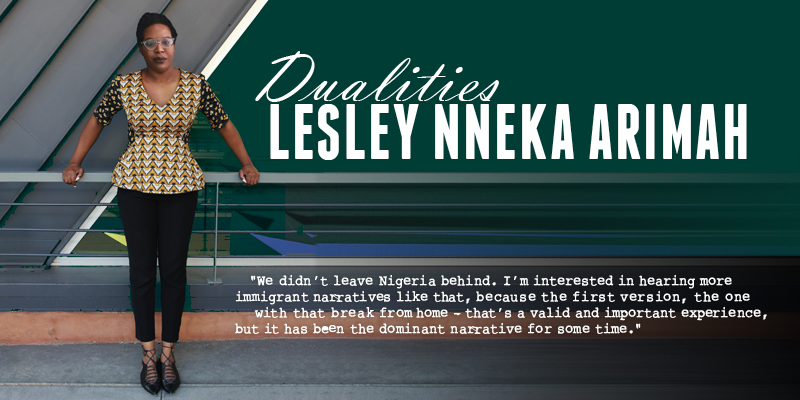

Lesley Nneka Arimah: Dualities

Lesley Nneka Arimah was born October 13, 1983, in London and grew up in Nigeria, Europe, and the US – wherever her father was stationed for work. She attended Florida State University as an undergrad and got her MFA at Minnesota State University, graduating in 2010.

Arimah’s short fiction has appeared in in Granta, Harper’s, McSweeney’s, The New Yorker, A People’s Future of the United States (2019), and several other publications. Her story “Light” (2015) won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize for Africa, “Glory” (2016) won an O. Henry Award, and “Skinned” (2018) won a National Magazine Award and the 2019 Caine Prize in African Writing. The National Book Foundation named her one of “Five Under 35” fiction writers to watch in 2017, and she is a 2019 United States Artists Fellow in Writing.

Her debut collection What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky appeared in 2017 and contains works of literary fiction and SF. It won the Kirkus Prize and the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award. Her first novel is forthcoming.

Arimah lives in Las Vegas.

Excerpts from the interview:

“Moving around a lot as a child was hard – I got used to having a friend for three months and then never seeing them again. I had a hard time socializing and making friends as a teenager because my childhood was spent making a friend for a short while and then leaving before that friendship could deepen or change. I learned to be an observer rather than a participant. Something about moving around and being in a new place very often is that you have to learn how to fit in. Every place has its own rules for how that works, and you learn to observe. I didn’t realize that was preparing me to be a writer, but it did, because I notice things like the power dynamics of a space, and the ingroup/outgroup aspect – it’s just something I automatically catalog. Being a good observer never hurts when writing about the human experience. Also, I can live anywhere for two or three years. Even if it sucks, I can do two years.

“Everywhere we went was very different, but in every one of those places, we were still Nigerian. That was the constant. At one point my dad was working in Algeria, and then Morocco, and then Libya – places that will remind you that you’re Nigerian if you happen to forget. I was probably young enough when we were doing that sort of moving that I didn’t notice what other people’s definitions of being Nigerian were – it was just part of the air I breathed. I think of myself as Nigerian – I jokingly say ‘Nigerian-ish.’ I’m also ‘American-ish,’ in that there’s no denying America is my home for now, nor how much the US has influenced me culturally.

“I have friends and family in Nigeria. My father lives there. It’s not something in the distance or the background. I visit them semi-frequently – I was there for two months last year – and I often consider moving back. It’s funny, because there is a popular immigrant narrative that’s really fraught, where you leave home behind and assimilate, and there’s a break between parents and children, where the parents are culturally of one place and the children are culturally of another. I’m not going to say that that didn’t happen – my siblings and I moved to the States when we were teenagers, and of course it had an influence on us culturally – but we didn’t leave Nigeria behind. I’m interested in hearing more immigrant narratives like that, because the first version, the one with that break from home – that’s a valid and important experience, but it has been the dominant narrative for some time. There’s less about the immigrant who comfortably straddles both sides.

“When I was pretty young, my sister and I went to a convent boarding school, and it was not a lot of fun. We both turned to books for comfort. That’s how I ruined my eyes. I would stay up at night trying to read by moonlight because I didn’t want to go to sleep. Books have always been a comfort and a refuge for me, and being a kid and growing up in a place where sometimes electricity isn’t consistent, you learn to entertain yourself. And as I got older, books became a huge part of entertaining myself. My parents were all about education, so they were happy that my sister and I had an interest in reading, because for them it was almost synonymous with studying. It did get to the point where, when I was a teenager, my dad kicked my sister and me outside – ‘All you guys do is read – go get some air, child.’ When we first moved to the States, my sister and I would go to our public library with my dad’s duffel bags and check out the maximum number of books, which was 50. I would read my duffel bag, my 50, and she would read her 50, and then we would swap duffel bags. Then we’d return them to the library and do it all over again.

“I had some writing excursions when I was young. The first thing I remember writing was a retelling of ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarves’, where the seven dwarves were giants. I thought I was being very clever. I was nine or ten. Then when we were in the States, when I was 14 or 15, we got something in the mail – you know those art scam things that say, ‘If you can draw this, you can be Michelangelo!’, or whatever. There was one for writing, too, like an ‘institute for creative writing.’ I wanted to do it. There were 14 or 15 sessions, and I did three or four. You basically wrote something based off a prompt and you sent it off to somebody who graded it, and sent you feedback. I got some negative feedback and I thought, ‘Oh, I’m done with this. I poured my heart and soul into this!’ I know now that the story I wrote was ridiculous, but teenage-me was outraged.

“Those were my minor, early excursions into writing. As for actually seriously writing – when I went to college, I planned on being a lawyer. I was majoring in English and psychology, and in my last semester at Florida State University, I took a workshop with Julianna Baggott, who is a genius. That experience changed everything. I found out about MFA programs. I never really thought through how books came into the world – they were just there for me to read and enjoy. The idea that I could study books, words, and storytelling, and then write my own, and that it could be a career, not a hobby – it was over for me at that point. As soon as I realized that was a thing I could do, that was the only thing I wanted to do with my life.

“The most valuable thing an MFA gives you is time. Don’t pay for one – it’s not worth going into debt for. But it gives you time, and, applied correctly, that time can help you figure out a lot of things. It’s not all good, though. I remember I brought a story in for workshop and got the drafts back, and someone had very kindly gone through my piece and ‘corrected’ the dialogue, because, she said, ‘Africans don’t talk in polysyllabic language like this.’ I was like, ‘A, fuck you, and B, I’m African, and they do, clearly, because I wrote it.’ It can be a challenging environment, creatively. You have to decide how to handle that in the moment. You don’t have to fight every battle you encounter; you’re going to wear yourself out. Take care of you. If you’re going to feel better confronting it and calling it out, then do it; if you are going to feel better silently fuming and then venting to your friends when you get home, do that. It’s not your job to fix these people. Your job is you. Your job is your art. Whichever reaction gives you the most peace and prioritizes your art is what you should do.

“It wasn’t until I was in a workshop situation where nobody cared about the exoticness of my content that I really learned about craft. That was at VONA – the Voices of Our Nations Art Foundation workshop. I’ve done other workshops, but VONA was the one that was the most impactful. Our workshop leader was an amazing educator who gave us the tools to do what we didn’t even know we were trying to do. It was really intense, and an experience that changed the way I thought about teaching and how to run a class. I was exactly where I needed to be for that workshop to have the right impact. It changed things.

“At some point you find your tribe. You find the people who know how to read your work, and who understand what you’re trying to do. They may be exactly of your demographic, or they may not be. Being in a writing community is helpful to finding that tribe, because you meet people and filter through and find the ones who are the right advisers for you and your work. I found that community in Minneapolis. I did this thing called the Loft Mentor Series run by the Loft Literary Center, an organization that plays a significant role in Minneapolis’ literary ecosystem. Every year they pick 12 writers – four non-fiction, four poetry, four fiction – and pair them with a local mentor for a year, and a national mentor who comes in once a year and works with the group. It was a fantastic experience. All of the fiction folks in my year decided to continue meeting as a writing group afterwards – we even poached one of the non-fiction writers – and we were in a writing group for three-and-a-half years, meeting every six to eight weeks. I found my readers, and found my tribe. One woman in particular, Jennifer Bowen Hicks, is quite literally one of the best readers whom I have ever worked with or encountered. Find your people. Find the people who understand, respect, and will give you good feedback for your work. Then hold each other accountable.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Arley Sorg.

Read the full interview in the August 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.