is it a radical response to climate change?). I admit that a part of me found this frustrating: I like my dystopias with more flesh on the bone. But I also appreciate that what’s important about the world depicted in Blue Ticket isn’t so much the whys and wherefores, but to recognise that men aren’t required to go through the lottery process to decide who gets sterilised. It’s only ever women who have to struggle, to fight, to flee oppressive regimes, to have any control over their bodies.

This review and more like it in the June 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.