Stefan Dziemianowicz Reviews Astounding by Alec Nevala-Lee

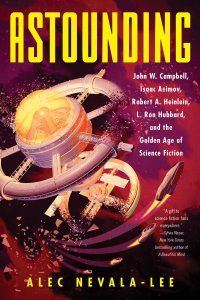

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Alec Nevala-Lee (Dey Street Books, 978-0-06-257194-6, 528pp, $28.99, hc) October 2018.

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Alec Nevala-Lee (Dey Street Books, 978-0-06-257194-6, 528pp, $28.99, hc) October 2018.

The old joke has it that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is… 12 (i.e., the age at which most fans begin reading it). After reading Alec Nevala-Lee›s Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, you might well believe that it’s actually 27. That’s the age at which John W. Campbell inherited the editorship of Astounding Stories, soon to be rechristened Astounding Science-Fiction. The name change was the first imprint Campbell made on the magazine but it was far from his last. As any reader of Locus knows, Astounding was the tool that Campbell used to terraform the landscape of science fiction, nudging it along the evolutionary path from space opera and the super-science fiction that he himself had made his reputation from as a writer to a more sophisticated literature of ideas – or, as Nevala-Lee puts it, “he turned science fiction from a literature of escapism into a machine for generating analogies.”

Although the scope of Nevala-Lee’s study is broad enough to encompass the development of science fiction during the pulp era – both in Astounding and in the magazines that either tried to follow Astounding‘s lead or distinguish their contents from its – his book is primarily a biography of Campbell. It succeeds admirably in tracing the deflection of Campbell’s frustrated ambition to become a scientist into his embrace of the role of science fiction writer and his approach to it as a sort of literary war game in which he could move his hero scientists and inventors around on a playing field the size of innumerable galaxies. Campbell’s success as a writer of science fiction led inevitably to his being tapped to edit it. He had been writing a more thoughtful and reflective type of science fiction for three years under his Don A. Stuart pseudonym when he was offered the gig at Astounding. He was clearly self-confident enough to believe that as an editor he could get other writers to follow suit and shape the fiction to his standards. “We were extensions of himself,” Isaac Asimov is quoted as saying about the writers Campbell published; “we were his literary clones; each of us doing, in his or her own way, things Campbell felt needed doing; things that he could do, but not quite the way that we could.”

Nevala-Lee has subtitled his book “John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction” because the other writers named were important focuses for Campbell’s editorial activities and their careers provide a vantage point from which to view Campbell’s rise and fall as the helmsman of the era’s most important science fiction market. Asimov, who long considered Campbell his mentor, was the apt pupil with whom Campbell could discuss ideas – famously the plot of the story “Nightfall”, the Three Laws of Robotics distilled from Asimov’s earliest robot tales, and the psychohistory of the Foundation saga – that then became stories. Heinlein was the writer who most closely shared Campbell’s vision for what science fiction could achieve, especially post-Campbell, when he began reaching a mainstream readership through his juveniles and sales to Saturday Evening Post and other slick magazines (although Heinlein bristled in his later years at the suggestion that Campbell had shaped his work the way that he had the work of other writers). Hubbard was an enormously popular writer in Astounding during its golden age years, of course, but his impact on Campbell is best gauged by Campbell’s advocacy of dianetics, which was introduced to the world in the pages of Astounding, and his subsequent enthusiasm for pseudosciences that caused writers to distance themselves increasingly from him and his magazine throughout the ’50s.

Campbell’s drift toward the fringe began, as Nevala-Lee shows, as early as the early 1940s, shortly after America’s entry into WWII. A number of Campbell’s core writers volunteered for war duty, among them Heinlein, who urged Campbell to step away from his magazine and do the same. Campbell, however, saw his work at Astounding as doing just that: “[H]e believed that science fiction still had a role to play in the war. It was a laboratory in which his writers could work out scenarios for the future.” Very soon Campbell could say that they had. The March 1944 issue of Astounding carried Cleve Cartmill’s “Deadline”, a story that built on some of Campbell’s speculations in his editorials on the harnessing of nuclear energy. Cartmill’s now notorious atom bomb story sent federal agents scurrying to Campbell’s offices to stanch what they feared was a leak from the Manhattan project more than a year before the dropping of the atomic bomb. The response vindicated Campbell’s conviction that science fiction could serve as a real-life Analytical Laboratory for extrapolating applications of technology to society. “I’ve got the neatest little research organization for high-power thinking anyone ever dreamed up,” Campbell wrote to his father in 1953: “the science fiction readers and authors.”

Enter dianetics. Campbell subscribed to Hubbard’s self-help “science” as one that was destined to supplant clinical psychiatry. Better yet, it had been conjured by one of his own writers who, it could be divined in retrospect, had been working out its particulars in stories that had appeared in the magazine. Campbell’s ardent prosletyzing for dianetics is part of the reason why many of its first adherents – Campbell among them – were science fiction writers and fans. Nevala-Lee gives a compact but comprehensive history of the meteoric success of dianetics and the mismanagement that led to the spectacular collapse of its research foundations in only a year and turned Hubbard into a fugitive for much of the next three decades. Campbell himself retained his belief in dianetics, even though he split with its professional institutions – and it seemed to embolden his drive to champion other dubious sciences and inventions as the next scientific breakthroughs that could be legitimized through his magazine. Nevala-Lee’s coverage of Campbell’s embrace of psionics, the Dean drive, and other farfetched gimmicks is clear-eyed and sympathetic, but also painful to read, in part because it shows Campbell grasping at straws that he would have criticized his writers for a decade earlier, had they done the same in stories that they were submitting to his scientifically grounded magazine. In his final years as the editor of Analog, the new name given Astounding in 1960, Campbell was finding it hard to cultivate and mold new writers as he had done decades earlier, and he had alienated many of the stalwarts who had made their reputations under his tutelage. It evidently embittered him that he could no longer persuade or cajole writers to see things his way, as he had only a little more than a decade before. When, in 1967, Campbell asked Robert Silverberg, a Campbell admirer early in his career, why he and other well-known writers were no longer submitting to him, Silverberg replied honestly, “I’m no longer comfortable with your thoughts.”

Some of the stories and anecdotes in Astounding will be familiar to readers who have read Isaac Asimov’s and Fredrick Pohl’s autobiographies, as well as non-fiction studies of the genre and its fandom by Sam Moskowitz, Damon Knight, Lester del Rey, and other chroniclers. Many won’t be, though. Nevala-Lee has mined letters, interviews, memoirs, and even recordings of convention panel discussions for the data he’s assembled for his narrative, some of it previously unpublished and much of it hitherto inaccessible to all but the most diehard devotees of its subject. More important is the context he provides for it. More than a biography, his book is a recreation of the dawn of modern science fiction and the lives of writers who made their greatest impact on it. It gives the reader a fully realized sense, not only of the times and the issues shaping the development of science fiction and the dynamic between the fiction and its fandom, but also what it was like for a writer to visit Campbell at his Street & Smith editorial offices, or to socialize with other writers at conventions and family get-togethers, or to engage in bull sessions and debates on the hot topics of the day. Astounding is an excellent contribution to science fiction studies that deserves to sit on the shelf along with the memoirs and histories written by those who lived through the era it covers and who themselves made their mark on it.

Stefan Dziemianowicz, Contributing Editor, is author of The Annotated Guide to Unknown and Unknown Worlds and a collection of re-told urban legends, Bloody Mary and Other Tales for a Dark Night, and editor (with S.T. Joshi) of three-volume reference work Supernatural Literature of the World: An Encyclopedia and of more than thirty anthologies including Bram Stoker Award-winning Horrors: 365 Scary Stories, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, and 100 Ghastly Little Ghost Stories. Between 1991 and 1999, he edited critical magazine Necrofile: The Review of Horror Fiction. His critical work on horror and fantasy fiction has appeared in Washington Post Book World, Lovecraft Studies, and other publications, and he is a regular contributor to Publishers Weekly.

This review and more like it in the December 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

This is a very interesting book, which gave me some surprises.

1) That Heinlein had been that hoodwinked by Hubbard during WWII , seemingly because Hubbard was able to serve active duty. I guess Heinlein never knew how many times Hubbard was relieved of duty and finally given a desk job? Heinlein , sort of, introduced Hubbard to Jack Parsons , which became a mind blowing story in itself. Oddly it was Hubbard’s dealings with Parson’s that finally put Hubbard in Heinlein’s dog house!

2) I knew Hubbard was entwined with Campbell in the late 40s, but I did not know the extent to which he and Hubbard worked on Dianetics together just before it was published. I did not know Campbell had worked at a Hubbard ‘Dianetics Clinic’ in New Jersey seemingly thinking he would take that up and leave editing.

3) One thing about Campbell that had influence on me, Nevala-Lee mentions it in one instance in the book, his eye for art. I was pulled into science fiction because of the ‘domesticated super science’ , the lived-in fell, the verisimilitude …. I am guessing that Campbell had an eye for it’s realization in art? The Rogers covers in the 40’s may be ‘muddy’ but they are evocative. In the 1950s Kelly Freas and Ed Emshwiller just nailed it. Not only the cover art but the interiors also…. Those black and white illustrations were a realization of the milieu of the best writers in ASF. (I think EMSH gets a little short changed on this, he did great realizations on the cover now and then, but his interior work was better than Freas, and Freas did great interior work.) There were other artists too, who did good work. Campbell’s eye was the best. Campbell should get credit for this.