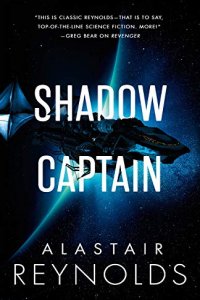

Stefan Dziemianowicz reviews Haunted Nights by Ellen Datlow & Lisa Morton, eds.

Haunted Nights, Ellen Datlow & Lisa Morton, eds. (Blumhouse/Anchor 978-1-101-97383-7, $16.95, 368pp, tp) October 2017.

In the horror field it’s pretty much a given that every writer has at least one good Halloween story up his or her sleeve. Haunted Nights, edited by Ellen Datlow & Lisa Morton under the auspices of the Horror Writers Association, is an anthology of 16 previously unpublished stories on the Halloween theme that bears this out. The stories offer a wide variety of approaches to Halloween and all its trimmings, and several are arguably among the strongest work that their authors have produced and are likely contenders for consideration for year’s-best roundups.

In the horror field it’s pretty much a given that every writer has at least one good Halloween story up his or her sleeve. Haunted Nights, edited by Ellen Datlow & Lisa Morton under the auspices of the Horror Writers Association, is an anthology of 16 previously unpublished stories on the Halloween theme that bears this out. The stories offer a wide variety of approaches to Halloween and all its trimmings, and several are arguably among the strongest work that their authors have produced and are likely contenders for consideration for year’s-best roundups.

The majority of stories offer imaginative riffs on Halloween lore and traditions. There are two tales on the origin of the jack-o-lantern, based on the western European legend of Jack-o’-the lantern, a man who tricked the devil out of taking his soul and who, upon his death, was cursed to wander eternity carrying a candlelit turnip to light his way. In Joanna Parypinki’s “Wick’s End”, Jack is a wily modern serial killer who lures new victims to their death each Halloween so that he can steal “the burning flame of a human soul” to keep his lantern lit. In Pat Cadigan’s “Jack”, the eponymous character is a Wandering Jew-type figure who tries to trick the souls of the newly dead to exchange places with him. Cadigan’s tale is especially fun because of its narrator, a jaded occult sensitive who has thwarted Jack’s mischief on more than one occasion and who speaks in the world-weary voice of someone familiar with all of his subterfuges. Kelley Armstrong’s “Nos Galen Gaeaf” is, as its title suggests, a story steeped in Welsh legendry – in this case, the tradition of an entire town placing stones with the names of its people written on them around a Halloween bonfire to determine who among them will die within the year. Armstrong has adapted this lore to her contemporary series of Cainsville stories, so naturally there are unforeseeable occult consequences for the characters in her tale. Brian Evenson’s “Sisters” is a mordantly funny look at Halloween through the eyes of two sisters who, as they prepare to go trick-or-treating to blend in with the kids in their new community, gradually reveal that their family is of the Addams sort, and that they have a comparably creepy perception of what represents “normal.” Halloween festivities overlap celebrations of the Mexican holiday Dia de Los Muertos, which Eric J. Guignard acknowledges in “A Kingdom of Sugar Skulls and Marigolds”, an exhilirating hiphop rhapsody to the memory of family and friends that reads like a woodcut of posturing Posada skeletons come to life. Among the book’s most novel stories is John R. Little’s “The First Lunar Halloween”, a Bradburyesque tale of the future in which the children of settlers on the moon attempt to replicate the traditions of the holiday as it was celebrated long ago on the earth, only to discover that the moon has more than its share of darkness to contribute to Halloween’s horrors.

Other selections are more conventional tales whose horrors are intensified by their Halloween settings. Seanan McGuire’s “With Graveyard Weeds and Wolfbane Seeds” concerns a group of kids who trespass in the local haunted house for a night of Halloween mischief and who suffer the grim fates that usually befall those who are too confident to be scared. Jonathan Maberry, in “A Small Taste of the Old Country”, convenes former Nazis in exile in Argentina for a Halloween feast where revenge against them is a foregone conclusion (although the form that it takes is not). S.P. Miskowski’s “We’re Never Inviting Amber Again” is a tale of a fortune-telling stunt gone bad at a Halloween get together, and Garth Nix’s “The Seventeen-Year Itch” is a tale of misguided professional arrogance in which a new administrator at a hospital for the criminally insane foolishly decides that it’s time to break the annual cycle of one notorious inmate’s imprisonment in a high-security cell every Halloween. These are stories whose Halloween trappings telegraph to the reader from the outset that the horrifying climax to which events seem to be building is inevitable. Interspersed among them are Paul Kane’s “The Turn”, which beguiles with its account of an imaginary boogeyman on the prowl on Halloween before deflty overturning reader expectations, and Stephen Graham Jones’s “Dirtmouth”, in which a grieving husband believes that his wife has returned from the dead one Halloween evening to console him, only to discover how badly he’s underestimated her true intentions.

The merits of all of the stories Datlow & Morton have selected notwithstanding, there are several standouts. Jeffrey Ford’s “Witch Hazel” is an account of a tradition supposedly followed by residents of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens of pinning a sprig of the witch hazel plant to their clothing during the Halloween season. It’s a horror story, to be sure, but Ford writes it as though it were a non-fiction feature piece for a mainstream publication, backing up its horrifying revelations with citations from the historical record and supposed eyewitness testimonies. It’s a wonderfully effective story that bears out Lovecraft’s observation that the best horror stories are those written like a hoax to convince readers of their authenticity. John Langan’s “Lost in the Dark”, the book’s longest story, is also concerned with matters of authenticity. It’s an account recorded on Halloween by a reporter named John Langan, who is interviewing the director of a cult horror movie entitled “Lost in the Dark” that was supposedly based on a strange-but-true event involving murders and a woman’s unexplained disappearance in upstate New York in the late 1960s. In the course of the interview the director reveals that she originally shot the film as a documentary but that its approach resonated more strongly with a film industry and audience with an insatiable appetite for true-seeming found-footage horror movies. The legend of “Bad Agatha” that the film elaborates has become much better known and more popularly believed than the unexplained true events on which it was based, blurring the boundaries between truth and fiction. Langan moves back and forth between the events that inspired their documentary treatment and how they were shaped into a horror movie (as well as into his fiction), setting up his narrative like a series of mirrors turned toward one another that make it impossible to tell which is the original source and which a reflection or distortion of it. It’s a marvelous bit of authorial magic that has as much to say about the creation of horror stories as it does about the popular culture in which those stories find traction. It’s a fitting cap to an anthology whose stories more often than not transcend the expectations for their Halloween theme.

Stefan Dziemianowicz, Contributing Editor, is author of The Annotated Guide to Unknown and Unknown Worlds and a collection of re-told urban legends, Bloody Mary and Other Tales for a Dark Night, and editor (with S.T. Joshi) of three-volume reference work Supernatural Literature of the World: An Encyclopedia and of more than thirty anthologies including Bram Stoker Award-winning Horrors: 365 Scary Stories, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, and 100 Ghastly Little Ghost Stories. Between 1991 and 1999, he edited critical magazine Necrofile: The Review of Horror Fiction. His critical work on horror and fantasy fiction has appeared in Washington Post Book World, Lovecraft Studies, and other publications, and he is a regular contributor to Publishers Weekly.

This review and more like it in the October 2017 issue of Locus.