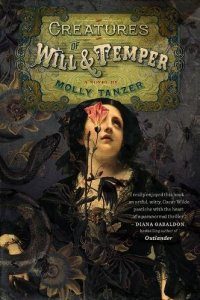

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Creatures of Will and Temper by Molly Tanzer

Creatures of Will and Temper, Molly Tanzer (Houghton Mifflin Mariner 978-1-328-71026-0, $16.99, 346pp, tp) November 2017.

Creatures of Will and Temper, Molly Tanzer (Houghton Mifflin Mariner 978-1-328-71026-0, $16.99, 346pp, tp) November 2017.

Something often overlooked in this whole business of setting fiction in the Victorian era, whether steampunk or its various fantasy and horror offshoots, is that the Victorians were perfectly capable of writing their own fantasy, SF, and horror, some of it classic. This may be one reason I have less sympathy for novels and stories that purport to inject a note of the fantastic into a culture perceived as hopelessly stodgy and mired in gloomy realism, and more for stories that recognize the actual richness of the Victorian imagination. Tim Powers has long done this by incorporating historical figures from Shelley and Byron to the Rossettis in his novels, and Theodora Goss seemed to be making a point of it with The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter (reviewed here in June), with characters derived from specific works by Shelley, Stevenson, Wells, Stoker, and Hawthorne (the lone American in the mix, though much of what I’m saying holds as true for American 19th century lit). I’m not talking here about the endless variations on Dracula and Frankenstein (which wasn’t a Victorian novel anyway, to be nitpicky), most of which are drawn more from wildly careening pop mythology than from the actual source texts, but rather works which actively engage with and interrogate their sources, and which invite us to do the same.

Molly Tanzer’s Creatures of Will and Temper belongs to this latter group. It directly engages Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, which surprisingly hasn’t been as widely treated in later fantasy as you might suspect (though Dorian did show up in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and the whack-a-mole game of Victorian monsters in John Logan’s Penny Dreadful TV series a couple of years ago). Although it’s not necessary to have read Wilde in order to enjoy Tanzer’s well-researched novel, which eventually turns Wilde’s moral fable into a more familiar contest of demons, those who have will immediately recognize the painter Basil Hallwell – who painted the original portrait – and the decadent Lord Henry Wotton, here gender-shifted into Lady Henrietta Wotton, even though everyone still calls her Henry. Dorian himself is transformed into Hallwell’s niece Dorina Gray, a provincial teenager with ambitions of becoming an art critic (a sign of incipient decadence if there ever was one). Most of the other characters are of Tanzer’s own invention, as are the main outlines of the plot.

And that plot divides neatly, if rather abruptly, into two parts. In the first, Dorina and her less glamorous sister Evadne, who has just had her heart broken by her only male friend and longtime fencing partner, prepare to travel to London to stay with their uncle Basil, who is still in mourning over the death of his lover, Lady Henry’s brother, whose portrait he has just completed. Dorina, who is gay, is eager to visit museums and perhaps to find a more interesting range of lovers, while Evadne’s role is primarily that of chaperone. Not surprisingly, Dorina immediately hits it off with Lady Henry, while Evadne, left largely to her own devices, finds herself involved with an elite fencing academy, where she quickly becomes the star pupil. The testy relationship between the sisters is beautifully handled, as are the settings, and the first half of the novel is largely a domestic family drama, which hardly need any supernatural intimations at all – which is just as well, since it doesn’t get any.

Needless to say, both Lady Henry and her circle and the fencing academy are more than they at first seem. Dorina enthusiastically takes to the art world that Henry introduces her to, and Tanzer cleverly uses their discussions of actual National Gallery paintings by Titian and Rubens to underline not only aspects of character, but the central role that art comes to play in the narrative. Meanwhile, Evadne, always the wallflower to her more glamorous younger sister, finds a new role for herself, and even the possibility of romance, as she becomes the unexpected star of the fencing academy. Tanzer ingeniously manages the shifting loyalties as the novel segues rather quickly into thriller mode, and keeps the question of exactly who the good guys and the bad guys are open almost until her rather improbably fast-moving conclusion, in which Evadne, easily the most compelling of the original characters, more or less discovers her inner Jackie Chan. There are some interesting notions about the world of demons and how they seem to function almost like addictive performance-enhancing drugs, and along the way Tanzer manages to suggest how her demonology might even account for the central conceit of Wilde’s original novel. There are moments when her characters sound a bit too contemporary, tossing about terms like “paranormal” and “lifestyle,” but for the most part her version of Victorian London is deeply textured and evocative, and her characters treated with convincing complexity.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the December 2017 issue of Locus.