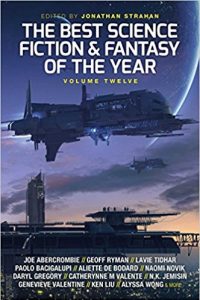

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year: Volume 12, edited Jonathan Strahan

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year: Volume 12, Jonathan Strahan, ed. (Solaris 978-1781085738, $19.99, 620pp, tp) April 2018. Cover by Adam Tredowski.

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year: Volume 12, Jonathan Strahan, ed. (Solaris 978-1781085738, $19.99, 620pp, tp) April 2018. Cover by Adam Tredowski.

After many years – sometimes it feels like too many – of reading year’s best anthologies, I’ve come to the conclusion that they serve three different purposes for three different but overlapping audiences. The first, and most obvious, is to provide a rich and entertaining variety of stories for the general literary reader; we might quibble over why a particular story was considered “best,” or why a favored story didn’t make it, but, given the considerable variety of talent at work these days, it would take a Trumpian level of incompetence to produce an annual that wasn’t, on the whole, pretty readable – and Strahan (a colleague on this magazine and our podcast) has the advantage of eclectic tastes, both stylistically and thematically. The second purpose is that they provide a useful service for those of us who at least nominally try to keep up with the field, helping to identify trends, letting us know what old favorites are up to, and, perhaps more importantly, introducing us to newer writers who might emerge as major figures over the next few years. The third purpose might be to serve as an introduction to the field for readers thinking it may be time to catch up on this sci-fi stuff, or as a reintroduction for those who may have drifted away years earlier. I have no idea what proportion of the market this latter group might represent (not a lot, I suspect), but an interested novice faced with a daunting bookstore section or Amazon algorithm full of widely varied and unfamiliar titles might reasonably expect that something called the Year’s Best is a good place to dive back in.

Jonathan Strahan’s introduction to his twelfth annual volume – which puts him on a par with Judith Merril, whose pioneering series ended with its twelfth volume in 1968, but still far short of Gardner Dozois’s unequalled run – mostly addresses that middle group of self-identified SF readers, likely the core market. But I wonder what each of these audiences might take away from the stories here, which range from the solidly hard SF of Tobias S. Buckell, Yoon Ha Lee, and Linda Nagata, to historical fantasies from Mary Robinette Kowal and Theodora Goss, to unnervingly timely stories from Karl Schroeder, Nick Wolven, Greg Egan, Kai Ashante Wilson, Dave Hutchison, and Charlie Jane Anders. More than in most Strahan annuals, these latter tales sometimes tilt toward horror, not a formal remit of Strahan’s selection process, but perhaps an indication of where writers’ imaginations are leading them these days.

But back to those hypothetical readers. The lead story, Tobias S. Buckell’s “Zen and the Art of Starship Maintenance”, should delight veteran SF readers with its spectacular setting near a black hole, its waggish names for spaceships (a trend apparently started by Iain M. Banks but now picked up by everyone), and its sardonic narrator, a maintenance robot compelled by its Asimovian directives to serve a rather weaselly human CEO. The general reader less interested in hardware and black holes might see it as a clever tale in the old tradition of the slave outwitting its master, while the former SF reader now all grown up might be pleased to see that versions of Asimov’s laws are still among the tools of the trade. Some of the same themes are echoed later with Suzanne Palmer’s “The Secret Life of Bots”. (Another odd, but probably minor trend seems to be borrowing bits of titles – Buckell from Robert Pirsig’s old memoir, Palmer from the Sue Monk novel, Max Gladstone’s “Crispin’s Model” from Lovecraft, Egan’s “The Discrete Charm of the Turing Machine” from Bunuel, Kai Ashante Wilson’s “The Lamentation of Their Women” from Conan the Barbarian, of all places.)

The general point is that, depending on what you’re reading for, the stories fall into some very different kinds of groupings. The SF reader will find a natural link between the Buckell story and other space-opera-like tales such as Yoon Ha Lee’s delightful “The Chameleon’s Gloves”, in which an art thief is assigned to track down a rogue general with a doomsday weapon, or Alastair Reynold’s haunting far-future tale of thousand-year galactic reunions, “Belladonna Nights”, with its very effective narrative twist. On the fantasy side of the ledger, another clever thief deals with squabbling royal heirs in Daniel Abraham’s “The Mocking Tower”. But the outwitting-those-in-power theme of Buckell can also link it to Vina Jie-Min Prasad’s much more mundane but still satisfying “A Series of Steaks”, in which a forger of steaks (using a bioprinter) outwits a powerful merchant who threatens her. “Belladonna Nights”, on the other hand, with its future-as-past narrative angle (a technique perfected decades ago by Cordwainer Smith), might link it to similarly elegiac narratives of the nearer future, such as Linda Nagata’s tale of an artist on a dying Earth striving to finish her final work – an obelisk on Mars, remotely constructed by robots – or Indrapramit Das’s “The Moon is Not a Battlefield”, in which a combat veteran recalls a lunar war involving an Indian colony there.

Another possible grouping of stories offers SFnal treatments of very current issues – bioprinting food in the Prasad story, cryptocurrencies in Karl Schroeder’s “Eminence”, which combines economic satire with the role of social capital or “eminence” – which also becomes a central topic in Nick Wolven’s “Confessions of a Con Girl”, perhaps the most inventive narration here, in the form of a student’s pre-college senior thesis essay. Schroeder’s account of the financial impact of a homegrown “potlatch” cryptocurrency is not only entertaining, but explains the whole concept more succinctly than most economists have been able to. Greg Egan’s “The Discrete Charm of the Turing Machine” – like much of his short fiction, more accessible and less arcane than his recent novels – begins by making a disturbingly convincing case that an AI might replace you at work by simply observing and then cloning your skills, but eventually turns into a kind of consumerist satire reminiscent of early Frederik Pohl. Issues of racism and power are confronted in Kai Ashante Wilson’s “The Lamentation of Their Women”, one of the liveliest but most violent fantasies here, edging into horror, and in Dave Hutchison’s more restrained but more bluntly didactic “Babylon”, about a Somali spy’s radical tactic for infiltration and assimilation.

Perhaps the most chilling single story here, though, and one of the highlights of the volume, is Charlie Jane Anders’s “Don’t Press Charges and I Won’t Sue”, another horror tale about an Orwellian program called Love and Dignity for Everyone, which sets out to “cure” transgender people like Rachel by forcibly downloading their identities into cadavers with socially approved gender assignments. The dystopian elements are underscored by Rachel’s memories of her earlier life with her childhood friend Jeff – who is witnessing her transformation – and by a creepy narrative voice that reminds us that before we feel too sorry for her, we should remember that she “holds a great many controversial views” – as though that alone is an indictment worthy of disembodiment. Almost equally chilling, if only because of its pointed connections to contemporary life, is Samuel R. Delany’s first science fiction story in years, “The Hermit of Houston”, which traces the relationship of the narrator and his lover Cellibrex in a 22nd century in which national borders have dissolved, Facebook is remembered as “the greatest of the old religions,” and “the election of 2020 was the Trump of Doom for the Pence.” Although gender-switching has become common, it becomes apparent that gay people and women have borne the brunt of population control in this decomposing society.

The gloomy prospects set forth by the Anders and Delany stories might lead some readers to seek respite in the fantasy selections, and indeed Scott Lynch’s headlong tale of a search for dragon gold, “The Smoke of Gold is Glory”, offers many familiar rewards of a comic fantasy quest, even if it doesn’t do much new conceptually. But even in some of the best fantasy selections there is a sense of lost worlds and lost opportunities. In Kelly Barnhill’s touching “Probably Still the Chosen One”, a girl waits her entire life for the return of a “High Priest” of fairyland who visited her once as a child, while Caroline M. Yoachim’s “Carnival Nine” seems to take us into a playful kidlit world of living windup toys, until it evolves into a kind of family tragedy. The two stories set largely in Victorian England hardly present that world as a nostalgic respite, either: Mary Robinette Kowal’s “The Worshipful Society of Glovers” is a Dickensian class melodrama of an apprentice glovemaker trying to save his ill sister with the aid of brownies, while Theodora Goss’s “Come See the Living Dryad” is less a fantasy than a century-old murder mystery involving a disfiguring form of dysplasia, exploitative freakshows, and a modern woman trying to trace her identity. Both are beautifully written, but offer little consolation.

As usual, Strahan has scoured an impressive variety of sources for these 29 stories. The reader returning to SF after some time away will recognize familiar old venues such as F&SF, Asimov’s, and even the resurrected Omni (the source of Maureen McHugh’s affecting, Twilight Zone-ish “Sidewalks”), while the current SF reader won’t be surprised to see stories from Tor.com, Clarkesworld, or Lightspeed. Only a true devotee would have been able to find the stories from Boston Review (a special issue on “global dystopias,” in which the Charlie Jane Anders tale was by far the best), or from anthologies like The Djinn Falls in Love (Said Z. Hossain’s “Bring Your Own Spoon”, perhaps the only postapocalyptic djinn restaurant story you’ll ever read), or even the author’s own subscriber mailing list (Caitlín R. Kiernan’s magical realist “Fairy Tale of Wood Street”). Of the making of short fiction there is no end, and apparently no end of places to publish it, either, so as always it’s good to have a trusted and indefatigable gleaner on our side.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the April 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.