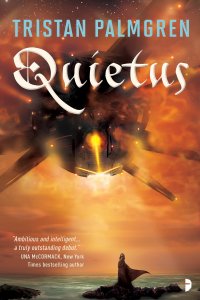

Paul Di Filippo reviews Quietus by Tristan Palmgren

Quietus, by Tristan Palmgren (Angry Robot 978-0857667434, $12.99, 464pp, trade paperback) March 2018

Hidden spies from a high-tech culture inserted into the primitive polity of fellow humans in order to gather data, while obedient to a clause not to interfere. Oh, we must be talking about one of Connie Willis’s time-travel novels, or perhaps an installment of Kage Baker’s Company franchise. Maybe even The Man Who Fell to Earth. But–surprise!–we are not. Instead we are looking at the debut novel from Tristan Palmgren, a book that might share a few conceptual elements employed by Willis and Baker (and others, extending back at least as far as Leiber’s Change War tales) but which nonetheless stands out as very distinctive and different and highly accomplished. This promising launch of Palmgren’s career should be heralded widely.

Hidden spies from a high-tech culture inserted into the primitive polity of fellow humans in order to gather data, while obedient to a clause not to interfere. Oh, we must be talking about one of Connie Willis’s time-travel novels, or perhaps an installment of Kage Baker’s Company franchise. Maybe even The Man Who Fell to Earth. But–surprise!–we are not. Instead we are looking at the debut novel from Tristan Palmgren, a book that might share a few conceptual elements employed by Willis and Baker (and others, extending back at least as far as Leiber’s Change War tales) but which nonetheless stands out as very distinctive and different and highly accomplished. This promising launch of Palmgren’s career should be heralded widely.

Here’s the basic setup. There is a vast organization dubbed the Unity. It extends not up and down a single timeline, but across the multiverse, taking in millions of “planes.” (And here we detect echoes from all those great multiversal sagas such as Keith Laumer’s Worlds of the Imperium and, more recently, Ian McDonald’s Everness series and the Baxter and Pratchett Long Earth saga.) The Unity is run by “amalgamates,” the only unfettered artificial intelligences around. Other AIs are “neutered” to lesser capacities: NAIs. Humans, while far from the only sentient species in this crosstime vastness, are a favored partner and tool of the amalgamates. The whole empire has been fine-tuned–“The amalgamates had conquered threats before… Other trans-planar empires. World-eater AIs. Memetic parasites. Plane-leaping vacuum metastability events.”–and is running swell. Or it would be if not for the advent of the oneirophage, a kind of brain-eating metaphysical ailment which even the amalgamates cannot handle.

Looking to understand the societal protocols of past plagues as a kind of anti-panic measure, the Unity has sent a mission to one version of Earth that is still living out the infamous medieval Black Plague. The mission consists of five individuals. Habidah, our main viewpoint character; Feliks, Joao, Kacienta and Meloku (also given her own intermittent chapters of narration). Disguised as typical citizens of the 1400s, operating from a subterranean base, they circulate among the unsuspecting natives, mostly in Italy. And during her pursuit of knowledge, Habidah will encounter a youngish monk named Niccolucio. Finding him on the point of death, she violates her mandate and brings him back to the base. Healing him, she also shares some of the realities of the Unity with him, then sends him off to Florence to help in the program of collecting data. She even gets retroactive approval from her superiors back in the Unity.

But then, everything goes kerflooey. A vast interstellar warship, the Ways and Means, hosting one of the amalgamates onboard, transits over to this plane for reasons unknown, manifesting in orbit around Earth. Suddenly the spies are involved in much larger and consequential doings, and Niccolucio proves to be a much more potent player than ever suspected.

Palmgren’s virtues as a writer are evident from page one. First off, he creates a cast of utterly rounded characters, Habidah first and foremost. Her reluctance ever to return to her home is just one of the engaging tidbits about her. These ultra-sophisticated, nearly posthuman Unity folks (they are laced with “demiorganic” implants and ridealong NAIs) are the endpoint essences of thousands of years of culture. (The Unity has been around for fifteen millennia.) Yet their motives and emotions remain relatable. Niccolucio and his fellow natives exhibit a completely believable mentality for this historical 1400s as we know that era. And when you put the two types together, the cognitive dissonance is enchanting.

As for the rich setting: not to spoil anything, I hope, but I can say that over eighty percent of the book takes place on the planet, and thus we are almost reading a historical novel insofar as Palmgren seeks to recreates this period. And indeed, he succeeds with gusto. From the misery and stinks to the faith and art, he conjures up a vivid representation. (A subplot involving the Avignon papacy and Meloku is intriguing.) When the book does shift to a more high-tech venue, the author unleashes a gosh-wow torrent of van-Vogtian superscience and enigmatic strategies. This is the kind of pure quill stefnal pyrotechnics which John C. Wright–no matter what you think of his politics–nailed so precisely and in twenty-first-century fashion.

The battle had taken place in a flash of milliseconds, before she realized it had started. The amalgamate had cut power to this chamber, an emergency attempt to stem the tide of data flowing out of Nicclucio’s mind.

And Palmgren doesn’t play for small stakes either. The book’s climax kicks the game board to the floor–in preparation, one presumes, for volume two of the series, Terminus, which we are teased with at the close of the novel.

Tristan Palmgren’s first book proves that no SF “power chord” is ever fully exploited, so long as visionary new writers keep popping up in the multiverse.